Egyptian protester discusses social media’s role in revolution

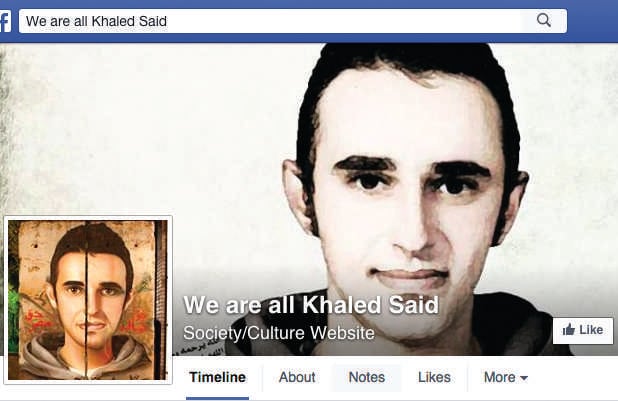

Wael Ghonim created a Facebook page that played a major role in organizing citizens during the Egyptian Revolution. “We are all Khaled Said” received 100,000 “likes” in three days.

April 14, 2015

Wael Ghonim doesn’t like to call himself an activist.

However, the Facebook page he created to protest the Egyptian government and its leader Hosni Mubarak after a young Egyptian man was killed by police in 2010 played a major role in starting the country’s revolution.

“I am not an activist,” Ghonim told more than 100 Northwestern students and faculty members Monday afternoon. “I don’t see myself that way, and I didn’t see myself that way in those days. I see myself as a concerned citizen.”

Ghonim, a former Google marketing manager for the Middle East and North Africa, discussed his experience using social media and the Internet to organize and inform citizens. Currently a resident of Palo Alto, California, Ghonim was present in Cairo, his birthplace, during the revolutions in 2011.

Despite his rise to becoming a well-known figure during the revolution, Ghonim reiterated how much he disliked labeling himself the face of the revolution. He did not see himself as an “activist” who spent considerable time researching literature on social issues, he said. Still, he didn’t balk at putting himself at risk, as he flew to Cairo at the start of the protests.

The page he created, “We are all Khaled Said,” was named after the young man killed by the police after attempting to expose police corruption. Ghonim said Said’s profile as a normal, middle class man, allowed regular citizens to relate to the movement.

“The page became a platform for creating awareness, to see police brutality in Egypt,” Ghonim said, adding that Egypt before the revolution was divided. “We are living in two Egypts. The upper middle class are living their own lives, they don’t care too much about the police brutality that happens every day, some of them will even tell you ‘this is the only way these people can be governed.’ We needed to see how we could get their attention.”

The page garnered more than 100,000 “likes” in three days, Ghonim said, and grew even more after he created a Facebook event calling for protests in Tahrir Square.

A few days after the protests, Ghonim was detained by Egyptian authorities and unable to monitor the ensuing national unrest in the country. Eleven days later, he was released and gave an emotional televised speech about the protesters who died while he was detained.

Ghonim said the mobilization that led to the revolution was successful due largely to the collective ownership participants felt for the movement.

“Muslims and Christians, Islamists and liberals, communists and leftists, groups from different economic standpoints were living in euphoria,” he said. “They were all dreaming of a different Egypt. What was happening was a collective ‘Let’s get rid of Mubarak.’”

Medill graduate student Aditya Prakash said he was impressed with Ghonim’s talk, but differed slightly on Ghonim’s rationale behind being a proponent of democracy while supporting Mohamed Morsi as a candidate for the Muslim Brotherhood in 2012.

“The question was asked, ‘How can you reconcile yourself with voting for the Muslim Brotherhood with regard to its history,” Prakash said. “If you look at the guy that founded the Muslim Brotherhood, he is considered the father of radical Islamists today, and with (Ghonim) being a liberal and supporting them temporarily, I think this is an explorable dichotomy.”

Ghonim concluded his speech with a preview of a new social media venture called “Parlio,” a meritocratic variation on Facebook. The website’s algorithm will sort the importance of content based on experts that “like” or comment on posts rather than by the number of “likes” a post receives, as Facebook currently functions.

McCormick Prof. Michael Marasco, director of the Farley Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation, encouraged his students to attend Ghonim’s lecture.

“This was a perfect example of the power of technology and the utilization of social media as a tool to mobilize people that share different views,” Marasco said.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @elenasucharetza