Fifty-nine thousand, three hundred eighty nine dollars.

That’s what undergraduate students pay annually to attend Northwestern, including tuition, student fees and room and board. With next year’s increase, that amount will surpass $60,000.

In 2012, the median household income in the United States was $51,371 and falling, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, meaning that for the average American family, the cost of sending a child to NU for one year exceeds its total annual income. It’s a staggering amount of money by any standard, but it is not an uncommon price tag among elite private universities. Combined costs at schools like the University of Chicago, Duke University, the University of Pennsylvania and Vanderbilt University ranged this year from $57,000 to more than $61,000.

“Knowing friends who go to universities of the same caliber, it’s not abnormal or unusual,” Medill freshman Mia Hariz said. “But it’s a lot of money. I do think it’s too expensive.”

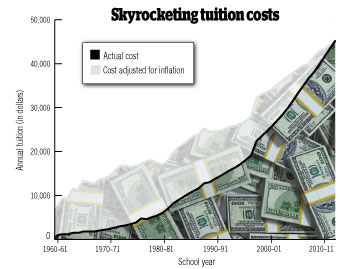

The College Board reported last month that private universities increased tuition and fees by an average of 3.8 percent in 2013 — the lowest rate of increase in more than a decade. But although costs are rising at a slower pace, they are still growing more quickly than inflation and much more rapidly than the median household income, which has stagnated in recent years.

NU continues raising tuition to stay competitive with other top research universities, but administrators say they try to keep in mind the possible impact expenditure increases will have on students.

“We have a real sensitivity to try to keep the tuition increase as low as we can,” said James Hurley, associate vice president of budget and planning.

But the skyrocketing cost has caused students like Weinberg sophomore Thelma Godslaw to question where tuition dollars are actually going and whether the University is spending more than it should be.

“I wonder who allocates the funds. How much extra do they have to blow at random things? Like we’re getting a new Norris,” she said of plans to build a new student center. “Do we really need to be spending money on that?

“Don’t get me wrong, we do get some pretty cool perks for going here. But it’s a lot of money. I know I couldn’t afford it without scholarships.”

On the rise

In 1960, attending NU cost just $960. Adjusted for inflation, that figure is about $7,600 in today’s dollars. But the University’s annual expenditures were also much lower back then: The cost to run the school was $33.4 million, or about $264 million today.

Today, NU costs nearly $2 billion to operate annually, according to the Office of Budget and Planning’s expense report for the 2014 fiscal year. That includes faculty and staff salaries, maintenance and utilities, employee benefits and capital projects, which can range from fixing a residence hall’s leaky roof to allocating money to construct a new building.

As a private university, NU does not receive any state or federal funding aside from grants. Instead, that $2 billion in expenses is covered by revenue sources like tuition, endowment payout and fundraising and gifts from donors. Other sources of income include sales and services such as room and board, television rights for football games and parking. Once financial aid has been factored in, tuition only accounts for about a quarter of NU’s total revenue.

“We’re not that dependent on net tuition revenue,” University President Morton Schapiro told The Daily in an interview last week. “We have a remarkably diversified revenue stream.”

Schapiro, who has a Ph.D. in economics, is a prominent scholar on the economics of higher education and has written many articles regarding tuition costs and financial aid.

“He brings a lot of expertise to the table,” Hurley said.

In the last 10 years, tuition has increased by 59 percent, jumping from $28,404 in 2003 to $45,120 in 2013. With tuition serving as NU’s largest source of unrestricted income, annual hikes have been necessary to keep up with the University’s burgeoning expenditures, which have gone up 85 percent in the last decade — and that’s not even including the cost of providing financial aid.

Ronald Ehrenberg, director of the Cornell Higher Education Research Institute, said rising expenses at NU are part of a larger trend of elite private universities spending more money to stay competitive with one another.

“The analogy I like to use is that of the Cookie Monster,” he said. “He tries to find as many cookies as he can and stuff them in his mouth. These great private research universities, they only have one goal, and that is to do the best they can in every dimension of their activities … and that costs money.”

To maintain their position at the top of the academic food chain, schools are pouring more money into research, facilities, financial aid and faculty salaries. Annual college rankings lists contribute to the sense of competition by stacking schools up against one another yearly, comparing them on everything from class size to research opportunities.

