As overall violent crime goes down, gun violence still vexes city

April 28, 2016

Emeric Mazibuko is already worried about the next victim of gun violence in Evanston.

Mazibuko, the street outreach case manager for Youth & Opportunity United, has worked with the city’s at-risk youth through Y.O.U.’s street outreach program for six years. He said he sees firsthand the impact of violence on children who live near areas in the city that have a high rate of crime — or who know the victims of crime personally.

“It’s been tough. It’s been very difficult,” Mazibuko said. “This is supposed to be a suburb where people say, ‘Wow, I want to raise my kids there,’ and yet the things that are happening to the young men of color around the country are happening here too.”

Through his work, Mazibuko says he has been touched by the deaths of young men killed in recent years, such as 20-year-old Benjamin “Bo” Bradford-Mandujano, who was killed in January.

Bradford-Mandujano was one of two young men killed in Evanston this year. The other, 19-year-old Star Paramore, was found dead in a south Evanston basement in March. A third Evanston resident, Antonio Johnson, 18, was also killed in March, just south of Howard Street in Chicago.

Susan Trieschmann, who runs Curt’s Cafe — a non-profit focused on training at-risk youth in food-service careers — said Bradford-Mandujano’s death was a shock. He had been a student at the cafe since November, and his death has led Trieschmann to understand the devastating effects of losing someone to violence.

“When you go through something like that, you just look at things through a different lens,” Trieschmann said. “We’re all still experiencing some PTSD.”

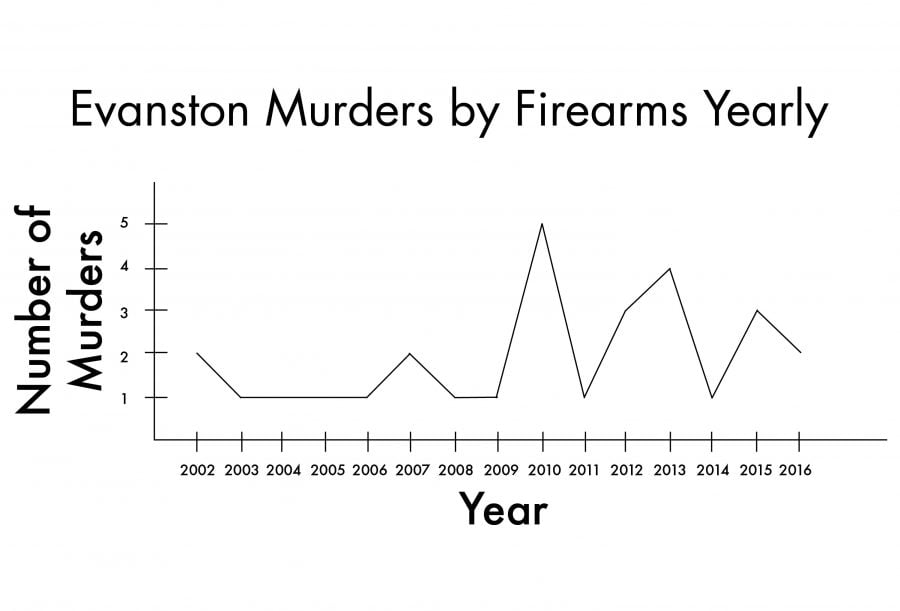

The two murders in Evanston this year have also been alarming for some city officials and community members. Although the city’s homicide rate involving firearms has stayed fairly steady — at most five per year since 2002 — the overall violent crime rate has been decreasing.

According to Evanston Police Department records, violent crimes in 2015 were down 5.1 percent overall from 2014, and aggravated battery, aggravated assault, theft and criminal sexual assault all decreased between 2014 and 2015.

The fall in violent crime can possibly be attributed to an increasingly sophisticated data-tracking system and heightened community involvement in reporting crime, said Evanston Police Chief Richard Eddington. He also cited improved outreach efforts from community groups and city officials who have been working to decrease violence at particular properties in the city.

Graphic by Dana Choi and Jerry Lee

Graphic by Dana Choi and Jerry Lee

“You need to step back and look at this entire mosaic of what the city’s doing to address crime and violence,” he said. “It’s not just the cops — there’s a whole department and people committed to reducing the violence.”

A “heat map,” compiled by EPD and released last year, tracked the density of shots-fired incidents from January to July of 2015, and it showed that most of the incidents occur in the city’s west and south sides, namely in the 2nd and 5th Wards, as well as around Howard Street in the 8th Ward.

Ald. Delores Holmes (5th) said although the number of incidents was concerning, not every report of shots fired means a shooting actually occurred.

Eddington said a significant portion of the violent crime in Evanston is generated by two factors: gang violence and a family feud, which Mayor Elizabeth Tisdahl described as similar to the “Hatfields and the McCoys or Romeo and Juliet.”

The feud began in 2005, when 22-year-old Robert Gresham was shot and killed by then-19-year-old Antoine Hill at The Keg of Evanston, which closed in 2013. Since then, Eddington said there have been retaliatory shootings and violence among family members and their affiliates and friends, but that the feud has evolved over time.

“Unfortunately, the conflict has metastasized from just a series of shootings — it’s now added on gang ramifications,” he said. “It’s kind of like we’ve kicked over a can of paint and it’s running everywhere.”

Although the feud is still a factor when it comes to violence in the city, Eddington said neither of this year’s homicides were a result of the feud or any ongoing gang conflicts.

In the past, Eddington said the location of much violent crime could be predicted because feuding parties were often fighting over specific areas of the city. Now, however, Eddington said the “interpersonal” conflict is driven more by individuals who “don’t like each other” instead of being centered around specific locations.

“Now there are these random events … if (those individuals) cross paths, it’s game on,” Eddington said.

Local gun control advocate Carolyn Murray, whose 19-year-old son Justin Murray was killed in Evanston in 2012, said more community involvement was needed in creating a strategic policing plan.

“Basically we’re seeing a lot of crime on Facebook — we’re seeing a lot of threats,” she said. “Police need to know that it is not the same as it was 20 years ago, and I don’t think Evanston has adopted or accepted that they have to change some of the ways they look at things.”

Eddington also acknowledged that social media interaction has further exacerbated conflict between groups in the city.

“The intense emotion is rekindled by just clicking on the Facebook page,” Eddington said. “It’s like the gift that keeps on giving. You know it constantly fuels that angst and that anger and there’s no cooling off period. It’s 24/7, seven days a week.”

Although Eddington said he understands the worry people have about violence, he stressed that crime in Evanston is low, and those not already involved in illicit activity in the city are unlikely to be victims of violence.

Efforts to prevent incidents of crime in the city include trying to decrease the number of guns on the street, as well as increased focus by the community on providing employment opportunities for at-risk youth and young adults. One such initiative is the Mayor’s Summer Youth Employment Program, which helps young Evanston residents find jobs during the summer months when crime tends to spike.

“We’ve been told that if we got to 1,000 jobs, that would have a major impact on the homicide rate,” Tisdahl said. “Eventually, the word on the street will be that jobs are good and people are finding a lot of success having jobs.”

Tisdahl said similar to other cities, a small number of people are responsible for a large number of the problems. She said employment could be effective in directing the 20-30 young people most heavily involved in Evanston crime down a better path.

Although Evanston has taken action to reduce crime, and seen improvements overall, Holmes said she was still frustrated by gun violence in the community.

“We have not had as many deaths that we’ve had in past years. … I can go back to 2010 when we had many more,” she said. “But (even) one is too many.”

Twitter: @noracshelly

Email: [email protected]