Last month, hundreds of thousands of visitors to the gossip website Gawker.com came to know Northwestern students as the epic ragers whose drunken antics had made Dean of Students Burgwell Howard “apoplectic.”

The irony was not lost on some – or perhaps anybody. NU’s notoriously not-so-Big Ten party scene was suddenly elevated to “epic rager” status, achieved via public urination and vomiting, profane sexual references, and general raging. The behavior spawned a slew of angry e-mails and phone calls to NU administrators and city officials, prompting Howard to send an angry e-mail of his own to the off-campus listserv, the text of which was later posted on Gawker.com.

It was a new low – at least in terms of blogosphere notoriety – for town-gown relations; that broad nexus of students, the University, nonstudent residents, local businesses and the city officials charged with representing them all.

As a 33-year Evanston resident who has spent the last 11 working as NU’s special assistant for community relations, Lucile Krasnow described the goodwill and enmity on both sides as “an ebb and flow.”

While that exchange is difficult to quantify, a 2006 economic impact study put the flow of University-related cash to the city at $160 million annually.

“Go ask a local printer,” Krasnow said. “They’ll laugh. They kind of go, ‘We couldn’t exist without Northwestern.’ Start with Taco Bell and move from there. It is unbelievable the influence that students have on the economic well-being of our fine city.”

But where the Chamber of Commerce sees in NU students an economic asset, some neighbors just see inconsiderate asses. One source of tension has been the student population’s inexorable westward migration.

Go west, young Wildcats

NU students’ western frontier has expanded over the last decade. Taking advantage of the real estate boom, single-family homes in neighborhoods west of campus – often empty nesters or families looking to downsize – have been sold to developers or real estate companies.

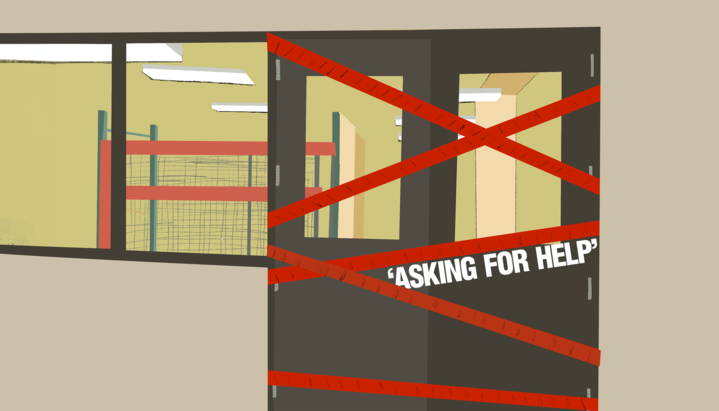

It’s a transition that has included increased population density, as many developers split these single-family homes into multiple-flat rentals that cash-strapped students typically snatch up. Often these houses are in violation of a city ordinance that prohibits more than three unrelated people from cohabiting. For NU students, off-campus living can be fraught with difficulties, from exploitative landlords to neighbors less than thrilled by students’ manifest destiny and the associated impact on the neighborhood.

“For many of the permanent neighbors, the neighborhood has changed out from under them.”

-Dean of Students Burgwell Howard

“There are more cars parked in the street, there’s more trash being generated, there’s more noise and there’s much more activity in the neighborhood than there was 10 years ago,” Howard said. “For many of the permanent neighbors, the neighborhood has changed out from under them.”

Among other issues working against students, a house’s reputation may bring unwarranted preconceptions to the unknowing new student neighbor.

SESP junior Eli Cadoff – whose house had a “fairly notorious” reputation – said he and his housemates made a point to introduce themselves to neighbors as the house’s new, less rowdy occupants. But a Wildcat Welcome Week party was apparently still too boisterous. When a police officer knocked on their door to inform them he could “hear voices,” Cadoff’s housemate asked the officer if that was a problem.

“They were kind of like, ‘Well, no,'” Cadoff said. “So we didn’t get a formal noise complaint or anything like that.”

Two weeks later, Jim Neumeister, NU’s director of student conduct, summoned the Gaffield Place residents to his office, requiring them to submit a “plan of resolution” detailing how they would avoid similar “non-incidents,” as Cadoff refers to that night.

“We don’t have issues with ‘the town,’ we have issues with the University,” he said.

Every administrator and many students and non-student residents interviewed for this article emphasized the importance of dialogue between students and their nonstudent neighbors.

“Hopefully the neighbors will be generous in spirit enough to consider it a fresh slate and a new year and let these particular student residents speak for themselves in terms of their behavior,” Krasnow said.

Tonight, Howard will host “Community Conversations,” a forum for student and nonstudent neighbors to do just that.

Beautiful Days in the Neighborhood

Gorgeous fall weather the day of the Purdue game undoubtedly contributed to the size and intensity of tailgate festivities. In response to that Saturday’s events, City Manager Wally Bobkiewicz said a new ordinance placing limits on backyard gatherings might be considered by the City Council early next year.

“There is definitely concern in the community about what we can do to manage these activities a little bit better than they have been,” Bobkiewicz said.

The days of 200-person epic ragers may soon come to an end, but as Ald. Delores Holmes (5th) points out, any ordinance would affect all Evanston residents.

“We would never have an ordinance that would just be earmarked for students,” she said. “So you have to consider that in terms of people having barbecues or wedding receptions or anything else in their backyard. I’m sure there will be lively discussion when it comes up.”

With football season winding down and cold weather settling in, some of the rowdy behavior will likely tail off – for a few months, anyway.

In early May 2010, students emerged from the doldrums of Winter Quarter in a way that was too rowdy for Howard, who sent a similarly stern e-mail blast via the off-campus listserv.