The U.S. News & World Report not only uses faculty compensation to determine the quality of professors but also factors in the amount of expenditures per student. Schools that spend more money, therefore, are generally ranked higher, the result being that universities must continue spending to remain competitive.

“It’s expensive, but the way I see it, it’s like paying for a name brand,” Medill sophomore Jillian Sellers said. “That name goes a really long way.”

A financial puzzle

As expenditures escalate, NU must raise revenue to meet spending needs. However, of NU’s various sources of income, some, such as gifts and grants, cannot simply be increased at the University’s discretion.

“It’s like a puzzle,” said Eugene Sunshine, NU’s senior vice president for business and finance. “You’re trying to match your needy expenditures against what you think you’re going to have in revenues for all the sources, recognizing that not all the sources can be spent on anything. Some of it’s specified.”

Research grants, for example, can only be spent on expenses directly related to that research. Gifts from donors, particularly endowment donations, are also often designated for specific purposes. So when the cost of employee benefits or student financial need increases, tuition dollars are the most flexible source of income NU has to pay for those expenditures.

This academic year, financial need increased about 6 percent from the previous year. Although the endowment and federal grants cover for some of that, NU primarily pays for additional financial aid expenses with tuition hikes.

“When the economy stinks and we’re concerned our students are going to be more needy financially than they might have been before, we need to be prepared to have more money for financial aid, because that’s what we do here: We accept you and then we meet your need,” Sunshine said.

Schapiro said NU has invested much more money in financial aid in recent years as part of the University’s commitment to actually meeting full need in its admissions process, rather than simply being need-blind.

“If you can afford to be need-blind and meet full need with modest loans, and you don’t do it, you did something that’s wrong,” he said.

However, expanding financial need presents a challenge because it is growing at a faster rate than the University is able to increase tuition. While financial aid increased 6 percent, tuition went up by only 4 percent last year.

“That gap is very likely to continue with our ability to increase tuition decreasing just because of the marketplace and how others will be behaving and what parent and student expectations are,” Hurley said. “It’s a constant tension to figure out what’s right.”

When tuition increases faster than median family income, each spike leads to more students needing more financial aid. With family income not currently increasing, this means the pool of students who qualify for aid only grows larger with each tuition raise.

“Unless we can hold tuition down below the rate of growth of family income, an increasingly smaller and smaller share of students will be paying full tuition,” Ehrenberg said.

‘Rich as hell’

In theory, tuition hikes could be avoided by instead increasing the amount of the endowment paid out each year.

In 2012, the University boasted an endowment of more than $7 billion, making NU among the top 10 richest universities in North America, according to the National Association of College and University Business Officers and Commonfund Institute. The endowment has since grown to about $8.7 billion, said Will McLean, NU’s chief investment officer.

“The endowment’s huge, it’s very large, it’s very impressive,” Sunshine said. “Some people say, ‘You’re rich as hell, you’ve got an $8 billion endowment.’ And that’s a lot of money, but we also have a budget each year of $2 billion. In simple terms, if you have an $8 billion endowment and a $2 billion budget, that’s four years.”

The endowment consists of a large pool of donations invested in various stocks and bonds, the intent being that it increases in value over time and serves as a lasting source of income for the University. Some donations are made with a specific object in mind, like supporting a student organization or academic department. Those portions of the endowment, and any earnings they might accrue, are restricted to funding those designated purposes.

“It’s all over the place,” Sunshine said. “People give money to support research in chemistry, they give it to support the professor’s salary who teaches writing. Usually the larger the gifts, the more explicit people are because they have a pretty good idea of what they want the money to go for.”

Paid out every year at a rate typically between 4.5 and 5 percent, the endowment is determined by the Board of Trustees based on recommendations from the Planning and Budget Group, which includes Sunshine, Hurley and Schapiro, as well as the provost and other administrators.

At its current payout rate, the endowment makes up 17.6 percent of NU’s total income. When NU’s various expenses rise, those additional costs technically could be covered by increasing how much of the endowment is paid out each year instead of increasing tuition.

