Memorial for a Mother

Natasha Trethewey honors her mother Gwen in new memoir “Memorial Drive”

October 14, 2020

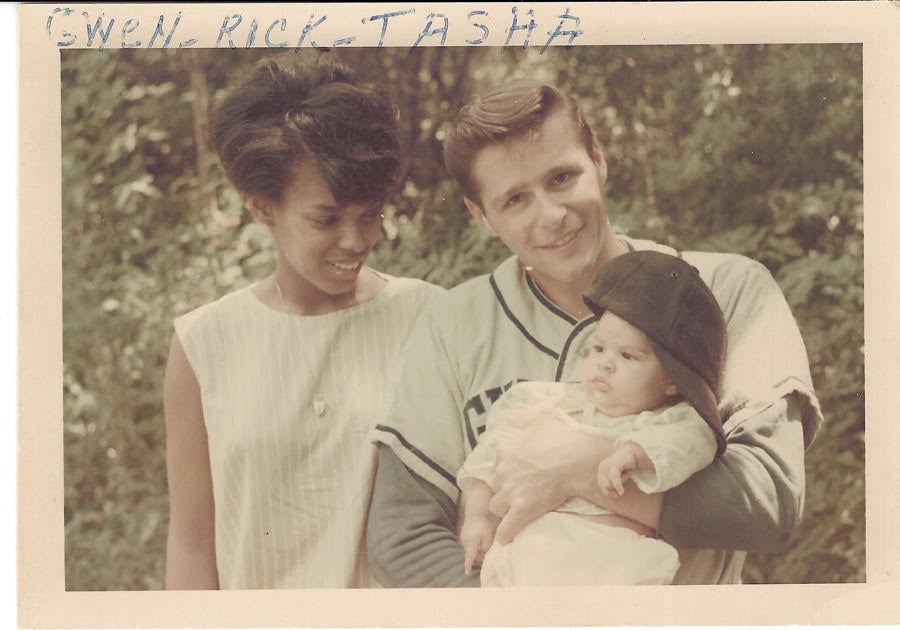

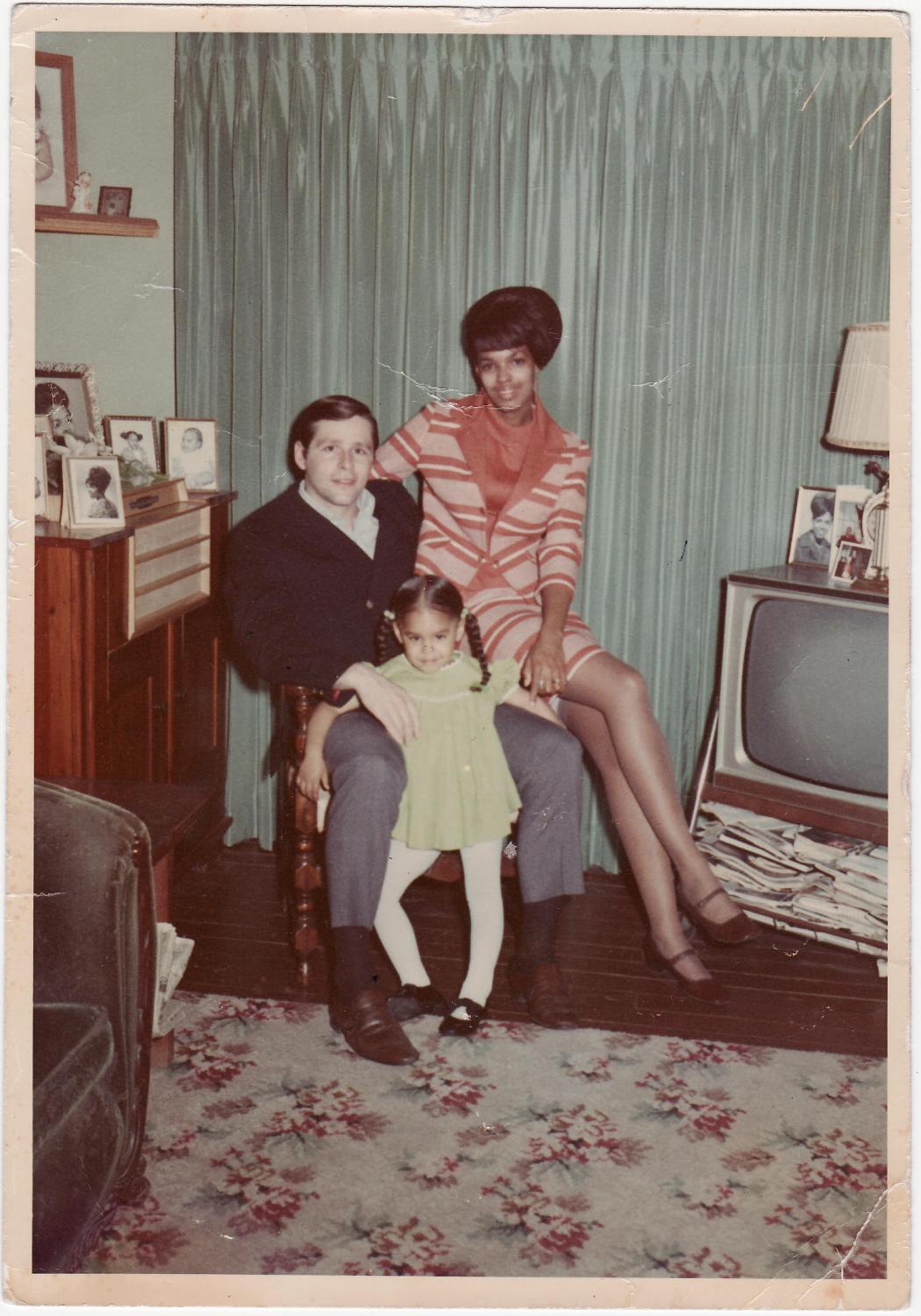

The Monthly

One of the most devastating passages of Natasha Trethewey’s “Memorial Drive” arrives halfway through the memoir, in the chapter “You Know.” After 80 pages describing Trethewey’s early life — her birth to a Black mother and a White father, her childhood growing up as a biracial girl in late 60s Mississippi, her parent’s eventual divorce, her move to Atlanta with her mother, her mother’s second marriage to another man — in the first person, the book makes a sudden shift to second person, describing the experiences Trethewey went through as occurring to “you.”

The chapter tracks Trethewey as her family moves to the suburbs in 1976, and she slowly grows aware of the abuse her stepfather Joel is inflicting on her mother Gwen. At one point, she tries to tell her fifth grade teacher that she heard her stepfather beat her mother the night before, only to be told that “sometimes adults get angry with each other.” The chapter ends with Trethewey writing “Look at you. Even now you think you can write yourself away from that girl that you were, distance yourself in the second person, as if you weren’t the one to whom any of this happened.”

