Dillo through the Decades: Histories conflict on the evolution of the largest student-run music festival in the country

May 19, 2016

A&E

As students anticipate the arrival of artists such as ScHoolboy Q and The Mowgli’s to the Lakefill on Saturday, few likely stop to think about how Dillo Day became a trademark part of the Northwestern experience.

“There’s lots of lore around it,” said Mayfest spokeswoman Elisa O’Neal, a SESP senior. “There are really a lot of things that could totally be true, we just don’t know how they all tie together. … I don’t think a lot of Northwestern students really question it, and if they did they’d be like ‘why does this exist?’”

Although there is little definitive proof of how Dillo Day started, the story Mayfest tells is that a group of students from Texas gathered in 1972 to celebrate the armadillo, an iconic animal in their home state, said Mayfest spokesman Ben Bass, a Communication junior.

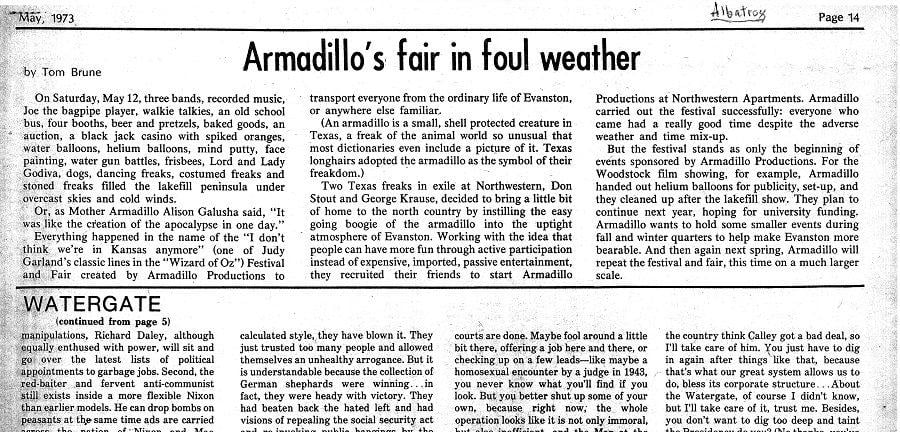

A memo from 1973 outlined the first annual “I Don’t Think We’re In Kansas Anymore” Festival and Fair presented by Armadillo Productions. The event was described as an afternoon on Deering Meadow in which student organizations would operate booths — from fortune telling to body painting — to have fun through active participation rather than expensive, passive entertainment.

Donald Stout (Weinberg ‘73), who said he founded what is now known as Dillo Day, said the event arose out of a desire to create a spring festival that wasn’t related to Spring Thing, an event geared toward members of Greek life.

“Our thinking was, ‘Hey, we don’t fit into that, it’s so dominated by the Greeks, let’s do something different,’” he said. ”And out of several nights of marijuana smoke-filled rooms, this idea arose.”

But another document provided a different origin story. In a memo from the University Archives, titled “Dillo Day: How It All Began,” Richard Gochnauer (McCormick ‘72), president of the 1971 Interfraternity Council, said IFC and the Panhellenic Association pooled their excess money to fund a school-wide party with five bands that would play all afternoon and into the night.

But in an 2005 email from Stout to a University archivist, Stout contended that the story about IFC funding was an inaccurate depiction of the founding of the annual tradition, and his non-Greek-affiliated festival is what developed into the modern version of Dillo Day.

Although Mayfest is now a student organization, it hasn’t always been. According to a 1980 article from The Daily, Mayfest was a several-day festival founded in 1977 as a combination of other springtime events. That year’s festival comprised 70 events over a period of 10 days.

Mary Recktenwalt (McCormick ‘84) said she remembers Armadillo Day — what it was called during her time at NU — as a school-wide event.

“If you hadn’t seen some of your friends in a while, then that would be the place to go ‘cause you knew that if you spent the whole day there you would run into people that you hadn’t seen in awhile so it was a big deal,” Recktenwalt said. “It was just a time for everybody to just kick back and relax and eat and listen to music and just kind of hang out.”

Today, although Mayfest still centers on Dillo Day, organizers said they try to put on diverse events that appeal to as many students as possible. O’Neal said many people only know Mayfest as the people who put on Dillo Day when in reality, they are responsible for putting on events from Battle of the DJs to Mayhem, a free student variety show held at World of Beer, 1601 Sherman Ave.

O’Neal said the various events have one common thread.

“We think music has a way of bringing people together so our events find a lot of different ways to do that,” she said.

The histories of Dillo Day and Mayfest are far from concrete, and there’s no question that they have evolved significantly over the years. For instance, 10 straight days of programming and a costume contest with a prize of a horseback ride across Deering Meadow are things of the past.

Stout said he is surprised that the festival has lasted more than four decades. Although no one he worked with intended for it to leave a long legacy, it makes sense that other students wanted to build off the success of his festival, Stout said.

“But maybe some group will decide, ‘We’re tired of this, we want something alternative’ and maybe something else will start,” he said. “That wouldn’t be a bad thing either. Things need to get disrupted once in awhile, that’s a good thing.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @kelleyczajka