Famed Northwestern macroeconomist Robert Gordon predicts end to life-changing innovation

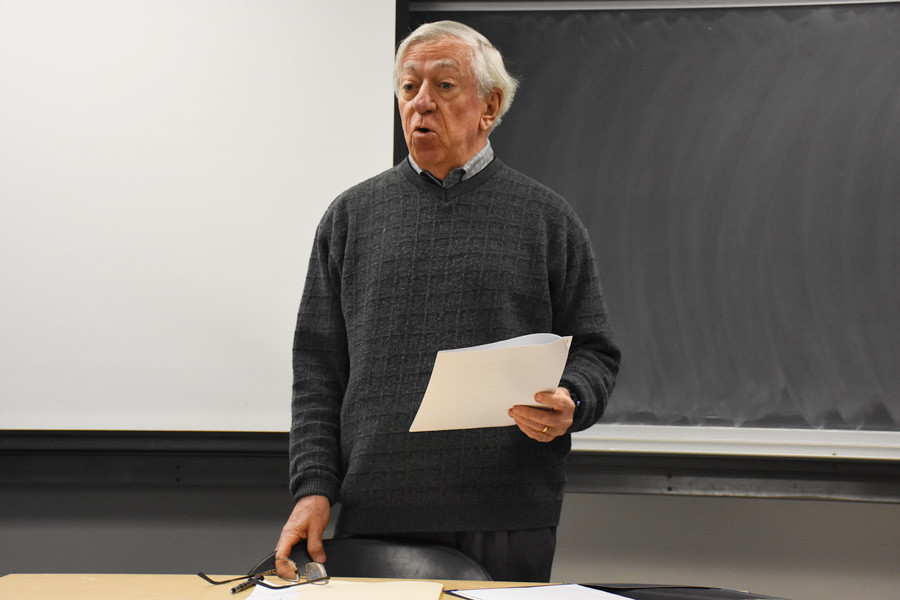

Sophie Mann/Daily Senior Staffer

Economics Prof. Robert Gordon addresses students in his “Did Economics Win Two World Wars?” class. Gordon’s book arguing America’s years of prolific innovation have passed, “The Rise and Fall of American Growth,” was published in January.

February 9, 2016

The gloomy economist sits in a large office that reveals no inkling of his pessimistic predictions. Glass awards rest on his desk, model airplanes decorate the shelves and original photographs from India line the walls.

But for economics Prof. Robert Gordon, these airplanes and photographs symbolize the fading glory of a past era.

“The outlines of most of the inventions that are going to change life are fairly clear now for the next 25 years,” he said. “I’m not saying innovation is over, what I see is that it’s incremental and slowly advancing along fewer dimensions of life than the great changes between 1870 and 1970.”

In his new book, “The Rise and Fall of American Growth,” published on Jan. 12, Gordon argues that years of prolific innovation have come and gone. Developments in technology following the Civil War, Gordon writes, far surpass the relatively insignificant achievements of recent years. Things like electric lighting and air travel transformed the nation and nearly doubled average life expectancy. Today, he said, society has neared an end to this great wave of invention, facing rising inequality, an aging population and crippling debt.

Many economists, including those within his department, disagree. Economics Prof. Joel Mokyr, who teaches economic history, said advances in quantum computing, genetic modification and 3D printing will radically change the world and boost productivity. These two fundamentally opposed views represent a notable schism in the field of economics, a debate over the future of the 21st century dating back to the Great Recession that began in 2007.

Gordon comes from an influential family of economists. His father served on the Brookings Institutions’ Panel on Economic Activity and his mother graduated with a doctorate in economics. But at first, Gordon’s varied interests seemed divergent from those of his parents.

Determined to become a TV director at age 16, Gordon met with the president of CBS and a famous producer. At the meeting, he received harsh news.

“The producer talked to me for a while and told me in no uncertain terms I had no business having any ambition to be a television director,” he said. “I’d never make it.”

Luckily, the intellectual had other interests. In high school, he played one of the leads, Colonel Purdy, in “The Teahouse of the August Moon,” a 1950s dramatic comedy, and served as editor of his school newspaper, the Berkeley High Jacket.

“He was very dynamic,” said long-time childhood friend Tim Laddish. “He capped his drama career with a performance in the senior play — the character was an older, opinionated curmudgeon and Bob really seemed to get into that.”

Laddish grew close to the jack-of-all trades when the two worked together on a weekly radio show for which Gordon served as pop music expert. The boys spent hours together producing short clips for an audience of unknown size. Pieces they broadcast were sharply humoristic and covered everything from local concerts to championship football games, Laddish said.

But academics were Gordon’s main pursuit, Laddish said, facing strong pressure at home to perform well and stay on top. And he did. Gordon graduated first in his high school class of about 600 students and went on to study at Harvard University.

The competitiveness of the Ivy League institution came as a shock to Gordon, who had grown accustomed to his top position in high school. Instead of continuing his former extracurricular activities, Gordon devoted himself entirely to academics.

“All of a sudden I was a small fish in a big pond,” he said. “It was more competitive and I had to work harder.”

Entering college, Gordon knew he wanted to become a professor, at first setting his sights on business due to a former interest in management consulting. But after a pivotal conversation with a professor his junior year, Gordon again changed paths and began to pursue economics.

While at Harvard, Gordon also met his future wife. She had been dating his sophomore roommate and when their relationship fell apart due to long distance woes, Gordon “stepped in.” The two went on a few dates, exchanged hundreds of love letters and spent a “prim and proper” summer together at his home in Berkeley, California, after which Gordon proposed.

From then on, life turned out exactly how he planned it, Gordon said. After Harvard he attended Oxford University, receiving top honors and went on to earn a doctorate in economics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

At age 75, the multi-talented economist’s experiences as a former actor, newspaperman and radio broadcaster serve him well. He enjoys watching movies, reading history textbooks and teaches undergraduate first-year seminars.

“(Gordon) very early on figured out what he likes,” said economics Prof. Mark Witte, director of undergraduate economics studies. “He plans his life carefully, when he’s going to work, where he’s going to eat and where he’s going to go for trips. He thinks about productivity a lot and he clearly embodies that in his life.”

Economics Prof. Martin Eichenbaum characterized Gordon as a man of two minds who could be both charming and tough, rarely backing down from an opinion. At the same time, Eichenbaum said, the two have shared many warm dinners and thoughtful conversations.

All of his colleagues, however, agreed that Gordon’s contributions to the field of economics have been transformative.

“It’s magnificent that somebody like Bob Gordon maintains this professional cutting edge to this day,” Laddish said. “He can inspire a lot of people of our age group to realize that you don’t have to sit back and just watch television.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @davidpkfishman