As Sabrina Siddiqui headed to class last Wednesday morning, she walked carefully on a Sheridan Road sidewalk that had turned into a makeshift ice skating rink.

Her winter boots did not act as ice skates.

The Medill senior slipped, falling on her lower back, which she said is still sore almost a week after the incident.

“I always remember there being a lot of snow, but I never remember the sidewalks being so icy that you couldn’t even walk properly,” Siddiqui said. “It is putting people at danger and at risk.”

The icy sidewalks and streets are as a result of Evanston suffering from a salt shortage that is hindering snow and ice removal from streets and sidewalks and that will last through the winter, city officials said.

The shortage, which has affected cities across the Midwest, comes from an especially snowy and icy winter, which has caused demand for road salt to spike. But suppliers have not been able to meet the increased demands.

Evanston usually uses 5,500 tons of road salt, but this year the city has already used more than 8,000 tons due to the extreme conditions. A ton of salt costs about $30, according to the National Research Council.

The extra 2,500 tons, which was delivered to the city after an emergency request, was both a blessing and a curse, said Suzette Eggleston, superintendent of Evanston’s Streets and Sanitation Department. The extra salt has helped to keep the roads salted in the wake of recent snowstorms, but it decreases the likelihood that Evanston will receive more shipments the rest of the winter. Other cities haven’t even received the amount they originally asked for, and their contracts must be honored by suppliers.

“Our supplier has indicated that they owe us about 1,200 tons of salt,” Eggleston said. “Basically they cut us off in the middle and don’t anticipate being able to deliver that to us until the end of the season.”

In response, the Streets and Sanitation Department is using salt on major roads only – such as Dodge Avenue, Sheridan Road and Chicago Avenue – while using a mix of sand and a liquid de-icer on some residential streets and intersections, said Evanston Public Works Director David Jennings in a Feb. 7 newsletter to citizens. The de-icer, called Geomelt, and the sand give the roads traction but don’t have effective melting capabilities.

The effort is an attempt to conserve the 1,000 tons of salt the department has on hand, officials said. The city also switched to using the more expensive bag salt on sidewalks and parking lots, and stopped selling salt to Northwestern and other school districts.

The city is supplementing these actions with regular snow plowing, which has helped to clear many streets. Still, the policy has changed how some Evanston streets look, especially after the storm last week.

“We have stopped salting residential streets, but are continuing to plow,” Jennings said in the letter. “This means that most of these streets will develop ‘snowpack’ which is smooth in some areas, but tends to rut and develop a washboard surface as traffic packs it down.”

The “snowpack” has not caused the roads in Evanston to be less safe than usual, Eggleston said.

“Streets are dangerous every day; accidents happen every day, ” she said. “Did we leave the roads in a hazardous situation? No, not to our mind.”

Statistics tell a different story.

Inadequate salting of the roads can be very dangerous, said Richard Hanneman, president of the Salt Institute, a nonprofit trade association.

“If you apply salt to roads within the first hours after storm, you reduce injuries and accidents by 88 percent,” Hanneman said, citing a study from Marquette University’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

The main danger of not using salt on the roads is that it can lead to slicker roads.

One Evanston resident said she had heard about the salt shortage, but that she didn’t feel she was at a much higher risk of getting into an accident.

“I just drive slowly,” said Marybeth Shroeder, a 17-year resident. “It’s just a little bit annoying, but it’s just a convergence of lots of forces – the snow and ice and everybody’s out of salt.”

Shroeder added that this winter has been significantly snowier and colder, a trend that’s been seen across the country.

“Maybe Al Gore was wrong; global warming won’t take care of winter,” Hanneman said.

City officials also take the situation with a little bit of humor in addition to their concern.

“The award for the most innovative suggestion on how to resolve the current salt shortage comes from the citizen who wonders out loud, ‘If we all filled up our pockets with the salt packets from fast-food restaurants, could we pool those resources and make a difference?’ ” wrote Jennings in a separate Feb. 7 letter. “Unfortunately, no. Creative, but not too practical.”

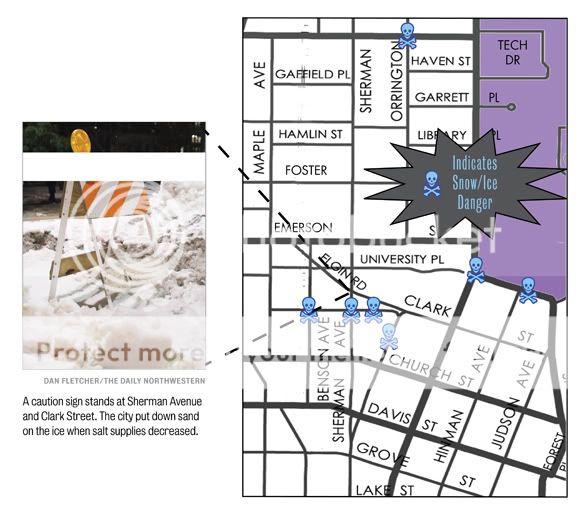

dan fletcher/the dailyA caution sign stands at Sherman Avenue and Clark Street. The city put down sand on the ice when salt supplies decreased.