The “very radical stance”: A history of women’s suffrage in Evanston

November 3, 2020

On Aug. 18, 1920, the 19th Amendment, which granted American women the right to vote, became the law of the land. The real timeline of women voting in Evanston is a little more complicated.

Decades before the amendment was ratified, Illinois women, led in part by Evanston residents, started voting on “partial ballots” masterminded through a series of legal loopholes. Lori Osborne, director of the Evanston Women’s History Project at the Evanston History Center, said the move pressured other states into following suit.

Some scholars say racism within the movement tainted the fight for the vote, with leaders like Woman’s Christian Temperance Union president Frances Willard accused of leaving Black women behind in their activism.

Over the past century, Evanston women have continued pressing for voter education and participation. Now, they’re mobilizing the vote in advance of Tuesday’s election and looking back at the legacy of the women who propelled them to the polls.

“No one wants only Illinois women voting for president”

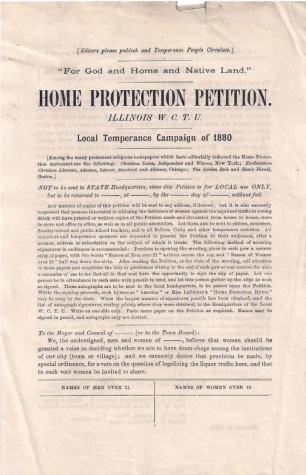

In the late 1870s, Willard started pushing for a “Home Protection” ballot to allow women to vote on issues pertaining to their traditional roles as wives and mothers.

Her ballot, which was incorporated into the 1879 Hinds Bill, aimed to let women vote on decisions affecting children and family life, like school policies and the sale of alcohol, Osborne said.

“Even up until the last minute, suffrage was very radical for women,” Osborne said. “To be involved in suffrage was still, even in those late days, considered a very radical stance.”

So, Osborne said, women wedged their way to the polls with a demand men couldn’t possibly question: the chance to vote and run for their school boards.

The Hinds Bill didn’t garner enough votes in Springfield to pass into law, but the idea stuck. By 1892, women were voting in Evanston school board elections. Two women ran for seats. One of those women, Louise Brockaway Stanwood, won.

“This partial ballot is such a key thing, and Illinois is at the center of this experiment,” Osborne said. “It gains women credibility, it gives women experience being informed voters, it gives them experience being active in their towns.”

In 1913, Illinois women gained another set of partial ballots that enabled them to vote for presidential electors, and by 1916, they were officially voting in presidential elections.

Illinois wasn’t the only state to grant women the right to vote in that presidential election, but it was the largest, Osborne said. Threatened by Illinois’ burgeoning political power, other states like New York quickly followed its example.

“That is why it only takes three more years for that 19th Amendment to pass, in my opinion,” she said. “No one wants only Illinois women voting for president.”

Wells condemns Willard’s racism, Black women press for the vote

Ida B. Wells, a Chicago civil rights leader and journalist known for her anti-lynching work, founded the Alpha Suffrage Club in January 1913 and took to the nation’s capital to protest alongside the Illinois delegation. Wells operated through an intersectional lens, tying her fight for the vote with her fight for racial justice and condemning Willard for her failure to lead against issues of racism, Osborne said.

The temperance movement, which advocated a ban on alcohol consumption and distribution, was a key motivator for many Evanston women fighting for suffrage, especially Willard. Scholars say Willard often courted Southern White women to drum up support for temperance at the expense of the movement for racial justice.

In an 1890 newspaper interview, Willard used racist language drawing upon anti-Black stereotypes to make a case against taverns. Four years later, Wells republished the interview and urged Willard to take a stand against lynching. In 1895, the WCTU published an anti-lynching resolution.

With Wells leading the movement in Chicago, Black women in Evanston were also actively pushing for suffrage, and could vote on partial ballots. However, many local Black voices and stories were lost to history, Osborne said.

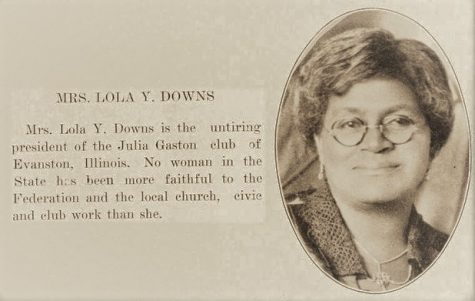

Most of Black women’s activism took place through organizations like the Ladies Colored Republican Club of Evanston, a political group involved in the suffrage movement, or the Julia Gaston Club, a women’s club in Evanston. Local leaders like Lola Downs and Celia Webb Hill, Julia Gaston Club presidents, often tied their fight for suffrage with their work in the church.

