‘A dark cloud’: Evanston leaders concerned with disproportionate rates of coronavirus among black and Latino residents

May 22, 2020

For weeks, preliminary data showed black Americans in Illinois, among other states, were disproportionately contracting and dying from COVID-19. Not only has that trend continued in cities like Evanston, but Illinois Department of Public Health statistics show a steady increase in cases among Latino city residents as well.

Black residents comprise 24.6 percent of confirmed cases, yet make up 16.6 percent of the city’s population, according to Census data. Latino residents make up 18.3 percent of positive cases but represent 11.8 percent of the population. However, white residents make up just 28.5 percent of cases, despite encompassing 59.4 percent of Evanston’s population. (Another 15.98 percent of cases were “left blank” and considered their own category by the IDPH.)

The state passed more than 102,000 confirmed cases and Evanston reached nearly 615 cases as of Thursday afternoon. Many community leaders are concerned about COVID-19’s impact on black and Latino residents — and about the city’s response.

Misinformation, medical distrust among reasons for high rates

The state’s shelter-in-place order went into effect March 21. But those deemed essential workers continue to head to their jobs at places like hospitals and grocery stores, where they interact with up to hundreds of people a day. Black Americans and Latinos are more likely to hold these positions. often forced to work while at risk because of economic circumstances.

Michael Nabors, senior pastor at Second Baptist Church, said misinformation or outdated recommendations have prevented black and Latino residents from getting tested or going to the doctor. He said conflicting news about matters like testing availability from the federal, state and city governments has been frustrating to see.

“It creates a sort of dark cloud,” Nabors said. “Instead of there being a message of clarity to the American people (like), ‘This is what you need to do. Here are three steps you need to take,’ it’s clouded in this messiness that is a part of this administration and how it’s handling the pandemic. That boils down to what’s happening in Evanston.”

Ald. Cicely Fleming (9th) said many people do not see the city government as the most trusted source of information — and getting those levels of trust back up may be “one of the hardest things.”

“They have to know who their council representative is. They have to be able to access that person to feel like they’re getting an as prompt as possible response from someone,” Fleming said. “You have to trust that the person understands your life experience somewhat.”

Fleming added that information is more difficult to disseminate because most government entities are still learning, never having been under strict limitations before. She said leaders are not trying to mislead, but information changes almost daily. It’s a balance between giving people as many details as possible without causing more anxiety, she said.

Disproportionate rates in Latino, black communities

Despite city efforts, the number of cases among Evanston’s Latino residents continues to rise. Increased testing efforts and rates can partly explain the trend, but societal factors also play a large role. Multigenerational households, high numbers of essential workers who commute to work, immigration status and more contribute to disproportionate rates, said Rebeca Mendoza, a regional grants officer for a nonprofit.

(Note: The IDPH lists Hispanic as a separate race rather than an ethnicity, a categorization that differs from Census notation and doesn’t always match doctors’ forms or individual self-perception.)

Data was compiled using internet archives of the IDPH website when available. Multiple FOIA requests for a full set of data were denied.

Rebeca Mendoza said when the crisis first began, misinformation that Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers could potentially come to peoples’ homes circulated, frightening those in undocumented or mixed-status households. Rebeca Mendoza said she saw a need for a trusted source of communication, so she started to frequently post information in both English and Spanish in the “Hechos en Evanston (Evanston Latinos)” Facebook group, which she moderates.

“I really felt that there is a huge gap, and letting people know what was going on… was so important, especially early on, when people were freaking out,” Rebeca Mendoza said. “People need to have things in a way that they can understand it, whether it’s in their language, or in an audiovisual format, and coming from somebody they can relate to or they know.”

Community organizer Stephanie Mendoza said many Latinos in Evanston, especially undocumented individuals, face a technology barrier and are therefore not a part of the city’s social media networks or newsletter mailing lists.

She added that though Fleming has been reaching out, she hasn’t seen those efforts from most city officials. Fleming said she regularly updates her Facebook page with demographics and other information related to the coronavirus.

“I know that the bilingual staff in the city are really trying to send out information in Spanish,” Stephanie Mendoza said. “I get information all the time to post in our closed Facebook group and other… pages that have a lot of Latinos — and then again, not everyone is on social media. I’ve had to rely a lot on text messaging, including texting family and friends and asking them to text… other people that I know in the community and so on.”

While the city has translated “almost everything” into Spanish, Fleming said the city still does not have a specific translation policy. She added the materials that have been translated into Spanish, like the bilingual website or newsletters, have actually been opened at very low rates. Fleming said she has asked the interim city manager, Erika Storlie, to send more text messages about COVID-19 in Spanish.

