University President Morton Schapiro does not always know what he is going to say.

Before Schapiro’s first speech as president of Williams College in 2000, the school’s presidential search committee chairman asked about his planned remarks. Ray Henze got an “I don’t know” from Schapiro in response.

“I thought, ‘Oh my goodness, he doesn’t even have notes,’” Henze said.

Schapiro continued that unconventional style at Northwestern after moving on from Williams. He is known for his unguarded personality, and his leadership is characterized by unscripted speeches and conversations. His relentless energy, seemingly endless supply of purple sweaters and insistence that people call him “Morty” have all colored his presidency over the past four years.

Those colloquial quirks mostly work in Schapiro’s favor.

“Morty definitely has his own style, and he is irreverent and off-the-cuff at times,” said Burgwell Howard, assistant vice president for student engagement. “Some presidents are more reserved and are more concerned about, ‘Oh my gosh, how is this going to sound?’ Morty is genuine.”

However, Schapiro’s frankness can come off as undiplomatic at times — especially during controversies. As he prepares this month to graduate his first freshman class, Schapiro’s unorthodox style has defined his tenure at NU, which has been marked by both success and controversy. Schapiro will remain president for at least the next five academic years, and though he enjoys celebrity status on campus and champions the undergraduate experience, some wish he would take a stronger stance on important student issues.

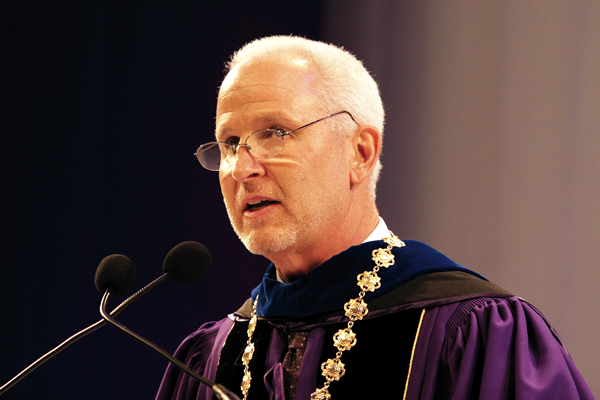

Schapiro speaks at his presidential inauguration. In his speech, he emphasized the importance of finding Northwestern’s place in the broader world. (Daily file photo)

The jet-setting president

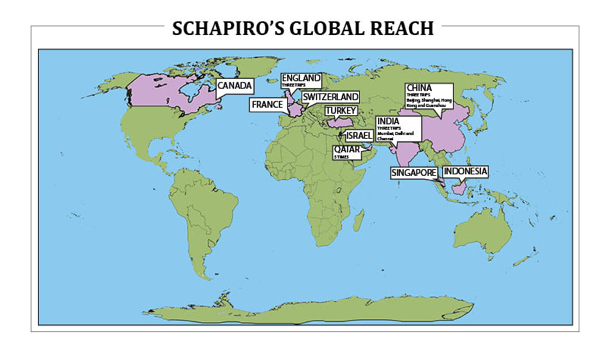

On his way back from a trip to Indonesia last month, Schapiro calculated that he spent seven months abroad in the last four years, making 21 trips to 11 countries since 2009.

His relentless travel schedule includes fundraising meetings, alumni events and speaking engagements. He has most frequently gone to Doha, Qatar, visiting NU’s satellite campus five times. He has also made three trips each to China, India and Great Britain. Other destinations include Turkey, Israel and Singapore.

Infographic by Rebecca Savransky (click to expand)

The president often flies to cities like New York, San Francisco and Boston, which have many NU alumni and donors. He also regularly visits Springfield, Ill., and Washington, D.C., meeting with politicians about issues ranging from research funding to gun control reform.

Despite his exhaustive schedule, Schapiro tries to remain present on campus and accessible to undergraduate students. He attends as many sporting events, student productions and fireside discussions as he can, he said.

“When you’re gone 70 out of 120 days, you better make sure the 50 days you’re on campus you get to see a lot of students and faculty and staff,” he said.

Purple pride

Schapiro is adored by students at NU and Williams, where he served as president for almost a decade. Students at both schools say they feel at ease around him.

“Just the fact that people call him ‘Morty’ and not ‘President Schapiro’ tells you what people think of him,” said Pei-Ru Ko, who graduated from Williams in 2009 and played an active role in the college’s student council.

Schapiro’s easygoing disposition has even made him a topic of conversation online. He periodically appears in students’ Facebook profile pictures, and his speeches have even been spliced together for song parodies like Taylor Swift’s “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together.”

Other students admire Schapiro for his love of sports. He regularly attends football games; students almost always chant “Morty! Morty!” upon his arrival on the NU sideline.

