Retired Georgetown professor gives lecture on WWII ‘comfort women’

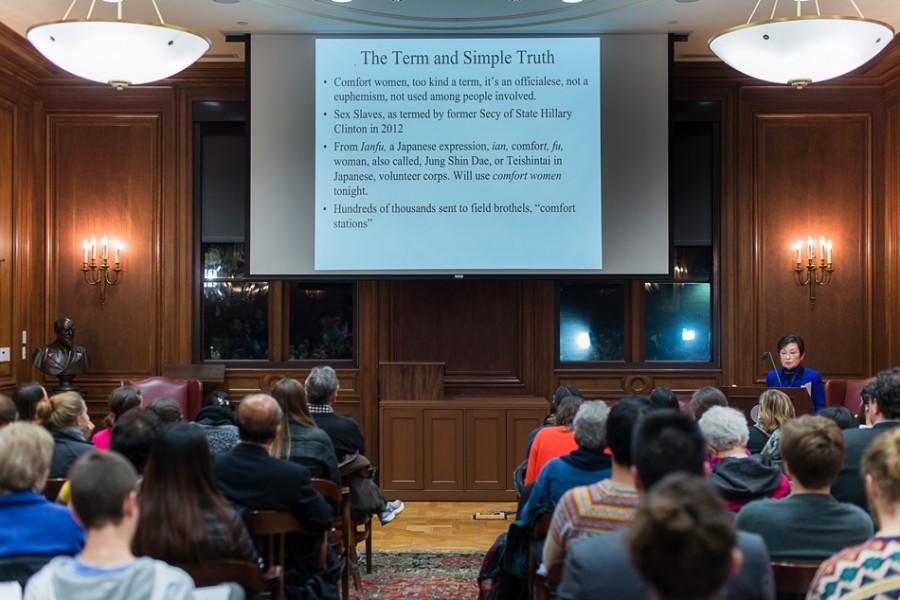

Bonnie Oh, a retired Korean studies professor from Georgetown University, speaks in Harris Hall about “comfort women,” sex slaves who were forced to serve Japanese soldiers during World War II. Oh spoke to a crowded room in a lecture held by the Buffett Center.

November 13, 2014

A retired professor of Korean studies spoke to a packed room in Harris Hall on Wednesday night about “comfort women” who were enslaved for sex by the Japanese army during World War II.

Bonnie Oh, a retired Georgetown University professor, recounted the history and legacy of an estimated 80,000 to 400,000 women and girls who were forced into sexual slavery for the Japanese army from 1931 to 1945. She said during the war, the women gathered at “comfort stations” near military bases.

“Soldiers would queue up, assigned to certain times,” Oh said in a lecture hosted by the Buffett Center. “Sometimes when there were new shipments of soldiers, these times would be no longer than 15 minutes, with no time for the women to wash up in between.”

Although these women came from all over Asia, 80 percent of the victims were Korean, because they were believed to be more likely free of disease, Oh said. Because of her concentration in Korean studies, Oh became interested in these women, though she said her peers did not approve of her interest.

“When I first started getting interested in this topic 22 years ago, I was almost ostracized — a good woman getting interested in a topic like that,” Oh said.

The topic of comfort women was new to some attendees, including Weinberg sophomore Sanjana Lakshmi, who attended a dinner with Oh before the presentation. Other members of the International Gender Equality Movement, a student group that promotes advancing women’s rights worldwide, also attended the dinner.

“I knew there was rape and pillaging and other war crimes during World War II, and I know there’s sex trafficking, but I didn’t know there was this systematic sex slavery,” Lakshmi said.

The Japanese government has tried to avoid the topic of comfort women, particularly when it comes to the government’s culpability in their enslavement, Oh said.

“The repeated claim is that the Japanese government was not involved, that these women were professional prostitutes,” Oh said.

The only remaining records of the exploitation are personal accounts and those of Japanese soldiers, since all other documents and evidence were destroyed after the war, and some of the women were killed.

Oh said the existing accounts point to the Japanese government’s culpability in setting up the system of comfort stations.

“Every country has ugly chapters which people would like to forget, but for which reparations are called for,” Oh said. “What is unique about comfort women in Japan is the official nature — the commanders in the field set up and regulated this system, and they had a direct line of communication with the emperor.”

Although the sex slavery system ended with World War II, the issue resonates with others struggling with sexual violence against women today, said Youngju Ji, the executive director of Korean American Women in Need, an organization for domestic violence and sexual assault victims in Korean and other Asian communities.

“It’s very much connected to what we are trying to do with our mission of ending violence against women,” Ji, who attended the event, said. “It was great for us to expand our knowledge about this issue going forward, to be more equipped with a different perspective on this issue.”

Oh said the impact the women’s stories can have upon others is essential to their legacy.

“There is a question of what kind of legacy these women can leave,” she said. “They are destitute, old and have nothing left to leave. But comfort women ended up leaving a lot of legacies in the lessons they gave us on human endurance and the strength to triumph and to survive.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @MadelineFox14