Living in Red: Slavic Prof. Irwin Weil ties love for Russian culture with longtime passion for performance

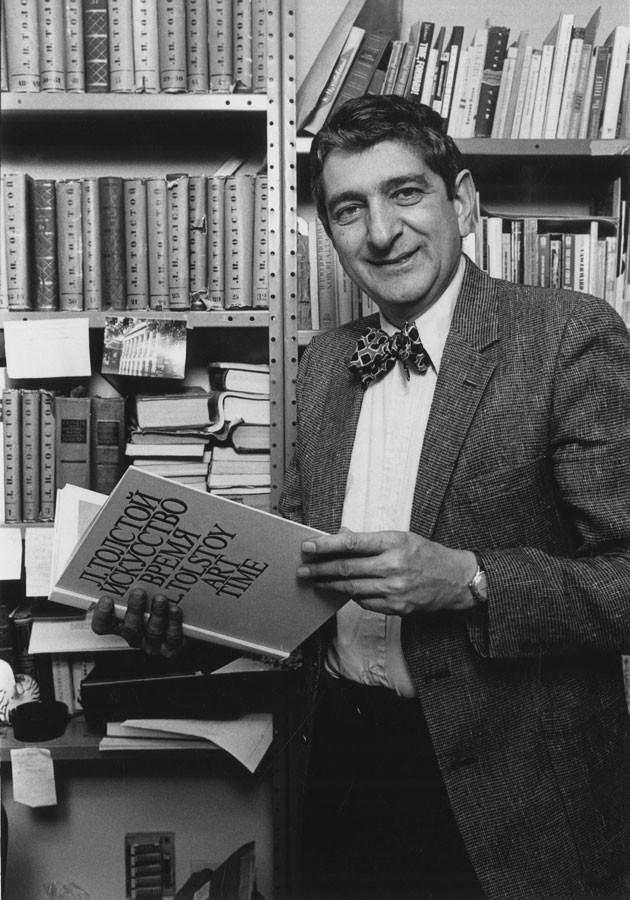

Prof. Irwin Weil holds a book about the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy in his office. Weil has been teaching at Northwestern in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures for almost 50 years.

November 12, 2015

A&E

Heart pounding, blood rushing, he stands center stage in the Novosibirsk Theatre, Russia’s largest opera house. Velvet seats and gold-embossed sculptures line the hall. A statue of Vladimir Lenin stands outside. Taking a deep breath, he begins to sing.

Born in Cincinnati, Prof. Irwin Weil has been singing for most of his life. It is the thread that connects his main interests, from childhood experiences with Major League Baseball to teaching about Soviet Russia. In May, he published a book of memoirs titled “From the Cincinnati Reds to the Moscow Reds,” which presents snapshots of his life.

Among the book’s stories are details from his nearly 50 years of teaching Slavic languages at Northwestern. During that timespan, he has taught thousands of students.

“Weil lit the fire in my passion for all things Russian,” said Ian Kelly (Weinberg ’79), who serves as the U.S. ambassador to Georgia. “Everyone who’s had Irv remembers the twinkle in his eye, the bowtie and his declamatory style of lecturing.”

Shakespeare and the Cincinnati Reds

From the start, Weil had an affinity for the stage. As a young boy, he learned to sing a cappella in the local synagogue choir, he said. In high school he played Prospero in Shakespeare’s “The Tempest.” He was elected boy-mayor of Cincinnati — a role he dutifully filled for a day.

“He was the opposite of shy when it came to performing,” said Howard Schuman, a childhood friend. “And he had a voice that went with it.”

Although Weil believed himself destined for the opera, he said he spent much of his time following America’s greatest pastime: baseball. But Weil, whose father owned the Cincinnati Reds, wasn’t just catching fly balls on the Little League field, he was brushing elbows with legends.

He attended game after game, meeting icons like Branch Rickey, who broke the color barrier in the MLB. For Weil, it wasn’t the sport that captivated him so much as the experiences that came with it.

“Every game I had a running bet with my aunts,” he said. “If Ernie Lombardi got a hit, they would get me a chocolate ice cream soda. He usually got a hit.”

From Dostoevsky to the KGB

By the time Weil was 18, he had already studied works from the Bible to Shakespeare, and considered himself a scholar of prose. But neither God nor the famous English poet could compare to Russian literature.

“I was a freshman at the University of Chicago and they had us read a book by Dostoevsky,” he said. “It knocked me for an absolute loop.”

It was through literature that Weil became infatuated with Russian culture, eventually receiving a master’s degree from the University of Chicago in Slavic studies.

After college, Weil worked at the U.S. Library of Congress helping a demographer form a census of USSR casualties in World War II. He had long dreamt of visiting the Soviet Union and finally got the chance in 1960.

“I got off the plane and what really surprised me was the enormously warm hospitality,” he said. “Especially when they knew I was American. To my amazement, they couldn’t do enough for me.”

While there, Weil immersed himself in the country’s opera scene, attending concerts and discussing Russian music in the native tongue.

Once, at an opera performance in former Leningrad, Weil was confronted by a Russian who asked if he was a Jew. The two started talking, and he requested Weil come meet his father.

When Weil arrived at the house, the man handed him a dusty book detailing the names of family members killed by the Nazis. Weil was speechless. The three men sat sipping warm tea with varenya, a jelly Russians use to sweeten their drinks.

“Kol yisrael chaverim,” Weil said. “All Jews are brothers.”

Matters of life and death

Today, Weil teaches a class on Russian culture with Bienen Prof. Natalia Lyashenko, melding literature and music. At the end of the quarter, his students sing opera for an open audience in the Alice Millar Chapel.

Weil, who will be 88 next year, said he has only one regret: not joining the professional opera.

“Boy if I could be Chaliapin or Hvorostovsky, wow,” he said, referencing well known Russian opera singers. “I’d be on top of the world.”

On the Jewish High Holy Days, Weil co-leads Fiedler Hillel services with a younger cantor. He handles the contemporary, she the modern. It is a duty he would rather die than give up, he said.

But death doesn’t cross Weil’s mind very often, he said.

“Of all things that men fear, the strangest thing to me is death,” Weil said, quoting Shakespeare. “Seeing that death, a necessary end, will come when it will come. Cowards die many times before their deaths. The valiant never taste of death but once.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @davidpkfishman