Community Data Walk shows health and quality of life inequalities in Evanston

Shannon Tyler/Daily Senior Staffer

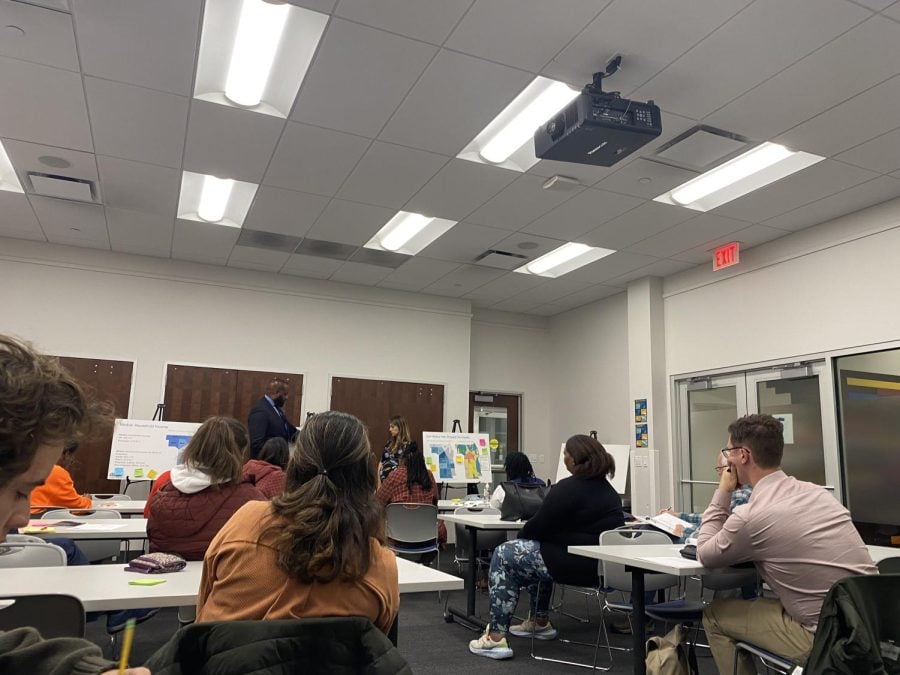

Community members gathered in the Youth & Opportunity United building Thursday night to learn about the results of the city’s study.

October 13, 2022

More than nine decades after Evanston’s first redlining policies went into effect, Black neighborhoods in Evanston still have fewer resources than white ones, according to a data set presented by Evanston Cradle to Career and the city in a joint presentation Thursday.

About 12 community members gathered at the Youth & Opportunity United building to discuss findings on the inequalities in health and quality of life for Black residents.

Walking participants through six posters depicting graphs of their data, Evanston pastor Monte’ L. G. Dillard Sr. and community health specialist Kristin Meyer showed participants how Evanston’s redlining map from 1935 to 1940 looks similar to today’s segregation in resource investment.

“A lot of (these) places remain very much the same,” Meyer said. “As we walk through … where health and wealth is concentrated, that’s also where we see that concentration of white residents.”

Meyer said the data shows that concentrated assets and harms around Evanston contribute to the disparities in health levels and quality of life seen in the different wards. Evanston’s Health and Human Services Department recently found that residents of the historically Black 5th Ward have a life expectancy five to 13 years shorter than residents in neighborhoods with more predominantly white populations.

Residents in the 5th Ward have a life expectancy of 75.5 years, while residents in the majority-white 7th Ward, have a life expectancy of 88.8 years, according to data presented at the walk.

Cradle to Career advocate Ndona Muboyayi said the issue goes deeper than disinvestment.

“We tend to talk about wealth, meaning that the concentration of wealth was only in the white community,” Muboyayi said. “There was at one time wealth within the Black community, and we’re not talking about how there was a lot of wealth stolen from the Black community.”

Muboyayi distributed a pamphlet outlining the history of Evanston’s 5th Ward.

The brochure included illustrations of the first hospital in Evanston for Black residents, which opened in 1914.

Dillard said the data should put to rest a common misconception that the health disparity in low-income communities comes from individual choices.

“A person can have as much will as they want,” Dillard said. “But they will always be limited by the options that are available in their community.”

The city broke down census data into 18 neighborhoods. Data included the makeup of race in each ward, premature deaths by race, median household income and life expectancy by ward among other topics.

Evanston ranks well above the national average in median household income. But the data map shows that average is heavily skewed by wealthy districts along the lakefront and northern and eastern corners of the city, Dillard said.

Evanston’s Participatory Budgeting Committee sought input for how to spend $3.5 million of federal money from the American Rescue Plan Act in ways that will benefit the community through a participatory budgeting program.

Community members discussed ideas for possible ARPA funding including investing in reparations, guaranteed healthcare and zoning equity.

“When we talk about stealing assets away from community members, what more precious asset is there than life itself?” Meyers said.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @shannonmtyler

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @albergasimon

Related Stories:

— The lasting impacts of Evanston redlining

— A history of initiatives and attempts to increase affordable housing in Evanston