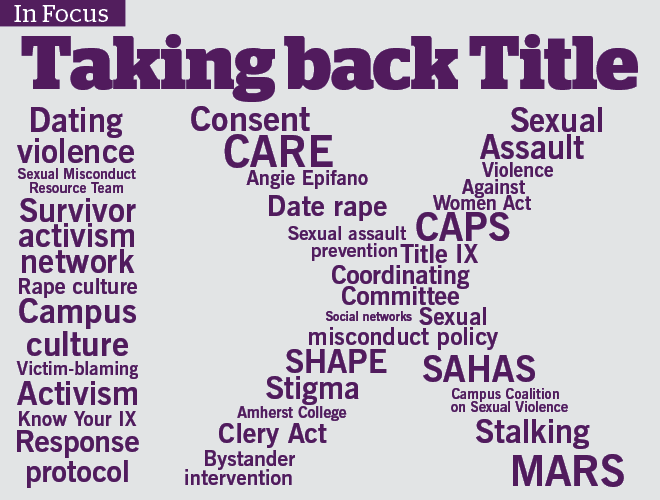

In Focus: Taking back Title IX: Northwestern joins national push to address sexual assault

November 21, 2013

After she was sexually assaulted twice on campus, one Northwestern student felt as though no one understood what she was going through.

The first assault occurred during Homecoming 2012, when her sorority paired with the perpetrator’s fraternity for the weekend’s activities, she said. After the parade, they went to his fraternity house, then to his apartment, where he forcefully tried to remove her pants several times.

This fall, she was sexually assaulted again, this time by a fellow student who knew she was drunk. She woke up to find blood on her sheets.

She considered reporting the rape but decided against it because she did not want to interact with her assailant during the process. She was also afraid her murky memories of the event would “put myself up for victim blaming.”

But she found the opposite attitude this quarter, when she joined NU’s new survivor activism network, a developing group comprising sexual violence survivors and their friends.

“It’s been very helpful to talk to people who understand,” the Medill senior said. “They’re very willing to hear out why you feel the way you do based on your personal experience … and they don’t challenge that.”

The survivor activism group is one of many changes taking place on campus this year. A year after former Amherst College student Angie Epifano’s first-person account of her rape went viral, activists nationwide have combined fighting rape culture with holding universities accountable to federal laws like Title IX, which prohibits sex discrimination and violence in education. At NU, collaboration on a new, more extensive sexual assault policy and other efforts to expand prevention, education and support are coinciding with the ongoing national dialogue.

‘A community in conversation’

After Epifano’s story was published in October 2012 in the school’s student newspaper, students at universities across the country — including Northwestern — began revealing their own experiences with sexual assault.

At the beginning of Fall Quarter 2012, Weinberg senior Lauren Buxbaum had an experience similar to Epifano’s, when the University transported her to a psychiatric ward as she coped with her rape. Buxbaum told The Daily she then felt pressured by administrators to go on medical leave.

In Focus: Amherst Account Inspires Northwestern Student to Reveal Her Own Sexual Assault

According to NU reports, in 2012 only two counts of forcible sex offenses occurred on campus. But from June 2012 to May 2013, 54 students went to the Center for Awareness, Response and Education.

CARE, established in 2011, provides education and advocacy for students affected by sexual assault, dating violence and stalking. But many say there is still a need for more sexual violence resources on campus. The new survivor group — and a push to alter University policy — represent “proactive” efforts to do so, said Laura Stuart, coordinator of sexual health education and violence prevention.

“I’m glad that we have been a community in conversation because it’s what we should be doing,” she said.

Characterizing consent

A more detailed definition of consent for sexual activity is a major component of NU’s new sexual assault policy, due to roll out January.

Both Stuart and Eva Ball, coordinator of sexual violence response services and advocacy, stressed the importance of specifying what constitutes consent, especially because most victims know their attacker.

“Having it clearly defined, to say that consent needs to be something that is actively, presently given — it’s not just the absence of a ‘no,’ it’s the presence of a ‘yes,’ one way or another — is going to be a game-changer on this campus,” Ball said.

Despite long being touted as the necessary gateway to sexual activity, consent has been noticeably neglected in sexual assault policies. Although both Illinois state law and current University policy mention consent and penalize acts committed without it, the term itself is not defined.’

Providing a definition is a “huge turning point” that will allow victims to better recognize their own rights when reporting sexual assault, Ball said.

“I see so many students who come into my office, and they tell me their experience, and it is clear to me by Illinois definition, by NU policy definition, they just described sexual assault,” she said. “But because of our common conception of what sexual assault looks like, they don’t feel entitled to call it that themselves, and they often blame themselves.”

For the Medill senior, being able to label her assault “was a really empowering experience.”

“Having people understand what consent really means was huge for me because they would back me up and be like, ‘No, what happened was rape or was sexual assault,’” she said. “(It) made me feel less like I had made it up in my own head.”