A century later, women still fight

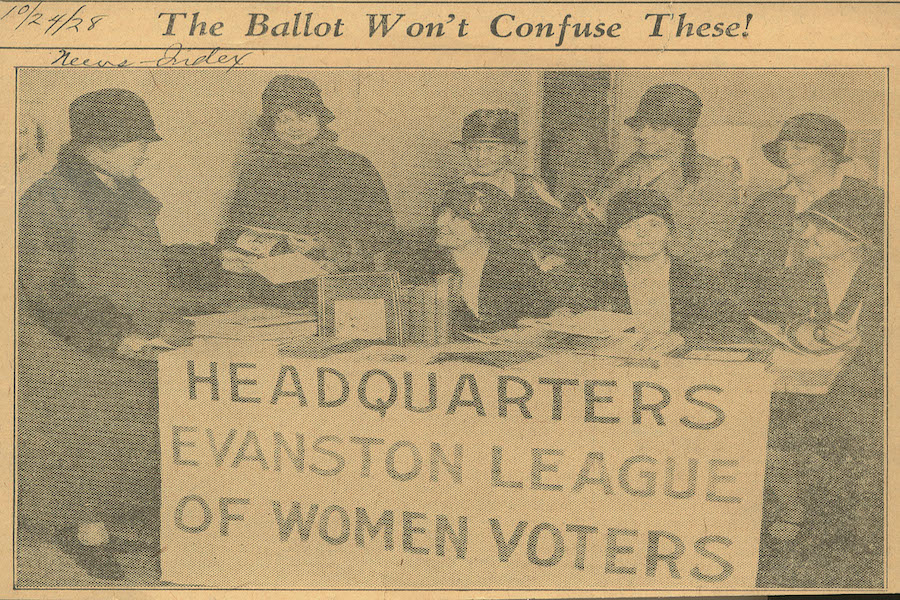

After the passage of the 19th Amendment, local suffragists formed groups like the League of Women Voters of Evanston to encourage voter education, registration and turnout. Others set out to work on the Equal Rights Amendment, which was proposed in the early 1920s.

Betty Hayford, a current LWVE board member, said when the League was founded in 1920, women had the right to vote, but many women weren’t used to thinking about it. As a result, the organization made a point to educate women voters — a mission it continues today.

Today, the League continues its outreach by talking with voters at registration events throughout the city and publishing information to educate voters on candidates, the voting process and voters’ rights.

While the pandemic has forced the LWVE to innovate its outreach strategies, Hayford said the League has carried on its operations both in-person and online.

“I think the greatest barrier to voting at the moment is lack of information,” Hayford said. “That’s an ongoing challenge.”

Democratic Party of Evanston member Kemone Hendricks, who founded Evanston Present and Future and the city’s Juneteenth Parade, has led a voter registration pop-up initiative throughout the city and at local Black-owned businesses.

Osborne said she is not aware of documented cases of voter suppression specific to Evanston’s history. But voter suppression, Hendricks said, takes many different forms, many of which originate at the national level.

Strict voter identification requirements, for example, pose a challenge to people who don’t have the money to update their IDs, Hendricks said. Additionally, she said discouraging voting by mail could deter people with disabilities and people without access to transportation from casting their ballots.

“A lot of the issues is not local,” Hendricks said. “It all trickles down locally…You can’t be in denial about that.”

Other issues local to Evanston voting, she said, include a lack of presence from local officials and the location of Evanston’s ballot dropbox, which could be out of the way for some residents living in south Evanston.

Hendricks said she knows some community members face disillusionment about their choices in the upcoming presidential election. However, she said it’s still crucial to vote to honor the right for which their ancestors fought and sacrificed. Hendricks said she considers the suffrage movement an ongoing struggle — not one that ended definitively on Aug. 18, 1920.

“What the 19th Amendment means to me is what July 4th means to me,” Hendricks said. “It just reminds me of the struggle we’ve been through as a Black community, and how we continue to be overlooked by well-meaning White people. In order to move forward as a whole community, we have to re-evaluate all of these milestones … and celebrate them for what they should have been. That’s how you implement change.”

Email: maiaspoto2023@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @maia_spoto

Related Stories:

— I’ll drink to that: A history of alcohol and temperance in Evanston

— Women’s suffrage exhibit highlights 19th Amendment, beyond

— Frances Willard House Museum discusses relationship between Willard and Ida B. Wells