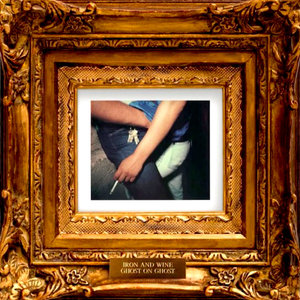

The charming, disarming melody of “Winter Prayers,” on Iron and Wine’s “Ghost on Ghost,” released April 16, reminds listeners of an earlier age. Gentle guitar strumming and delicate piano notes resemble the music of a younger Sam Beam, an artist who could not have accomplished “Ghost on Ghost” five albums ago. But the progress from folk minimalism comes at a price: The album at times feels disjointed and inconsistent.

“Ghost on Ghost” opens with an erratic pulsing of clacking sounds and a whining guitar on “Caught in the Briars.” Then, as if the previous 25 seconds didn’t exist, a striking guitar lick introduces a section of chanting horns and auxiliary piano. Beam’s singing transforms into a vigorous, sparkling piano solo, which in turn fades into the next song.

“The Desert Babbler” brings a falsetto of choir boy humming and minimalist snare drums. It sneaks a calm breeze of harmony into the combination of instruments and vocals. For its part, “The Desert Babbler” functions well and gives the album a hint of definition.

But the next track, “Joy,” is anemic, sickly and bitter to the ears. The nostalgic, uplifting message heard in the previous two songs disappears just as quickly as it appeared. Beam sings over the cadence of a gentle piano, but his lyrics are lost to the melancholy instrument. His lugubrious tone is, for the most part, offsetting.

Beam himself said he wanted to move away from the “anxious tension” found in his previous two albums. “Ghost on Ghost” was a “reward” in comparison to the production of his other compilations.

Yet tension arises in this album as well, even if Beam creates it accidentally. Perhaps musically “Ghost on Ghost” contains none of the angst to which Beam refers, but the arrangement itself lacks a progression. Instead it regresses into a roller coaster of musical experimentation, without a semblance of intent. Beam synthesizes new tunes merely for the purpose of moving in a variant direction.

This frustrating truth is inescapable. Beam crowds certain songs with sonic decoration; the next perfects a simple tune with soft euphony; then he settles into imagination, wistfully injecting lyricism. The album’s distinction from Beam’s prior work emerges when innovation is bold but not forced.

“Lovers’ Revolution,” the penultimate track of “Ghost on Ghost,” is a simmering jazz ballad, full of stair-stepping melody and finger-snapping rhythm. But the folk-turned-jazz ensemble harms Beam more than it helps him. The awkward, six-minute song protrudes from “Ghost on Ghost” like a disgusting scar. It resembles none of the preceding tracks. Instead, it extends in the opposite direction.

“Ghost on Ghost” is a valiant effort, a charismatic enchantment of indie folk rock. Energy abounds. Beam merely needs to consider execution and arrangement before his next attempt at musical self-characterization.