A University-approved definition would also further validate the efforts of groups like CARE, Sexual Health and Assault Peer Educators and Men Against Rape and Sexual Assault to educate students about the boundaries of sexual behavior.

Empowering survivors

Being a sexual assault survivor can be “pretty isolating,” the Medill senior said.

When she told friends about her first experience with sexual assault, many were supportive, but some dismissed it. Other friends might be sympathetic toward her situation, she said, but they forget to be sensitive when she feels uncomfortable going to a party.

“They need to remember that rape is something that happens, and it’s going to affect this person in a whole bunch of different ways,” she said

Joining a group composed of survivors — a significant new sexual violence resource at NU — has given her a network of people who, at the very least, understand her experience.

“There’s so many things that tie back to survivor identity,” she said. “It’s pretty hard to gather unless you have the personal experience and have felt it influence so many different areas of your life.”

In a statement, the currently untitled activism network asserts it is not a support group and that it intends “to work with the University and other campus programs to appropriately craft their messages/programs/actions regarding sexual violence.”

“There’s not a group that’s focused on survivors,” the Medill senior said. “There’s a lot of groups that’s focused on prevention, but there’s not a lot of focus on ‘after CARE.’ It’s very much about taking proactive steps. We’re just trying to figure out how.”

Because the survivor advocacy group does not want to pressure its members to participate in activism that may trigger memories of their attacks, attendance at the survivor advocacy group varies from about three to 10 students per meeting. Membership is currently anonymous.

Although activism will be a key feature of the group, its form is yet to be determined.

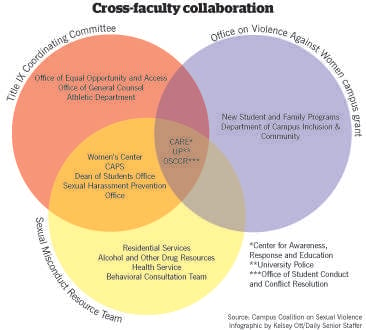

A new survivor support group is also taking form at the administrative level. Ball is heading up the Sexual Misconduct Resource Team, a coalition of University offices that will convene quarterly to examine the quality of survivor care and resources on campus. The group will hold its first meeting in December.

SMRT combines offices like CARE, University Police, Health Service and the Dean of Students office, with those less directly involved in sexual assault issues, like Counseling and Psychological Services, the Behavioral Consultation Team and Alcohol and Other Drug Resources.

“I want it to be, at the very least, a group that helps professionals on campus have continuity of care, make sure that we’re giving uniform messaging to survivors, make sure that all survivors are being referred to CARE and know their rights,” Ball said.

CARE is also redesigning its website to make it more survivor-focused. That, along with the survivor group and SMRT, represent a school-wide shift toward prioritizing victims of sexual assault and supporting them with as many resources as possible.

“A lot of times the survivor viewpoint gets forgotten,” the Medill senior said.

Prioritizing stalking, dating violence

The new policy will not only be more detailed but also more expansive, with an extensive section devoted to stalking and domestic and dating violence.

“It basically covers all types of potential abusive relationships,” said Frances Fu, a member of SHAPE and the Campus Coalition on Sexual Violence.

At an early November meeting of CCSV, a network of administrative and student groups involved in sexual assault issues, Stuart described the new policy’s drafted definition of stalking as unwelcome conduct making an individual fear for his or her safety or that of a third party, or cause other emotional distress.

Fear is a key component of the definition. The stalking policy may be difficult for people to understand because it sometimes “criminalizes things that aren’t otherwise criminal,” like sending excessive Facebook messages. Such behavior, Stuart said, may appear ordinary but when targeted at a specific person can compromise his or her personal safety.

“Stalking is especially a problem on college campuses because there’s a lot of students in a confined place, so there’s more reason and opportunity for two people to randomly bump into each other,” said Fu, a SESP junior.

Student input from groups like College Feminists, SHAPE and MARS have influenced the policy’s wording to be less confusing and more accessible, she added.

“They all kind of go hand-in-hand,” the Medill senior said of sexual assault, stalking and relationship violence. “They do all work together, and they all are acts of control and power, which is really what rape is about.”

Broadening CARE’s scope

CCSV meets with interested students and community members each month in Searle Hall to discuss the state of campus policies and programs related to sexual assault.

Formed in May 2010, CCSV reports its findings annually to the vice president of student affairs. Initially, one of CCSV’s main duties was establishing CARE in 2011 and examining its services. More recently, it has been advising the Office of Student Conduct and Conflict Resolution on the new policy.

At the CCSV meeting, Stuart announced NU is re-applying for a grant from the U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women. The original $300,000 grant, which runs out in the fall of 2014, funded the establishment of CARE, created Ball’s job and increased sexual assault education and prevention training on campus.