Schapiro watches a Northwestern football game. The athletic department has surged in recent years, coinciding with increased focus on athletics from the administration. (Daily file photo)

“Students notice,” said Williams Provost Will Dudley, who has known Schapiro since the 1980s. “They see the short guy with gray hair in the purple sweater sitting in the front row. They know he’s there.”

Schapiro is also known to host dinners at his house, a tradition he started at Williams. He and his wife, Mimi Schapiro, often invite students to take home desserts to their friends as their two Labradoodles, Millie and Lambchop, scurry underfoot.

Nearly 2,500 people dine in their home each year, Mimi Schapiro said, noting that she hosts about two to three dinners per week.

“It’s a great way for (students) to see how we live, too, but also for Mort to meet them out of the classroom, out of the campus, in our home,” she said.

Students say they appreciate Schapiro’s efforts to personally connect.

“He reminds me a of a high school principal who’s really involved and … cares about the student body,” said Weinberg sophomore Pamela Wax, who took Schapiro’s humanities class last quarter.

Schapiro interacts with students during a Political Union event. Schapiro says he tries to attend as many student events on campus as he can. (Daily file photo by Jenna Zitaner)

Containing controversy

Despite Schapiro’s popularity, students say he is not so candid when it comes to controversial topics.

This year, the University’s disassociation from Tannenbaum Chabad House and Rabbi Dov Hillel Klein was met by fervent student backlash.

NU cut ties with Chabad because the organization served alcohol to student at Shabbat dinners. Students are carded for events at Schapiro’s house, but he admitted he was unsure about the procedure for wine at his Passover dinners.

Matt Renick, former president of the Chabad House student executive board, said the administration did a “terrible job” handling the disaffiliation, which he said happened with a “lack of transparency.”

“It was his job first and foremost at the very least to hold off on that decision … and come up with some level of understanding,” the Communication senior said.

From early 2010 until September 2011, Schapiro clashed with students of the Living Wage Campaign seeking to raise NU employees’ salaries. Schapiro disagreed with students about the economics behind their cause, asserting that raising wages would lead to layoffs.

Weinberg senior Will Bloom, an active participant in the campaign, said Schapiro could better engage students and “lead a more democratic university.”

“He does play the politics game of being kind of wishy-washy,” Bloom said. “I wish he was more of a good-faith participant in actual discussion making.”

Students protest to raise workers’ wages during the Living Wage Campaign. Schapiro butted heads with students over the economics behind the cause.

This quarter, student activists worried that his refusal to sign or answer petitions indicates a lack of concern about student causes.

“How do you not listen to the students?” asked Weinberg sophomore Heather Menefee, co-president of the Native American and Indigenous Student Alliance.

Schapiro called handling tough issues a constant work in progress, saying that the University can “always do a better job” by learning from past experiences.

“Sure, everybody loves Morty, but does everybody love what Morty does?” Renick said. “The answer is clearly no.”

Diversity: A constant concern

Issues surrounding diversity and inclusion have trailed Schapiro since his years at Williams, with events at both schools closely mirroring each other.

Toward the end of his tenure at Williams in January 2008, classes were suspended after racial epithets and obscene drawings were scrawled on several students’ dorm doors. The incident triggered a student and faculty movement of collective meetings, forums and an all-school rally.

The movement spawned the now annual “Claiming Williams Day,” when classes are canceled in lieu of community discussions, forums and performances focusing on diversity and inclusion.

Morgan Goodwin, former co-president of the Williams student government, said he wished Schapiro had been more personally involved during the dialogues. Kim Dacres, the other co-president, said some students wanted a stronger condemnation from Schapiro.

“Some of the things were so deeply personal — you want to feel like the institution, the school at large, is on our side,” Dacres said. “That starts with the face of the school.”

Schapiro participates in a February 2012 panel on campus diversity issues. Some students were critical of his body language, saying it was indicative of his lack of commitment to the issue. (Daily file photo by Rafi Letzter)

One year later, Schapiro confronted racially biased incidents again, this time at NU. Just three weeks after his inauguration in October 2009, two students wore blackface for Halloween, sparking a series of community forums similar to those at Williams.

NU’s diversity movement intensified last year when three more culturally insensitive incidents occurred in succession. Calls to address diversity culminated in a rally at The Rock at the end of last quarter after a black bear was found “lynched” above a maintenance worker’s desk.

By university metrics, Schapiro’s administration has responded quickly to diversity issues. Over the last year, NU instituted the University Diversity Council, added three diversity-focused administrators and formed the Bias Incident Response Team.

