Fighting for liberation for 50 years: Maher Ahmad remembers his time with the Gay Liberation Front

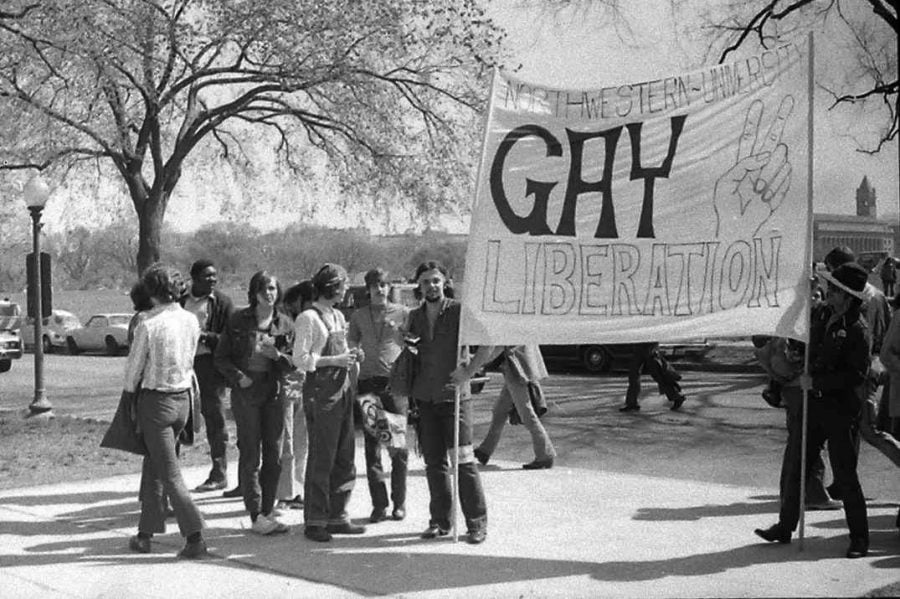

In 1970, the Gay Liberation Front sent a contingent to march on Washington in protest of the Vietnam War.

July 28, 2020

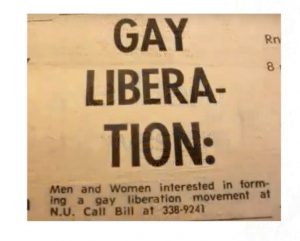

During Maher Ahmad’s (Communication ’71, ’74) junior year on campus, he saw an advertisement in The Daily Northwestern that would redefine queer culture on campus. It said, “GAY LIBERATION: Men and Women interested in forming a gay liberation movement at N.U. Call Bill at 338-9241.”

Ahmad soon dialed the number, and the two men unofficially began the Gay Liberation Front — Northwestern’s first gay rights advocacy group and what is now known as the Rainbow Alliance.

The year was 1970, and revolution was in the air.

That same year, student protests took place on NU’s campus as students voiced their disapproval in the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War. In 1964, the Free Speech Movement gained traction across the country as college students demanded that schools stop restricting their free speech rights. And In 1969, revolutionary riots erupted at the Stonewall Inn when police raided a gay club in New York City.

“This whole desire to throw off the strictures of the system… that was repressive in so many different ways was in the air, and gay rights were a part of that,” Maher said.

The two men began recruiting others to join the Gay Liberation Front, putting classified advertisements in The Daily Northwestern. The group ended up including around 20 people, but a core group of six regularly attended meetings and organized events. They held meetings off campus at members’ apartments.

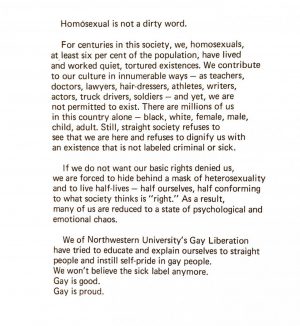

The Gay Liberation Front wanted be recognized as a campus organization, so they drafted a letter to faculty outlining their primary goals:

(1) “to educate the heterosexual community about homosexuality,”

(2) “to secure equal rights for all homosexual men and women,” and

(3) “to provide social and intellectual activities for the homosexual student.”