Trethewey said she wrote the chapter in the second person to comment on how trauma divides people, fundamentally altering them from the person they were into the person they are afterwards. It also acts as a reflection of her own coping devices, on how she has shied away from confronting the traumas of her childhood for years.

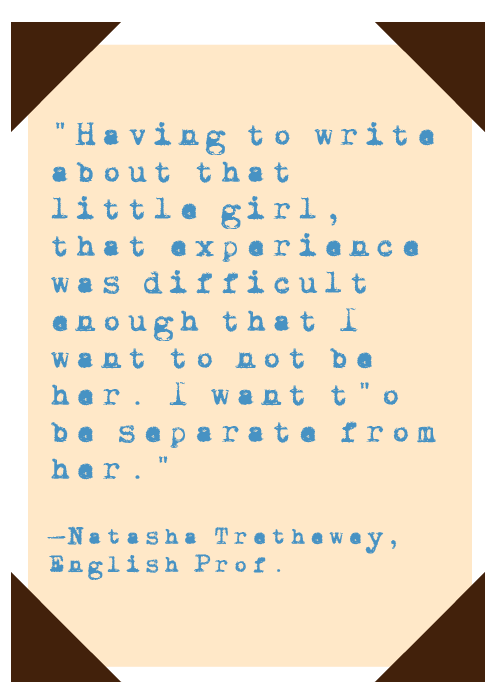

“Having to write about that little girl, that experience was difficult enough that I want to  not be her,” English Prof. Trethewey said. “I want to be separate from her. So to stand aside and write in a direct address to her, both echoes how I feel even now and attempts to enact in the writing what the division of self is like. But once I get to that, I realized I was faced with a different sort of dilemma. Now that I had split the self from the former self, I had to become unfragmented and become whole again.”

not be her,” English Prof. Trethewey said. “I want to be separate from her. So to stand aside and write in a direct address to her, both echoes how I feel even now and attempts to enact in the writing what the division of self is like. But once I get to that, I realized I was faced with a different sort of dilemma. Now that I had split the self from the former self, I had to become unfragmented and become whole again.”