But some students say those “Band-Aid efforts” and Schapiro’s engagement only occur on a superficial level. SESP senior Kerease Epps, former president of Minorities in the Pursuit of Law, said she wishes the president’s approach was more hands-on and transparent.

“His stance resonates throughout the campus,” said Epps, who also served on the executive board of For Members Only for three years. “If he presents himself as a firm stance, then others will actually follow in his footsteps and learn to take the issue more serious.”

From economics to executive leadership

As a preeminent economist, Schapiro never aimed to become the president of an elite university.

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in economics from Hofstra University and receiving his doctorate at the University of Pennsylvania, Schapiro became a faculty member at Williams, where he taught economics and gained national recognition for his work on enrollment access and the economics of higher education.

Schapiro spent nine years at the University of Southern California, first as the chair of the economics department and later as a dean and vice president for planning. Schapiro said he then “fell into” his first presidency after conversations with Henze, returning to Williams in 2000.

Schapiro became NU’s 16th president in 2009. He is one of the top 20 highest-paid college presidents, taking home $1.25 million in 2010. He also sits on the board of Marsh & McLennan Companies, a global consulting and risk management firm.

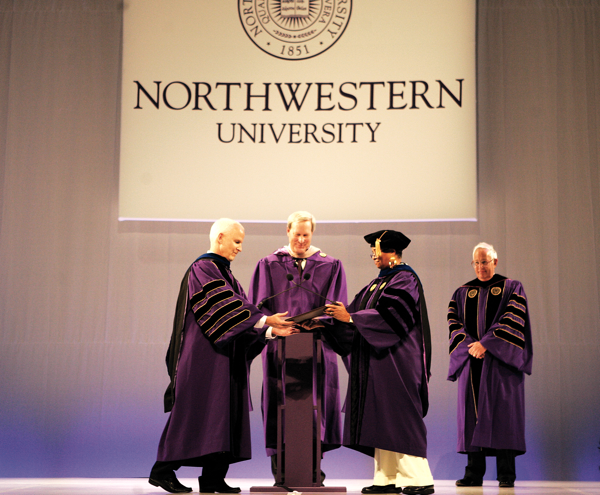

Schapiro is inaugurated as NU’s 16th president on Oct. 9, 2009. He replaced Henry Bienen, who served for more than 14 years. (Daily file photo)

He now oversees 16,000 students and 10,000 staff and faculty members, as well as a $1.91 billion operating budget.

“I love being president,” Schapiro said. “It’s intellectually challenging and rewarding, but I didn’t go to school to become a president. I went to school to become an economics professor — a job I very proudly hold.”

Unconventional approach, conventional success

“Professor” always follows “president” in Schapiro’s email signatures, a balance many college presidents are unable to achieve.

Schapiro has taught two courses — one on the economics of higher education and the other an interdisciplinary humanities class — each year of his NU tenure. He also guest lectures for NU’s schools and at other universities.

Traveling and teaching two quarters of the year, he has to pay attention to both roles. His wife said he has only ever missed two classes: one for the birth of his son and the other while testifying before Congress.

“We’re on the road and running back, trying to catch the last flight back … to make sure he’s back in time to teach his class on Tuesday morning,” said Bob McQuinn, vice president for alumni relations and development.

Schapiro remains a scholar, continuing to research and publish articles regularly. In continuing to teach and write, Schapiro said he does not view himself as unconventional so much as having slightly different priorities. It also helps that his area of expertise directly relates to his “day job,” he said.

“I allocate my time a little differently than a lot of presidents,” Schapiro said.

Schapiro’s unusual approach to his presidency — and his purple-tinged wardrobe — have earned him both strong supporters and harsh critics. (Daily file photo by Ray Whitehouse)

Despite juggling his duties as president, professor and academic, one of his primary responsibilities — fundraising — has not suffered. Schapiro has raised more than $230 million each of the past three years, according to donation surveys. He is currently in the middle of a fundraising campaign to be formally unveiled next year. A similar capital campaign at Williams from 2002 to 2008 resulted in $500,164,885, surpassing the goal by more than $100 million.

Schapiro’s colleagues point to his high energy level and authenticity as attributes that distinguish him from other college presidents. Howard called him an example of “a modern president.”

“He’s a high-motor guy,” Howard said. “He’s everywhere. He can’t help it.”

Marrying undergraduate, graduate priorities

Greater emphasis on student life was one of Schapiro’s priorities from the start.

Instead of hosting a dinner with donors during his inauguration weekend, Schapiro had his administration partner with A&O Productions to bring R&B singer John Legend to campus. A&O Fall Blowout is now an annual concert.

