Even before she came to campus for an admitted student day last April, Weinberg freshman Karley Woods heard about the tense state of race relations at Northwestern, an issue that made her hesitant to enroll.

“It was just around that time when all the bias incidents were occurring,” she said. “Obviously, it’s not the most positive thing to read about a school that you are looking into.”

Woods’ visit was organized by Ambassadors, a program that recruits prospective black students. After visiting the multicultural community, she decided she wanted to help make campus more inclusive.

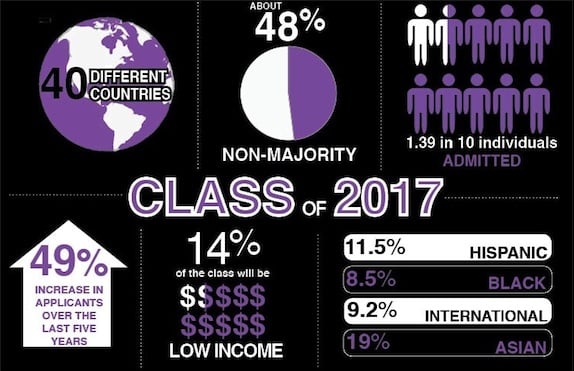

Last fall, Woods joined NU’s increasingly diverse student body, the result of concerted efforts by the Office of Undergraduate Admission to draw greater numbers of black, Hispanic, international and low-income students. Nearly 50 percent of the class of 2017 will be “non-majority students,” as described by University officials.

With a more than 10,000-application increase and an acceptance rate that has been cut almost in half since 2007, NU is reaping the benefits of a five-year recruitment strategy that has seen unprecedented success. Part of that plan involved sending admissions officers to more high schools across the nation and the world, with the goals of increasing the applicant pool and attracting top students from a range of backgrounds.

Increased diversity aside, numeric gains have not necessarily translated into a more inclusive campus. Some students and faculty members say a heavy focus on numbers is not enough, given recent incidents and discussion surrounding diversity over the last year.

“It doesn’t matter if you bring — instead of 200 Latinos — 300 Latinos, if they are not going to feel safe,” said Sobeida Peralta, co-president of Latino student group Alianza.

A recruiting revamp

When Christopher Watson, dean of undergraduate admissions, came to NU in 2007, he was ready to improve the recruiting process.

He helped divide the admissions office into nine recruitment regions — eight for the United States and one for other countries. NU admissions officers also doubled their on-the-road travel time to five weeks. The University increased its recruiting efforts from about 300 high schools in 2007 to about 1,300 this year.

“We didn’t want to make the assumption that everyone was going to come to us or that they could come to us, so we needed to go to them,” Watson said.

The new strategy’s success has been reflected in the numbers.

In the last five years, applications have risen more than 49 percent to about 33,000. The admit rate dropped from 26.8 percent to 13.9 percent. And the percentage of admitted students committing to NU in the spring grew from 33.7 percent to an estimated 44.5 percent.

Early Decision applications reached an all-time high for the class of 2017, with 2,651 applicants, said Michael Mills, associate provost for university enrollment. A record 43 percent of the class of 2017 was admitted early decision because more applicants were qualified, Watson said.

Although NU has worked to send recruiters to potential students, more students than ever are coming to Evanston. Visits to campus have doubled since 2007 to 50,000 visitors a year. The current admissions office at 1801 Hinman Ave. is getting crowded, increasing the need for the new lakeside visitor center that is slated to open in 2014, Watson said.

A more diverse NU

Hispanic, black, Asian-American and international students will make up almost 50 percent of the class of 2017, an unprecedented proportion.

“Twenty percent of freshmen who have deposited for next fall are African-American or Hispanic,” Mills said. “It just shatters the all-time record, which was set last year at 16.7 percent.”

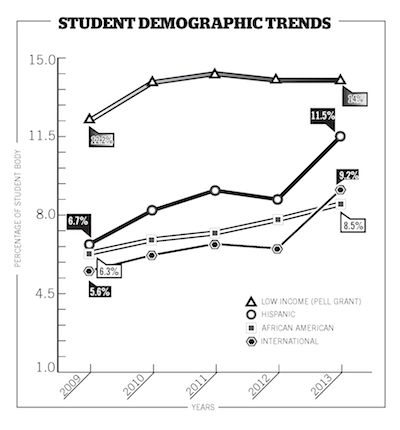

The percentages have been slowly rising since 2007. Next year 8.5 percent of the incoming class will be black, an increase from 5.6 percent five years earlier. Hispanics will represent 11.5 percent, compared with 7.4 percent in 2007.

Onis Cheathams, director of multicultural recruitment for almost a decade, said NU’s heightened outreach efforts and exposure have made the difference when it comes to diversity.

“We put in a lot of hours, a lot of time recruiting students,” Cheathams said.

The new regional recruitment strategy made admissions officers responsible for increasing underrepresented students in their areas. As NU representatives forge stable connections with individual high schools, they are better able to recruit students.

The office is working to specifically target high schools with diverse populations. The University subscribes to databases that provide details on individual high schools, including the racial and ethnic breakdown of the student bodies, Watson said.

“Five or six years ago is when we started to focus on this really intently,” Mills said. “Things have just snowballed in a positive way since then.”

NU also draws from a database of more than 300 national and community-based organizations that work with universities to reach underrepresented students.

To put the gains in context, Mills noted only six of the 30 other elite member colleges in the Consortium on Financing Higher Education had combined Hispanic and black populations that were 20 percent or more of their student body last year.