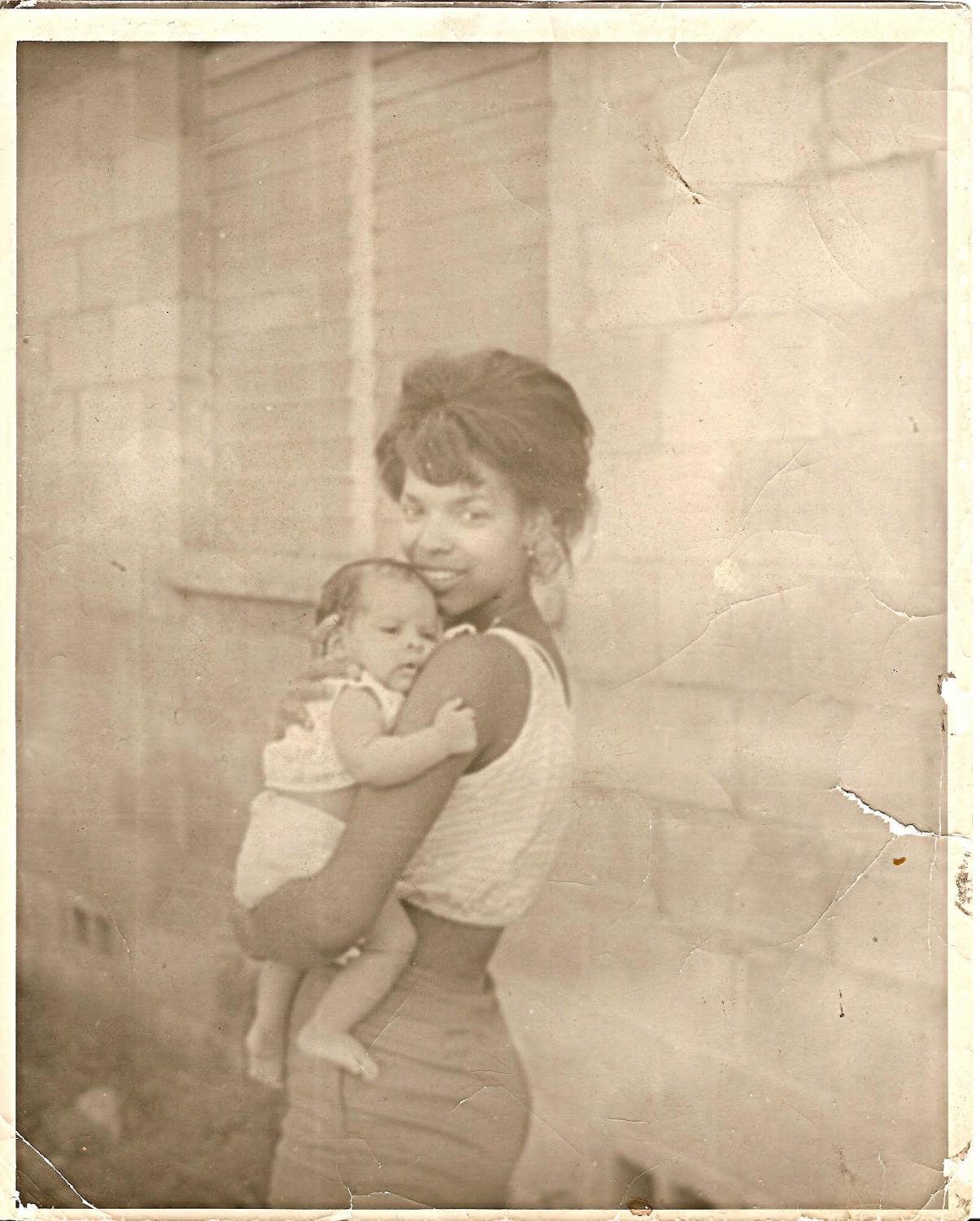

On June 5, 1985, when Trethewey was a 19-year-old undergraduate at the University of Georgia, Joel shot and murdered Gwen, who in the intervening years had fled their marriage and divorced him. “Memorial Drive” explores both Trethewey’s memories of her mother and the writing of the book itself decades later, as she examines the impact the tragedy had on her. It’s a devastating read, but also one filled with love, in its portrayal of her mother’s life.

“Memorial Drive” isn’t the first work Trethewey wrote that honors her mother; the first poem Trethewey created as an adult was written not long after her mother died, as she tried to make sense of the tragedy. Many of the poems that compromise “Native Guard,” her 2006 collection that won the Pulitzer Prize in 2007, focus on the memory of Gwen.