The letter ended with the Gay Liberation Front asking for faculty’s public support. They printed the letter and distributed it to all department heads.

“We weren’t just talking about making things better at Northwestern,” Ahmad said. “We’re talking about making things better in society at large and engaging the university to help take us there, which is certainly the kind of ambitious goals one can have when one’s a 20-year-old.”

Faculty support wasn’t unanimous — one department returned the envelope of undistributed letters, addressed to “Miss William Dry” — but the Gay Liberation Front’s request was approved, and they were officially recognized on campus.

Because there were no gay social events, Ahmad wanted to plan something special for the gay students on campus: a dance. They had recently asked the student government for funds and, to their surprise, were granted $670. With the money, the Gay Liberation Front rented the Patten Gym. A member of the group knew Corky Siegel, a musician in the Siegel-Schwall Band, and the band agreed to play.

“(The dance) was wonderful,” said Ahmad. “We printed up the leaflets, we set the date, and instead of it being just, 20 or 30 gay people that were brave enough to… go to a public dance, we packed the gym! It was just a lot of fun.”

“Music is a form of compassion,” said Corky Siegel, remembering the event. He was 27 at the time. “What it does for individuals and people and the world, and how it uplifts people… it’s just a form of compassion. More practically, a popular band that’s showing support adds a little more power to the people.”

Although the Gay Liberation Front originated as a gay advocacy group, the group also advocated for racial equality, boycotting gay bars with racist practices.

The Normandy was one of the largest gay bars in Chicago. Bars operated differently back then. Most were run by the mob and paid off police. Few had dancing licenses and were also very segregated. The Normandy often kept out black patrons by requesting multiple forms of identification.

The Gay Liberation Front compiled a list of demands. They wanted the bar to fix the air conditioning, obtain a dancing license and, most importantly, allow all patrons to enter regardless of their race.

They met with the owner of the bar and read off the demands.

“And he laughed at us, thinking what was this little scruffy group of college students going to do to his Normandy Bar that paid off the police, that got at least 600 or 800 (patrons a night),” said Ahmad.

But the Gay Liberation Front boycotted the bar that Friday. Ahmad said he believes they effectively killed the bar’s business that night.

“People would turn around the corner two blocks down from the subway station, see this ruckus in front of the bar… and they would, discretion being the better part of valor, turn heel and go right back to the subway and go someplace else,” said Ahmad.

The group boycotted again the next weekend, and the Normandy finally agreed to meet once more with the Gay Liberation Front once more.

The two parties met in a classroom in Kresge Hall. Ahmad remembers the bright, fluorescent lights shining down on the Gay Liberation Front as they faced off with representatives from the Normandy.

“This is an image that will forever be seared into my brain,” said Ahmad, remembering the night. “The visual was so great. It was like six scruffy gay boys and then two mafioso types in ties and suits stuffed between the return arm and the back of the chair negotiating with us.”

The owners of the Normandy agreed to all of the demands put forward by the Gay Liberation Front. And, after acquiring a dancing license, the bar became more popular than ever. Other bars soon followed suit and obtained dancing licenses as well.

The group has evolved and now exists as the Rainbow Alliance. Fifty years later, Ahmad’s support in the fight for equality is unchanged. He said he remembers the importance of protests when he was advocating for change.

“The notion of going out in numbers was profoundly important, but it’s profoundly important for every group,” said Ahmad. “I would hate to get stuck on a freeway in Los Angeles because a whole bunch of gay rights activists or (Black Lives Matter) activists sat down and closed it up, but if these people are willing to sit in the freeway, be arrested, go to jail, fight the arrest, pay the fine, get released and do it again, more power to them. Because sometimes you gotta shout to be heard.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @apchun01

Related stories:

— 50 Years of Queer Anger: While pivotal, Stonewall wasn’t the beginning