Defunding 101: What does it mean to “defund the police” and why is it gaining traction?

Daily file photo by Daniel Tian

EPD vehicles. On Monday, multiple claims against police chief Demitrous Cook and the city were dismissed.

June 18, 2020

In the wake of George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police, the Black Lives Matter movement and calls to address systemic racism and police brutality have taken center stage in nationwide protests.

Evanston Fight for Black Lives, the local youth- and female-led effort to support the Black Lives Matter movement, has called on the mayor and City Council to defund the Evanston Police Department.

The call to “defund the police” has been both an organizational slogan and a concrete demand, in which advocates have identified police as perpetrators of systemic racism and have been pushing for divestment from police spending. Defunding the police does not imply reforming the current system, but instead pushes for a comprehensive undoing and restructuring of public safety, starting with reducing the police budget.

At least 17 cities have already proposed or pledged to defund aspects of their police departments, including Minneapolis, which voted to disband the department as it stands, New York City and Los Angeles.

While some Chicago aldermen have proposed plans for defunding the police, the city has a substantial history of unsuccessful police reform, including two proposed oversight organizations, the Civilian Police Accountability Council and the Grassroots Alliance for Police Accountability, neither of which have yet to come to fruition.

Another historical roadblock to Chicago police reform is the city’s police union, which WBEZ called “the largest bargaining unit of city employees on the City Hall payroll.”

Ties to the prison abolition movement

Christopher Harris, a postdoctoral fellow in Northwestern’s African American studies department, described the call to defund as an “abolitionist demand.”

“It pinpoints one part of an abolitionist goal, which is the redirection of resources away from the carceral state, away from punishment, away from force, toward more community-centered initiatives that we know keep people safe,” Harris said, referencing healthcare, housing, education and mental health services.

The aim is to abolish prisons and the prison-industrial complex, or “the political economy of interest and money that prop up the prison system,” Harris said. A piece of this theory draws the line from slavery to mass incarceration via the disproportionate policing and incarcerating of black and brown communities.

Evanston Township High School alum and self-identified abolitionist Adam Marquardt explained the abolitionist framework.

“Abolition is about believing that punishment itself is antithetical to justice,” Marquardt said. “Communities are valuable. Instead of throwing someone away in prison to let them rot, we should be asking ourselves, ‘How has society failed this person?’”

What does “defund” actually mean?

As the word suggests, the call to defund means taking money away from the police budget. A crucial part of defunding involves the reallocation of funds to other sectors.

In particular, advocates of defunding are often proponents of using the money to invest in recreation and community centers, fund multicultural programming, close the K-12 achievement gap and fund social service workers, among other initiatives.

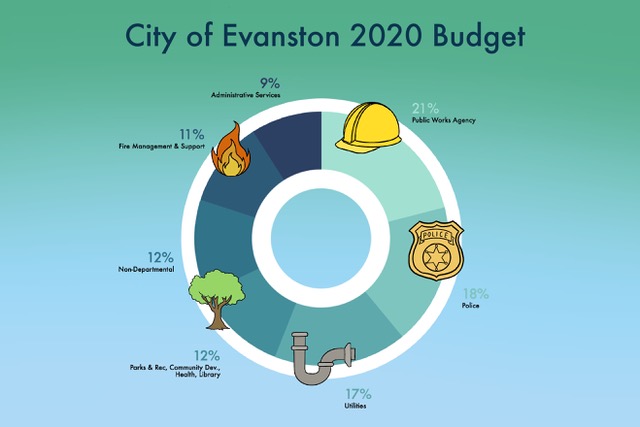

Evanston Fight for Black Lives has recommended funds from EPD be allocated to sectors like parks and recreation, community development and health.

According to philosophy Prof. Jennifer Lackey, director of the Northwestern Prison Education Program, first-line intervention that requires specialized community care currently falls under the jurisdiction of the police.

And in 2020, Evanston allocated 17.6 percent of its budget to the police, more than the total amount allocated to Parks and Recreation, community development, health and library combined.

Lackey said this overuse of police leads to the criminalization of activity related to mental health crises and drug- and alcohol-related issues. Defunding would involve delegating intervention to specialists. In other words, when someone is having a mental health crisis, a social worker or mental health professional could be the first on the scene, instead of an armed police officer.

“Not nearly as radical as it might sound”

According to Lackey, the racial equity crisis of mass incarceration is directly linked to policing.

“Once you take that first step into the criminal justice system, it’s very difficult to extract yourself, especially if you’re a poor, black person in America,” Lackey said. “So a structural remedy for much of the mass incarceration that we find is stopping those initial arrests.”

Residents that identify as black or Hispanic make up 70.4 percent of the Illinois prison population, but make up 31.2 percent of the overall Illinois population, according to the Illinois State Commission on Criminal Justice and Sentencing Reform. In Evanston, black people comprise 62 percent of arrests but only 18 percent of the population.

Lackey added that this disparity emphasizes the urgency in reimagining the public safety system and suggests that it may be “not nearly as radical as it might sound.”

“Black and brown communities are overpoliced,” Lackey said. “(Suburban, affluent) communities are not using most of their money to pay for police. They’re using it to invest in communities and programs and support…It’s hard to see someone who would want to push back against that.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @BinahSchatsky

Related Stories:

– Students call on University to divest from police forces and invest in Black communities

– Local academics, Evanston officials discuss race and policing in virtual roundtable