But the memoir was the most emotionally difficult work she ever created, taking her seven years to complete. She stopped and started writing several times, continually revising the opening chapter focusing on her childhood in Mississippi in order to avoid confronting the trauma of the later material. Even now after writing the book, the events are still hard for her to talk about; during our interview, she choked up describing the way that the bullet went through her mother’s hand.

Once Trethewey began writing the book, however, she found that many of the memories of her childhood she most wanted to forget were still with her. The book is filled with details and scenes of her childhood that are devastating in their power and simplicity; one dinner scene, where Gwen raises her voice at Joel and Trethewey thinks to herself that her mother will be beaten later for it, is short but vivid in the ways it captures every person’s body language and actions, and how it portrays the strength of the love between mother and daughter.

Trethewey primarily works as a poet, and “Memorial Drive” reads like prose as poetry, filled with lyrical passages and memorable symbols that recur throughout: the bullet hole Joel left in the apartment wall, Trethewey’s birthmark on the back of her thigh, a recurring scene of her nearly drowning in a pool as a child. To transition between poetry to prose, Trethewey leaned into the similarities she found between the mediums, using silences and pauses in the book in the same way she does in her poetry and using the natural rhythms of language and syntax to inform her prose style. During the writing of the memoir, Trethewey would start writing passages that would later develop into individual poems; some of these poems were later included in her 2018 collection “Monument: Poems New and Selected.”

“I sort of thought of the book as an extended poem,” Trethewey said, “circling back on itself, using motifs that appear throughout, threads that I pull through the entire book like I pull through an entire collection.”

In addition to Trethewey’s prose, the book also makes liberal use of official police records from the murder case, which Trethewey obtained from the first police officer on the scene of the crime after she met him by chance in 2005. Before the murder, Joel had made a previous attempt on Gwen’s life, so she filed a police report and had her phone wiretapped. The transcript of a call between Gwen and Joel in which Joel repeatedly threatens to kill her is reproduced toward the tail end of the memoir; even with Trethewey making edits to shorten it, the transcript goes on for an agonizing 27 pages. As difficult as it is to read, it’s also a moving portrait of Gwen, portraying both her kindness and her strength as she handles the emotional turmoil of the situation.

“The entire book is extraordinarily generous in how much it shares with the reader,” said Rachel Webster, an English prof. who works with Trethewey in the creative writing department. “She lets us get to know her mom on the page, and she lets us see herself as a girl. There’s something very, very generous about letting us see (the raw transcripts), which is probably the most tender and intimate thing she could let us see. All of us who have been around mental illness and have seen violence in families, there’s a lot of recognition in that, and there was something very healing about seeing that honestly.”

Although “Memorial Drive” acts as an intimate look at Trethewey’s life, it also positions itself as part of a larger story of the historical marginalization and erasure of Black women in America, and the history of Black people in the South. In the opening prologue, Trethewey describes returning to the site of the murder nearly 30 years after the fact, and draws the contrast between how all evidence of her mother’s life is gone and the fact that the apartment building is located on the street (the titular Memorial Drive) that leads to Stone Mountain, the largest memorial to the Confederacy in the United States. Trethewey also notes in the chapter describing her early childhood that her birth, as a child of an interracial marriage that was still illegal in the state she was born in, occurred on Confederate Memorial Day. Late in the book, a short, page-long chapter states that the official record of Gwen’s death gets the date wrong, erasing five days from her life. The day Joel shot Gwen, the police officer assigned to watch over the apartment left in the early morning in spite of being ordered to stay, his negligence causing her death.

For Trethewey, her interest in the theme of Black erasure in part stems from growing up in Mississippi, where she felt surrounded by narratives of the Confederacy and White supremacy. In “Native Guard,” she writes about Fort Massachusetts, a historic military base near her hometown that was manned by Black Union soldiers during the Civil War. On the island the fort is on, for many years there was no mention of these soldiers; instead, there were Confederate monuments. The title poem of “Native Guard” honors those Black soldiers, bringing light to stories that the United States often neglects to tell.

Trethewey’s friend and School of Communication Dean E. Patrick Johnson, who has worked with her on the school’s Black Arts Consortium, says these themes speak to modern problems surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement, and how Black women’s issues are ignored and neglected. He pointed to how long it took for Breonna Taylor’s death to gain public notice compared to her male counterparts as an example of how Black women are forgotten and failed by the general public.

“It speaks to a larger issue of how Black women’s contributions and lives, they have not been at the forefront,” Johnson said. “Even in African-American history, many of the women who were a part of the Civil Rights Movement, the anti-lynching movement, they were overshadowed, even though they were in many cases at the forefront of those movements.”