“We would be more diverse than Harvard, Princeton, Yale,” Mills said. “That’s quite an accomplishment.”

The University hosts special programming for underrepresented students during Wildcat Days to persuade them to enroll at NU once they are admitted. Students stay with members of the multicultural community on campus.

“During my time here, they really exposed us to what you can call the minority community here,” Woods said. “Some of my best friends today I met at Wildcat Days.”

NU also increased its low-income population. Fourteen percent of the class of 2017 will be students with a federal Pell Grant, compared with 9.1 percent in 2007.

The incoming freshman class will include the first 10 students from NU’s partnership with the Los Angeles site of the Posse Foundation, which pairs students from diverse backgrounds with elite schools. It will also boast the highest number of students from QuestBridge, a nonprofit that matches low-income students with scholarships at top-tier colleges and universities.

‘What happens inside of Northwestern?’

During the second of two annual forums with University President Morton Schapiro last month, Medill Prof. Doug Foster asked about NU’s plans for fostering a more diverse campus “after students get here.”

In his response, Schapiro acknowledged numerical gains are not enough.

“We haven’t created yet the inclusive community that our faculty, staff and students deserve, and frankly the one that we advertise,” he said.

Some students agreed making the NU community more diverse does not necessarily make it more welcoming.

“It’s good for the University’s image to say, ‘Well, now instead of 9 percent, we have 11 percent that are Latino,’” said Peralta, a Weinberg sophomore. “But then what happens inside of Northwestern? Because the 11 percent don’t feel they are a part of Northwestern.”

Racially charged incidents, such as the alleged hanging of a black stuffed bear from NU maintenance worker Michael Collins’ desk, perpetuate the idea students of color are not wanted, Peralta said.

SESP freshman Qiddist Hammerly visited NU during Wildcat Days last spring to meet with the multicultural community. Hammerly said at first she was nervous about coming to NU because she had heard stories about a tense racial climate.

“I was coming from a high school that was fairly similar to Northwestern,” she said. “I was just kind of tired of that and was not looking to repeat that in my college experience.”

Mills said he attends as many protests and student gatherings on diversity as he can. Aware that some students do not feel NU is a welcoming place, he said his job is to produce a “critical mass” of every kind of student.

Like Schapiro, Mills noted NU’s increasingly diverse classes are the best way to measure the University’s progress, at least from an admissions-based standpoint.

“I do not think that when we talk about numbers it’s meant to veer attention away from the problem that exists on campus,” Mills said. “We’re just excited that there are more diverse students coming to Northwestern.”

Hayley Stevens, outgoing associate vice president for diversity and inclusion of Associated Student Government, said the University is doing its best to build “a truly diverse class.”

Although NU has hired diversity-related administrators, recent incidents of racial bias have not been handled well, Stevens said.

“These things are happening here and, sure, they might be a PR nightmare, but they happened here on your university and you need to be accountable for it,” Stevens said.

Going global, local

NU has stepped up recruiting in the Chicago area, with admitted students from Chicago Public Schools increasing about 31 percent since 2009. Eleven students from Evanston Township High School have committed to come to NU this fall, the highest number since 2007.

Because CPS has many students from underrepresented groups and potentially first-generation college students, they add more diversity to the freshman class, Watson said.

In addition to recruiting in its backyard, NU has greatly increased the number of trips overseas over the last five years, recruiting in 25 countries during each of the past two years.

The global emphasis has led to an uptick in international applications, which increased 4 percent for the class of 2017. This fall, 9.2 percent of the freshman class will be international students, up from 4.7 percent in the 2007-08 academic year.

This academic year was the first the admissions office traveled to Africa, visiting Kenya, Ghana, Swaziland and South Africa.

The greatest number of international applicants comes from Asia, as is the case in most American universities, Watson said.

International students represent 40 countries in the class of 2017.

Watson and Mills credit Schapiro’s exhaustive travel schedule with promoting NU overseas. Schapiro appears on television and does interviews with newspapers when he travels to Singapore and China.

“He devotes most of the summer to travel everywhere to meet with Northwestern alums and incoming freshmen,” Mills said. “That has to be playing some role.”

Choosing NU

The University relies on teams of students to persuade underrepresented groups to enroll once they are accepted. In addition to the efforts of Ambassadors, the Council of Latino Admission Volunteers for Education helps recruit and enroll prospective Hispanic students.

Alexandria Bobbitt, a student coordinator for Ambassadors, said she has encountered students who worry about NU being a predominantly white institution and want to know if there are other minority students on campus.

“It’s important to know that you are represented here in some way before you come,” said Bobbitt, a SESP freshman.

Both CLAVE and Ambassadors host visiting students, send letters and make phone calls. Students from the multicultural community volunteer with these organizations and meet with students when they come to NU.

Weinberg freshman Joel Guajardo said NU paid for his visit for Wildcat Days last April after he was admitted Regular Decision. He stayed with Latino students while on campus.

Guajardo is from Brownsville, Texas, an overwhelmingly Latino city near the U.S.-Mexico border. He said the size of NU’s Latino population was not a deciding factor in his enrollment decision, but his visit reassured him it was “not nonexistent.”

“It showed me there is a Latino community here on campus,” he said.

Woods and Hammerly said upon getting to campus and seeing students’ commitment to improve inclusion, they were inspired to join the efforts. Hammerly is on the executive board of For Members Only. Woods is also a member of FMO and on the ASG diversity and inclusion committee.

“Seeing that all those incidents were happening,” Woods said, “I just realized that I don’t want other prospective students to have to go through that same prospective experience, with that negative light shed on Northwestern from day one.”