Douglas: The ‘Game of Thrones’ rape scene and the boundaries of adaptation

April 24, 2014

In the third episode of season four of “Game of Thrones” (spoiler alert), a female character is raped by a male character. That may sound like something that would happen often in Westeros, the medieval-style land in which the story unfolds, and indeed, it has been intimated, threatened and shown several times already in the show’s earlier seasons. But this time, it was different.

“Why should I care about this abrasively violent scene in an already violent TV show?” you ask yourself.

An understandable query, and in this instance, the answer stems not from the rape culture prevalent on the HBO show (although itself a very disturbing thing), but rather from the risks of “misadaptation.” The speciality in this particular instance of female overpowerment comes from a comparison with the original book.

In the book, the act is consensual.

The book, while allowing for the male character’s first-person point of view in the narration, leaves the reader with, according to the author, George R. R. Martin, a “different impression” than the television show. In the HBO adaptation, however, the woman’s final lines are “It’s not right. It’s not right,” while her male counterpart claims, “I don’t care. I don’t care.” If someone doesn’t say “yes,” it is not consensual. Rape is rape.

But why did the production team feel the need to portray this instance of sexual intercourse as rape? If the story were not based on a book series, this question might deal with the sociological undertones of human nature. However, because it is based on a story from another medium, it is necessary to question the greater problem of adaptation.

In the artistic realm, many projects are inspired by outstanding stories: musicals, novels, films, etc. But to use the phrase “inspired by” does not imply the same faithfulness to the original story that must come when something is adapted. It must be the same story, in a different medium. When a story is adapted, yet differs dramatically from its source material, it is no longer the same story. It can no longer be “based on” whatever it claims to be adapted from.

Understandably, limitations exist in every medium that are not shared in others; in film, it is difficult (impossible? Help me out, Department of Radio, Television and Film) to tell a story from a first person, internal point of view. But to use a limitation to alter the audience’s perception of the characters is unacceptable, because characters are the driving forces of story.

This also has an effect on the contract between an audience and, here, the television show. Because it is no longer the same story when a character has power in one medium and in another has none, the production team has lied to the audience about both the content and the story that appears on the screen.

Even Martin said of his interactions with the production team that they “never discussed this scene, to the best of (his) recollection.” Martin’s lack of say in the process of the retelling of his story is disconcerting artistically because he has lost control over his creations: his characters.

Are the characters the same characters in the television show as they are in the books? Not anymore. When they are altered at all, the adaptation disconnects its discourse with its original source. If adapters aren’t kept from changing characters without consulting the original source’s creator, what is that but theft of intellectual property?

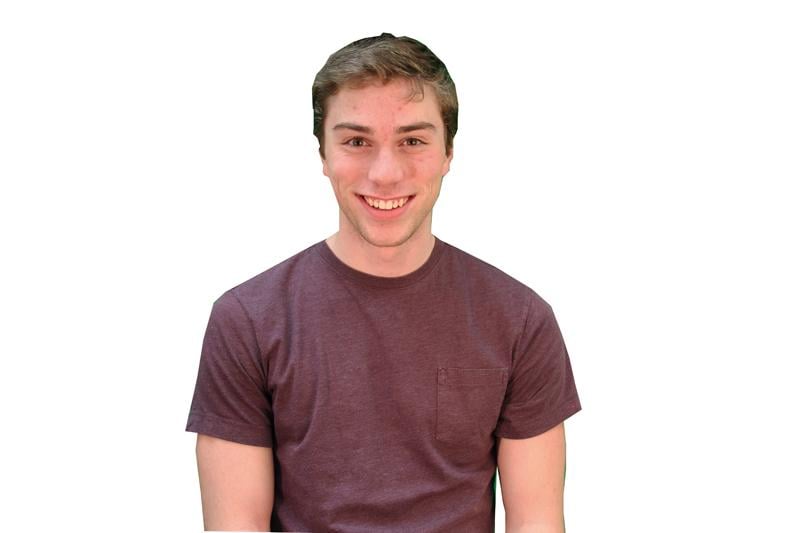

Sam Douglas is a Communication sophomore. He can be reached at samueldouglas2016@u.northwestern.edu. If you would like to respond publicly to this column, send a Letter to the Editor to opinion@dailynorthwestern.com.