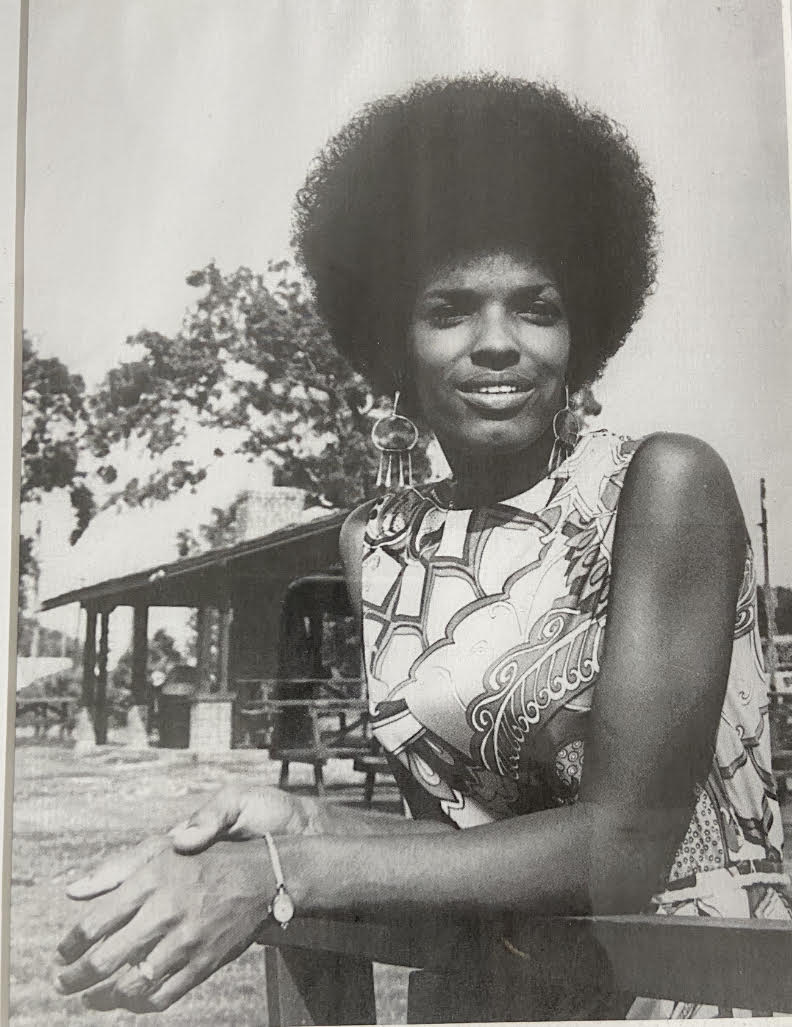

Trethewey said as emotionally difficult as the book was to write, she also felt it was something she needed to create, both for herself and for her mother. Whenever Trethewey made strides in her poetry career, such as winning the Pulitzer or when she was appointed United States Poet Laureate, she noticed that people wrote about her career and her backstory by focusing on her father, a poet and professor, and the impact he had on her. For the writers behind these pieces, it was easy to draw a straight line from Trethewey’s White parent and his poetry to her career, and reduce her Black parent to a footnote — a murdered woman. “Memorial Drive” acts as a necessary corrective towards that simplistic narrative, to ensure Gwen would never be forgotten.

Trethewey said as emotionally difficult as the book was to write, she also felt it was something she needed to create, both for herself and for her mother. Whenever Trethewey made strides in her poetry career, such as winning the Pulitzer or when she was appointed United States Poet Laureate, she noticed that people wrote about her career and her backstory by focusing on her father, a poet and professor, and the impact he had on her. For the writers behind these pieces, it was easy to draw a straight line from Trethewey’s White parent and his poetry to her career, and reduce her Black parent to a footnote — a murdered woman. “Memorial Drive” acts as a necessary corrective towards that simplistic narrative, to ensure Gwen would never be forgotten.

“I felt she was being erased, and she wasn’t understood as the reason I am a writer,” Trethewey said. “So as difficult as it is to talk about the details, I am happy that there are people who are reading the book and listening and knowing some things about the loveliness and the brilliance of my mother. That she’s not simply that footnote.”

Read more from The Monthly: October Edition here

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @wilsonbchapman

Related Stories:

— NU alum and ‘Divergent’ author Veronica Roth premieres first novel for adults

— Q&A: Prof. Celeste Watkins-Hayes talks about new book “Remaking a Life”