Native Americans in Chicago chart a 15 percent COVID-19 mortality rate — but the city hasn’t released that information

The new American Indian Health Service of Chicago clinic. “Our new clinic … took years to advance due to limited funds from the Indian Health Service,” Unabia said in an email. “Sadly, with two full time providers on staff, we have already outgrown this clinic.”

June 22, 2020

COVID-19 is killing the American Indian residents of Chicago at disproportionately high rates, but the city has chosen to keep those statistics under wraps.

RoxAnne Unabia, interim executive director for the American Indian Health Service of Chicago, said as of June 16, 23 percent of her clinic’s COVID-19 tests have returned positive since AIHS started testing at the end of April. That’s 7.5 percent higher than the overall positivity rate in Chicago during the same time frame, according to city data.

However, while Illinois includes the American Indian and Alaska Native population as a separate category in the state’s demographic breakdowns for COVID-19 data, Chicago categorizes the population as “other.”

“It’s really hard for us to track how many American Indians have gone to other facilities to be tested,” Unabia said. “(We can’t tell) what numbers they’re reporting when we’re just categorized as ‘other.’”

A Freedom of Information Act request revealed 261 COVID-19 tests were administered to American Indian and Alaska Native individuals living in Chicago from March 1 through June 11. Of those tests, 46 returned positive — an 18 percent positivity rate falling slightly below Chicago’s 20 percent positivity rate for the same interval.

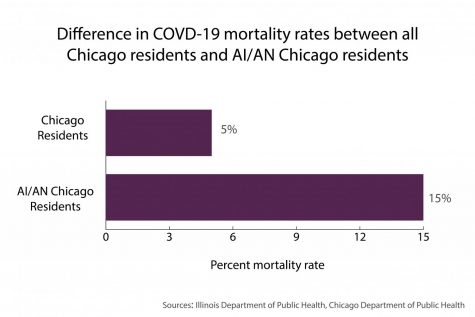

However, seven of those who tested positive have now died as a result of COVID-19, charting a 15 percent mortality rate — triple Chicago’s overall 5 percent mortality rate during the same period.

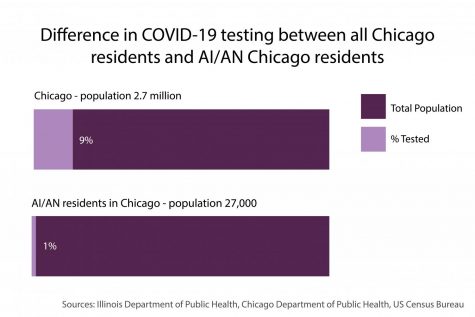

Testing per capita rates are also vastly lower for the Indigenous population than for the city as a whole.

About 27,000 American Indian and Alaska Native people live in Chicago, which has a population of 2.7 million people overall, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Less than one percent of the city’s Indigenous population received a COVID-19 test during the March through mid-June interval, while nearly 9 percent of Chicago’s overall population was tested for COVID-19 during the same period.

Juliet Larkin-Gilmore, a postdoctoral fellow studying 20th century Native health at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, said the city’s choice to exclude Indigenous people from data disaggregation follows a long history of “statistical erasure” for the American Indian community.

Chicago holds the largest American Indian population in the Midwest. However, because their numbers are relatively small compared with other demographic groups, Larkin-Gilmore said institutions frequently overlook Indigenous people in statistical breakdowns. As a result, they’re wiped out of the conversation.

“It makes it impossible to address any Native-specific health concerns,” Larkin-Gilmore said. “If you can’t see it, you can’t fix it. You can’t think about tribally specific healing practices, healing systems. You can’t integrate that with biomedicine, if you’re not paying attention to it. That has a lot of really deadly consequences.”

Settler violence has historically unleashed epidemics upon American Indians. When European colonists arrived in the Americas, they brought a smallpox epidemic that wiped out more than 70 percent of the Indigenous population. Centuries later, the 1918 flu pandemic killed American Indians living on reservations at four times the rate of the general population.

Today, coronavirus is taking a similarly vast toll on American Indians across the country, with the Navajo Nation and White Mountain Apache Tribe charting the highest per capita COVID-19 infection rates in the United States.