The CCSV is also requesting a reallocation of current funds to develop a new educational program with the Center for Contextual Change, a nonprofit victim service organization in Skokie. The center joined CCSV in March, and, if funded, the partnership would create an educational program aimed at students who show signs of violating the sexual misconduct policy.

Stuart tentatively suggested at the meeting that NU could potentially refer students who have been accused of sexual violence to the Center for Contextual Change, or students themselves could refer friends who they are concerned will violate policy.

Stuart and Lance Watson, assistant director of student conduct and conflict resolution, who are in charge of planning and development for the program at NU, said it would be unique in one critical regard — providing services to the accused instead of the victims.

“For decades in the United States we’ve been talking about victims and how to support victims,” Ball said. “But since the research on perpetrators is pretty conclusive that most perpetrators offend multiple times, in my mind if we can stop one perpetrator from re-offending, we can stop multiple people from becoming victims or survivors.”

Localizing a national fight

“No one should ever feel unsafe at their school.”

That was Epifano’s message for NU when she spoke on campus last month, highlighting the national movement around fighting sexual assault. Her visit was timely, with alterations to NU’s policy drawn from input on campus and national standards.

The new guidelines come amid a storm of activism on college campuses across the nation, as students file complaints against universities claiming they mishandled or misreported sexual assault. Under the 1990 Clery Act, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which prohibits sex discrimination in education (including sexual harassment and violence), and the April 2011 Dear Colleague Letter issued by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights that details universities’ responsibilities complying with Title IX, schools must report all instances of sexual violence on their campuses and provide safe environments for survivors to report assaults, seek help and continue their studies.

On Nov. 14, Title IX complaints were filed against Vanderbilt University and Amherst College with the help of Know Your IX, a national organization recently founded by survivors and advocates to fight sexual assault on college campuses. In the past year, complaints have been filed against many other universities, including the University of North Carolina, Swarthmore College, Dartmouth College and the University of Southern California. The Know Your IX group provides information on how to file complaints, and its educational website launched almost four months ago to inform students about their rights.

“It’s timely,” said Dean of Students Todd Adams. “All campuses are looking at this issue very closely right now, and if they’re not, they should be.

NU’s policy changes would keep the University compliant with federal law according to Title IX and the March reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act. The University had already been looking to revise its sexual misconduct policy, and the VAWA reauthorization served as another reminder of federal standards, Adams said.

The Campus Sexual Violence Elimination Act provision of the VAWA reauthorization requires universities to incorporate stalking, domestic violence and relationship violence into their crime reports.

To better follow the guidelines set forth in the Dear Colleague Letter, this spring Joan Slavin was designated the University’s official Title IX coordinator, a position she held in interim since 2011.

Slavin’s position “better enables us to provide centralized leadership in addressing and preventing sexual harassment, sex discrimination, and sexual violence at Northwestern under federal, state, and local laws and regulations,” she wrote in an email to The Daily.

Slavin is also the director of sexual harassment prevention at NU and heads up the recently formed Title IX Coordinating Committee, which includes CARE, the Dean of Students’ office, the Sexual Harassment Prevention Office, the Women’s Center and other administrative groups involved with sexual violence issues.

Over the summer, the committee launched a Title IX page on the Office of the Provost website that compiles information about the law and NU’s statement of compliance.

“The law has been constantly evolving in the area of sexual misconduct, stalking, and domestic and dating violence, and we want to make sure our policies and practices are state-of-the art in these areas,” Slavin said.

Timeline: Northwestern, universities respond to sexual violence

Timeline JS by Cat Zakrzewski/Daily Senior Staffer

Changing campus culture

Despite many changes on campus, challenges remain in creating a safe environment.

MARS co-programming chair Gabe Bergado, a Medill senior, said he hopes to see the dialogue about sexual assault expand further.

“There needs to be other things addressed,” Bergado said. “I was really interested in sexual violence within the LGBTQ community, and that’s definitely something that’s left out of the conversation a lot.”

Even beyond addressing specific topics of conversation, amending a policy and creating new groups may not be enough to create a cultural shift.

The VAWA reauthorization requires ongoing education about sexual assault for all students and faculty.

“That is a huge challenge,” Ball said. “We’re making progress, we’re talking about it, we’re looking into different educational programs, and I have no doubt that we will implement that to the best of our ability as soon as we can.”

It is both difficult and important to uphold not only the “letter of the law” when it comes to complying with Title IX and VAWA, but also the spirit of the law, Ball said. Providing educational programs might not help if they are viewed as “this thing we have to do.”

“We’re biting off as much as we can chew,” she said. “But ultimately we need buy-in from every corner of campus to make effective culture change on this campus.”

Without campus-wide participation in a dialogue about sexual assault, current activism and advocacy seems like preaching to the choir, the Medill senior said

“There has to be some sort of intervention on the University’s part to somehow get everyone involved in a conversation,” she said. “If somebody doesn’t mind taking advantage of a drunk girl, they’re probably not the kind of person that’s going to go to an awareness event.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @jeannekuang