Andres: A century after his birth, Otto Graham is given too little credit for revolutionizing football

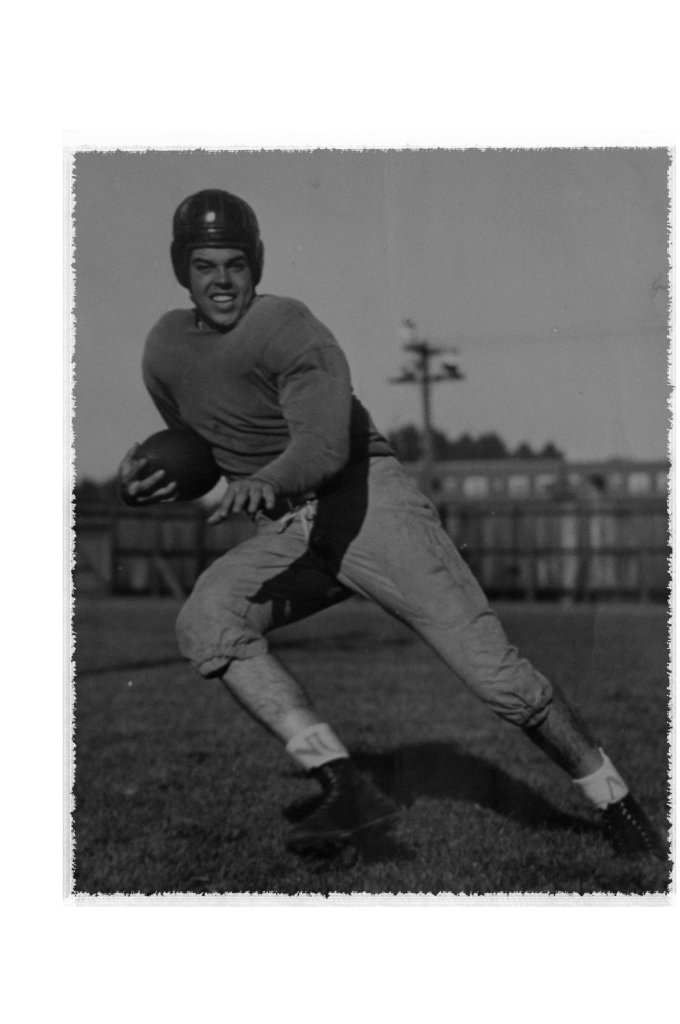

Otto Graham at Northwestern. Graham, born 100 years ago today, revolutionized pro football with his passing for the Cleveland Browns.

December 6, 2021

In any country that has its sporting priorities straight, a man who played the most popular sport’s most visible position and won 81% of his games would be an icon. A man who altered the way that sport is played would be a hero. A man who played in a championship game every season of his 10-year career would be immortal.

Other nations have the right idea. Brazil has designated Pelé, who played soccer with a creativity not seen before or since, as a national treasure. Canada worships hockey’s Wayne Gretzky and Australia venerates cricket’s Donald Bradman — both record-breaking maestros who elevated their sports.

Such name recognition has largely evaded Otto Graham, the two-sport Northwestern star born 100 years ago today in Waukegan, Ill. who went on to win seven pro football championships with the Cleveland Browns. This is wrong, and few oversights in sports are more glaring.

Among the NFL’s great quarterbacks, Tom Brady, Peyton Manning and Joe Montana worked their wonders within living memory. Johnny Unitas has the mystique of 1958’s “Greatest Game Ever Played” and the long-dead Baltimore Colts behind him. Even Sammy Baugh, Washington’s gunslinger during the Great Depression, gets credited as the first modern passer.

But the same factors that help other quarterbacks’ reputations work against Graham. “Automatic Otto” is dead, as are most fans and writers who watched him. Pro football was a distant second in popularity to college football when he played, and unlike Baugh at TCU, he didn’t vacuum up hardware at NU (apart from an All-America selection) to make up for it.

And while Cleveland was a big market during Graham’s tenure — the seventh-largest city in the country when he guided the Browns to the 1950 NFL title, in fact — it shrunk considerably in the decades after he left.

This leaves football’s fans and amateur historians to pass on Graham’s legacy. And what a legacy it is.

When coach Paul Brown took charge of Cleveland’s new All-America Football Conference franchise in 1945, he moved quickly to sign Graham, whose Cats had beaten Brown’s Ohio State team in 1941. It was a perfect marriage: a coach at the vanguard of contemporary football innovation, and a versatile quarterback to run his system.

Even Brown or Graham, however, could not have imagined the success that awaited them. In 1946, the Browns went 12-2 and won the AAFC title. In 1947, they fared even better, going 12-1-1 and winning it again. In 1948, they somehow improved on that, winning all 14 games and their third straight championship. 1949 brought more of the same: a fourth title in four years.

And Graham’s Browns didn’t just win. They won with a passing offense light-years ahead of their AAFC and NFL peers. The inaugural 1946 Browns averaged 30.2 points per game, tallying over 100 more than the league’s second-highest scoring team. They scored 40 or more points at least twice in each of their first four seasons, while Graham took a turn leading the league at least once in every major passing category.

The Browns won with such frequency that the AAFC was soon insolvent, and merged into the NFL in 1950. Cleveland, the San Francisco 49ers and an early version of the Colts joined the new league. NFL power brokers regarded the AAFC as inferior, but couldn’t resist matching the Browns up against the 1949 NFL champion Philadelphia Eagles in the first week of the 1950 season.

At 3:30 of this NFL Films clip from that ballyhooed first game, the revolution begins to take shape. Graham, wearing No. 60, takes the snap and drops back, back, back, retreating almost 10 yards from the grainy, black-and-white mass of humanity. He flings the ball downfield to halfback Dub Jones, who catches it in stride, keeps his feet and races into the end zone with a 59-yard score.

Two more Graham passing touchdowns and 346 passing yards later, the Browns were 35-10 victors.

Graham and the Browns continued their high-flying ways in the “big league.” It was in the NFL, not the AAFC, that “Automatic Otto” established most of his career bests: in completions and yards (1952) and in completion percentage and yards per attempt (1953).

A strong, stable core made up of running back Marion Motley, wide receiver Dante Lavelli, kicker-tackle Lou Groza, and others supported Graham en route to three NFL titles: a last-second 30-28 win over the Los Angeles Rams in 1950, a 56-10 beatdown of the Detroit Lions in 1954 and a virtuoso 209-yard performance in his final career game against the Rams in 1955.

Times have changed in the 66 years since Graham’s retirement. The NFL and its players have gotten bigger and more physically gifted. The wide-open passing attack Brown once championed is now everywhere, with teams scraping the 30s and 40s every week.

The Cats quarterback who made it all possible is worth a Google search, and a mention among the most transformative athletes in American history.

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated Otto Graham’s birthplace as Waukegan, Wis. Graham was born in Waukegan, Ill. The Daily regrets the error.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @pandres2001

Related Stories:

— Football Notebook: Six Northwestern players in transfer portal

— Football: Tight ends coach Bob Heffner retires after 13 years at Northwestern

— Football: Northwestern concludes 2021 season with first loss to Illinois in seven years