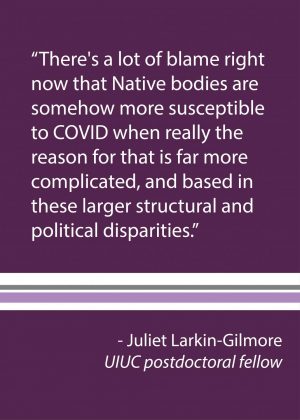

“There’s a lot of blame right now that Native bodies are somehow more susceptible to COVID(-19),” Larkin-Gilmore said. “When really the reason for that is far more complicated, and based in these larger structural and political disparities.”

In 2018, the unemployment rate for American Indians and Alaska Natives was almost 7 percent — nearly double the rate for white Americans at the time. Native Americans also chart the highest poverty rates in the country.

“For people to remain healthy, they have to have housing, employment,” said Dorene Wiese, CEO of the American Indian Association of Illinois. “They have to have access to good, healthy foods. They have to have access to family planning… and our community does not have many of those services.”

Wiese said there is a dearth of Indigenous licensed social workers in Illinois, meaning it’s difficult to connect American Indian people with social services. Additionally, she said the population’s rates of access to the internet — and consequently, to critical information about COVID-19 — are staggeringly low.

As a result of this cocktail of structural inequities, American Indians are at high risk for complications from COVID-19.

They’re twice as likely to have diabetes compared with the white population, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They’re also significantly more likely to deal with asthma, heart conditions and the other underlying factors that worsen the effects of COVID-19.

Due to comorbidities like uncontrolled diabetes and autoimmune disorders, AIHS of Chicago Director of Diabetes Melissa McGee said four individuals at her clinic have tested positive for a month or more after their initial diagnoses. One individual had COVID-19 for more than six weeks.

Amid centuries of violence and expulsion, the U.S. government signed hundreds of treaties with American Indian tribal nations that promised funding for basic provisions: health care, education, housing and economic development, among other services.

“There is a legal and historical obligation for the United States to provide health care to (American Indians),” Larkin-Gilmore said. “And that is not happening.”

Although over 78 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives live outside reservations, Urban Indian health programs receive less than one percent of Indian Health Service funding — which is already sparse.

Providing medical care for 2.2 million of the country’s 3.7 million American Indian and Alaska Native people, the IHS has suffered underfunding since its 1955 inception. The IHS spent just over $3,000 per patient in 2017, while that same year Medicare and Medicaid spent nearly $13,000 and $8,000 per patient respectively, according to a National Congress of American Indians report.

With funds stretched thin, Unabia said the IHS is only able to provide basic care for the conditions that exacerbate COVID-19.

Urban Indian health programs, Unabia added, are smaller. They lack emergency rooms. They run with minimal capacity to provide long-term care for those with chronic health conditions.

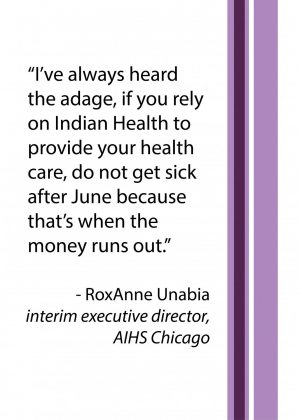

“I’ve always heard the adage, if you rely on Indian Health to provide your health care, do not get sick after June,” Unabia said. “Because that’s when the money runs out.”

As COVID-19 set in, the Chicago American Indian Community Collaborative stepped up to supplement deficient city resources. CAICC is providing medical supplies, food and shelter among other resources to those in need.

Heather Miller, executive director of the American Indian Center of Chicago, collaborates with the organization’s food bank, organizing the distribution of weekly food baskets to members of the Indigenous community.

“(COVID-19 is) a crisis, but we’re in a crisis every single day, so this is normal for us,” Miller said. “I see it like nothing is different … we have things to change. We have situations to improve upon, and we’ve got tons of work to do. So at this point, my job is to take care of my community and to get the work done.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @maia_spoto

Related Stories:

— With limited resources, Chicagoland Native American groups step up to help their own