“And while the University does want students to enjoy the weather, and each other, it is a VERY real concern that the actions of a few … can have a very real and serious impact on events and activities later this quarter, and with future relations with the City,” he wrote on May 1.

In an interview with The Daily a few days later, Howard made an almost inconceivable threat: the potential cancellation of Dillo Day, if students’ conduct did not improve.

Teach Us How to Dillo

Dillo Day was not canceled, but did see a record number of citations issued. Howard insists the 43 citations to NU students were the result of increased law enforcement personnel devoted to the neighborhoods west of campus. The previous two Dillo Days each saw just 11 citations issued to NU students.

“I think last year we caught more fish in the net because we had a tighter net,” Howard said.

Dillo Day presents the perennial test of the town-gown bond. In the ups and downs of town-gown relations, there’s no denying that one Saturday’s destructive potential.

“It’s never linear,” said University President Morton Schapiro in a recent interview with The Daily. “So things get a little better, then you have a bad weekend and you have Dillo Day, which sets you back.”

Following a particularly unruly Dillo Day 2003, then-Dean of Students Mary Desler formed a task force of students, administrators and community members to work on improving students’ safety and ensuring the day brought as little strain as possible. Some of the work is about ratios and sociological equations.

“If you put four kegs in that backyard and 200 people show up and you’re at it all day, there are going to be problems,” said Matt Doherty, an Evanston resident on the task force.

Whatever Dillo Day does to the atmosphere and aesthetics of the neighborhoods west of campus, it is nothing compared to the scene 110 miles northwest in Madison, Wisc. The annual Mifflin Street Block Party takes place in early May, bringing tens of thousands together on one student-saturated block. I

n a state known for its drinking culture, at a university known for its partying, Mifflin is University of Wisconsin-Madison students’ collective ode to alcohol. Madison police issued 316 citations during Mifflin 2010, but notably, just 46 were given to UW-Madison students.

Mark Gallo, a UW-Madison junior, has been to both Dillo Day and Mifflin the last two years.

“The first time I came to Madison, I was a freshman in high school,” he said. “We were just walking around – it was a game day - and I remember we went to my cousin’s place and the apartment next door had a three-story beer bong.”

As a sophomore at UW-Madison, two noise complaints were the extent of his house’s interaction with law enforcement on a block inhabited by almost all students.

“We drank a lot,” he said. “We wrecked just about everything in that house.”

Head south to the University of Chicago, and in a relative way, NU students begin to look like the party animals they were portrayed as on Gawker.com. At the school’s 2010 Summer Breeze concert and carnival, university police logged no citations or arrests related to the festivities.

“We had a pulled fire alarm, a missing vehicle and a shoplifting incident. That was all,” said Robert Mason, the university police’s public information officer.

So where does NU ultimately lie on the debauchery-space-time continuum? Somewhere between the Badgers’ three-story beer bongs and the Wildcats’ peers to the south, “Where fun goes to die.”

“The thing I think about when I go to Northwestern is, it’s like getting drunk for the first time with the top 5 percent of your high school class,” Gallo said.

The Princeton Review rolls out annual rankings on a number of aspects of college life, and this year, NU slipped out of the top 20 in the category “Town Life: Town-Gown Relations are Strained.” The rankings are based on an 80-question survey administered at 373 colleges.

But NU’s departure from the list may not mean a whole lot. James Hughes, director of the office of Institutional Research and Planning at Trinity College in Hartford, Conn., takes exception to the Review’s methodology and the legitimacy of their rankings. Trinity ranked No. 1 in the category this year.

“They don’t release figures on how many students have answered the survey from each school or the specific questions that they use to create their lists,” he wrote in an e-mail.

‘A different school experience’

About a month ago, the Office of Student Affairs appointed Betsi Burns assistant dean of students. Burns will devote up to half of her time to off-campus concerns.

She “hit the ground running” in her new role: Her first day on the job was Oct. 11, two days after Howard’s post-tailgate e-mail. One of Burns’s first projects will be putting together a student advisory board to bring students’ perspectives to off-campus issues. Howard’s office will collaborate with the Associated Student Government to develop a website to serve as a resource for off-campus students.

“Are we going to keep everyone happy all the time and have folks out in the streets singing Kumbaya all the time? Probably not,” Burns said. “But can we do things to encourage a dialogue and make things better? Absolutely.”

NU administrators are also looking to other schools for ideas. Howard describes Colorado State University’s off-campus office in Fort Collins, Colo., as a model NU is examining. CSU students can register their off-campus parties with the university, reducing the consequences of noise violations and neighbor complaints. The office goes so far as to distribute free “party packs” with practical items like trash bags, “neighbor notice sheets,” and information on relevant city ordinances and law enforcement practices.

Almost 80 percent of CSU’s 26,500 students live off campus, significantly more than the 3,000 to 4,000 NU undergraduates who live off campus in a given year.

“I think it’s a matter of having a lot of tools in your tool belt - to try to address problems from different angles for different people,” said Jeannie Ortega, CSU’s director of off-campus life.

Doherty, from his vantage point on Maple Avenue, remains optimistic about the future of neighborhood relations. He recalled a story that may just go to show that the more things change, the more they stay the same: Invited to a student party in the late 1980s, Doherty watched a cadre of NU students struggling to tap a keg.

“It was a lot of engineering students, really smart people. I said, ‘I can’t believe I’m at a college party, and you guys can’t get the tapper into the keg.’ And without missing a beat, a female student turned to me and said, ‘No, but I can tell you where all the fatigue points are.’ I thought, ‘This is a different school experience.'”

andrewkaspar2011@u.northwestern.edu