John Legend performs at NU during Schapiro’s inauguration weekend in October 2009. The concert resulted from a partnership between A&O Productions and the administration and grew into the annual A&O Fall Blowout concert. (Daily file photo)

Schapiro has initiated a series of construction projects geared toward student life, including a new lakeside athletic complex, a master housing plan and a new student center, a project he also spearheaded at Williams.

Schapiro’s emphasis on student experience beyond the classroom differs from his predecessor, Henry Bienen, who invested heavily in interdisciplinary graduate and undergraduate research and programming. Bienen established the Roberta Buffett Center, Office of Fellowships and Northwestern University in Qatar while constructing three biomedical buildings and renovating the School of Law.

Schapiro’s predecessor, Henry Bienen, focused heavily on graduate and undergraduate programming during his 14-year tenure. Schapiro has put more emphasis on the undergraduate student experience. (Daily file photo)

Following Bienen’s 14-year tenure, NU was looking for a president who could lead in areas like international citizenship, infrastructure improvement, raising the University’s profile and balancing academic priorities, said Marilyn McCoy, vice president for administration and planning.

Schapiro said his goal is to “marry” high-caliber graduate and undergraduate studies.

“Very few (universities) try to be preeminent in both research and in teaching,” he said. “I was attracted by that challenge. That’s why I took the job.”

Schapiro spends about four days a week in Chicago, monitoring activity at the graduate schools. He has put special emphasis on the Feinberg School of Medicine — NU is moving forward with the installation of a new biomedical research facility at the old site of Prentice Women’s Hospital — and much of Schapiro’s time with politicians is devoted to securing grants for medical research.

After four years, Schapiro has a better grasp on both graduate and undergraduate concerns.

“There are a lot of masters, grad school people and a lot of research that goes on behind the scenes,” said Victor Shao, former Associated Student Government president and a Weinberg senior. “But Morty has done a very good job of accommodating the undergraduate voice.”

A turnaround in town-gown

In 2009, Mayor Elizabeth Tisdahl and her daughters baked cookies and threw a party to welcome the Schapiros to the neighborhood. When Evanston received an $18 million grant in January 2010 for affordable housing, Schapiro sent Tisdahl a congratulatory fruit basket.

Schapiro meets Evanston residents with Mayor Elizabeth Tisdahl. Schapiro has touted his relationship with the mayor as bringing the city and the University closer together. (Daily file photo)

With Schapiro, Tisdahl and several aldermen coming into their positions within months of each other, 2009 was a turning point in town-gown relations. Previous interactions between city and University officials were so poor that in 2009 The Princeton Review ranked the NU-Evanston relationship the 15th “most strained” in the country. Tisdahl refers to the period as the “Hundred Years’ War.”

Disagreement exists over the underlying causes of the tension.

The University would “politely say no” to most of the city’s requests, Tisdahl said.

“Bienen was a great president for Northwestern, but not a great president for the city of Evanston,” Tisdahl said. “President Schapiro is a great president for both.”

However, Bienen pointed to the city backpedaling on zoning agreements and expecting NU to write “blank checks for their budget” as key issues.

Tensions dissolved when Schapiro and Tisdahl took office. The two meet quarterly, and NU and the city now schedule their lobbying days in Springfield together. The city “paints the town purple” during Homecoming, and NU’s Office of STEM Education Partnerships has a physical presence inside Evanston Township High School.

In January, NU and Evanston received a $1 million joint grant to make Evanston an Illinois Gigabit Community, bringing ultra-high speed Internet access to the city and campus.

Although relations between the University and Evanston have considerably improved, Tisdahl admitted they are not perfect. Remnants of “the war” exist among NU’s middle management, she said, and she would like to see Evanston residents employed at NU’s many construction sites.

But the relationship has grown significantly since a decade ago.

“I think the war is officially over,” Tisdahl said.

Making a mark

After four years, Schapiro said it is “too early to tell” what his impact on NU will be.

Controversy and casual mannerisms aside, Schapiro has a comprehensive plan for the University. He typically has with him a worn black planner, its pages filled with scrawled black ink. He also carries an “enormous spreadsheet” detailing the start and completion dates of NU’s numerous construction projects.

With an extension of his contract finalized in October through the 2018-19 academic year, Schapiro, 59, says he has not yet given thought to post-NU plans.

In the meantime, Schapiro said he will continue implementing his 2011 strategic plan, Northwestern Will, and striving to serve the university most effectively.

“I don’t think there’s any area that I do that I think I do as good a job as I should,” Schapiro said. “I should be a better teacher, I should be a better researcher, I should be a better leader, I should engage more successfully with faculty, with staff, with students, with the town. There’s almost everything that I want to be better at.”

Daily file photo