However, financial markets are often unpredictable, and when the budget committee makes its payout rate recommendations each year, fluctuating rates of returns on investments are taken into account.

“You need to have some degree of predictability and stability,” Sunshine said. “If we make 18 percent a year on all our earnings, we’re not going to pay out to the schools and the University the full 18 percent of those earnings, because next year it might be negative 5 percent because the stock market goes down.”

If the payout rate is too high, the University runs the risk of damaging the earnings power of the endowment in the long run.

“The endowment is supposed to provide resources not only for the current generation of students but also for future generations of students,” Ehrenberg said. “If we were to force universities to spend more of their endowments than they want, that would benefit students in the short run, but the future generation of students would have less resources directed to them.”

Defining expenditures

Tuition hikes, financial aid expenses and the endowment payout rate are all considered when NU determines how much money it will spend each year and what it will be spent on.

The Office of Budget and Planning determines NU’s operating budget annually in coordination with the Planning and Budget Group. It is a multi-step, year-long process that determines expenditures and how much revenue the school must raise to meet expenses.

Much of the budget is committed to fixed or inflexible expenses, like utilities and contracts with vendors. More than $1 billion goes toward costs like staff and faculty salaries and employee benefits.

“We’re very people-centric in terms of where we spend our money, so unless you’re going to change that dramatically from one year to the next, a big chunk of the budget is already committed to my salary and other salaries and whatever salary increases we might be able to afford,” Sunshine said.

Once those expenses are factored in, the committee can consider new investments, Hurley said. NU’s deans and vice presidents meet with the Office of Budget and Planning beginning in the fall to propose new projects and campaign for additional funding.

“If we’re going to invest, tell us what you’re going to do — how are you going to stretch yourself?” Hurley said. “So it’s not all give me, give, give me. It’s how can we figure out how to get this done together.”

Recent budget priorities include large construction projects, such as the new music and communication building currently being built on South Campus, as well as what Hurley refers to as “non-sexy capital projects” like repairs and maintenance to older buildings.

A student voice

To give students input in money allocation, members of the Undergraduate Budget Priorities Committee work throughout the academic year to determine changes their peers would like to see on campus.

The group, which consists of eight committee members and the Associated Student Government president, serves as an independent student voice within the budgeting process. Though the president sits on the committee, the UBPC is not part of ASG, instead functioning as its own separate entity.

Each fall, the UBPC releases an online submission form called Campus Brainstorm asking students what they would change at NU if they had unlimited funds. At the end of Fall Quarter, they release a survey allowing students to vote on the aspects of undergraduate life they believe most need improvement.

“Students engage in our process in a really good way,” UBPC chair Chase Eck said. “Ours is the only survey that’s sent out to the entire student body.”

The UBPC then presents the survey results to the Planning and Budget Group and issues funding proposals for new projects based on what their research has shown to be a priority among undergraduate students.

Previous UBPC initiatives have included A&O Blowout, longer hours at the library and improved Wi-Fi coverage on campus.

“Their research is very good,” Hurley said. “By the time they get to the planning and budget committee it’s a very thoughtful, well-done presentation.”

Though only a limited amount of money is available to fund UBPC proposals — that same pool of money that’s left over after salaries, maintenance, financial aid and other fixed costs have been accounted for — Eck said he believes the committee informs administrators about student needs they would not be aware of otherwise.

“Just getting in front of the administration and talking to them about these issues helps start conversations they might not be having otherwise,” the Weinberg senior said.

‘Worth it’

With the Office of Budget and Planning meeting with representatives from NU’s schools and departments, preparations for the 2015 fiscal year are already underway.

The UPBC is also readying its annual survey, and discussions with the Board of Trustees regarding next year’s tuition increase and endowment payout rate begin this month.

Alhough the exact amount of tuition increase will not be known until March, the total cost of attending NU, including fees and room and board, will surpass $60,000. How much costs will continue to increase in future years and whether elite private universities like NU will be able to cut back on expenditures to temper tuition costs remains to be seen.

Although students are concerned about the sustained tuition increases, some say an NU education has long-term value.

“In the grand scheme of things, it’s reasonable,” Sellers said. “The opportunities you get from going here … I think it’s worth it.”

Email: amywhyte2015@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @amykwhyte