Stephanie Mendoza said Evanston needs to use available tools to make better attempts to reach out to communities of color. Text messages in Spanish could answer common questions, she said, providing basic information about the virus, testing locations, when to wear face masks and more.

“I personally have been part of some online chats or Zoom meetings, and the community’s asking questions like, ‘If I live with other people, how do I self-isolate? (If) there’s more than one person in my house, if there’s not more than one bathroom,’” Stephanie Mendoza said. “Our health department has to do a better job at providing guidance — simplified, direct guidance — to this community.”

Ramped up city efforts still fall short

A notable part of the city’s coronavirus plan involves Mayor Steve Hagerty’s consistent COVID-19 Task Force meetings, which began March 17. Task Force members include local and state officials, as well as representatives of various community factions. According to public agendas, racial disparities have been explicitly mentioned twice out of 20 reunions, including May 1 meeting’s Spotlight portion.

Nabors, Evanston public health manager Greg Olsen and Pamela Mitchell-Boyd, system director of diversity and inclusion for AMITA Health, presented reasons why communities of color were facing high rates, including suspicion of healthcare industries, lack of adequate health insurance and negative medical interactions. In addition, they reported that almost 40 percent of jobs held by people of color were vulnerable to furloughs, hour reductions or layoffs.

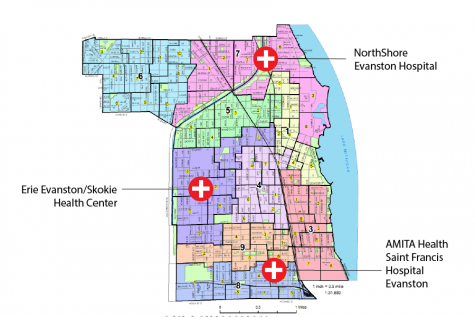

Another concern was the lack of accessible testing. Earlier this month, Erie Evanston/Skokie Health Center, located at 1285 Hartrey Ave., became the city’s third testing site. Despite its critical location in the 2nd Ward and near the 5th Ward, where more black and Latino residents are concentrated, the clinic currently only accepts established patients.

Stephanie Mendoza said the city needs to make testing more accessible, particularly for uninsured and undocumented populations.

“A lot of our older mothers who are caregivers and who are also essential workers, they don’t have transportation,” Stephanie Mendoza said. “They don’t drive. So we’re telling them, not only are you sick, but hop on a bus (to get tested), potentially get other people sick?”

Ike Ogbo, the city’s health and human services director, said the discussion about race gave a bigger picture of the spread of the virus within Evanston’s minority groups, especially those without insurance or test access. However, the only solution listed in the May 1 agenda was potentially providing “mobile” testing for shelters and people experiencing homelessness.

Ogbo said the city intends to implement that option, and he is currently in conversations with a hospital to finalize site expansion.

Several community leaders and city council members said they are still concerned about the lack of demographic data on Evanston’s coronavirus tracking website. While there is a link to an IDPH page where people can search their own zip code and pull up specific information, Evanston’s site only lists the number of cases and deaths. Nabors, who is also president of the city’s NAACP chapter, said breaking down the percentages could help minority communities.

“That’s critical and important,” Nabors said. “We don’t know specifically who’s getting it — all we have is broad brushstrokes of messaging for everybody in the community, and that doesn’t seem to be working.”

In mid-April, when Evanston was still approaching 200 cases, Olsen told The Daily racial data could not be released on the city website because of privacy concerns. Now, he said there have been internal discussions about what data available on the state’s website could be shared in the future.

“We don’t want to be viewed as, ‘Why isn’t Evanston sharing this data?’ We want to be as transparent as we can,” Olsen said. “There’s enough unknown about this virus that we don’t want to contribute to any more of that unknown.”

Olsen and Ogbo did not state a specific timeline for when demographic information might be published on the city’s website.

Throughout the past months, Nabors said a strong sense of community has remained important for black residents. Along with soup kitchens open on Mondays and Tuesdays, he said the Second Baptist’s regular Sunday worship services reach up to 2,000 people online.

However, he said it’s important to focus on getting resources for black and Latino residents who have been affected the most in terms of health and finances. Stephanie Mendoza echoed this sentiment, adding that people of color need more city support, especially the most vulnerable members — for example, those who have contracted the virus but still have to commute to work.

“How do we, as a community, tell people, ‘You don’t have a support system, but I want you to support your community and stay home,’” Stephanie Mendoza said. “These are people that interact with so many people every day. They are our essential workers. If (the city doesn’t) do something to support them, it’s going to be very, very hard to contain this virus.”

Ella Brockway contributed data analysis.

Email: mmartinez@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @mar1ssamart1nez

Related stories:

— Undocumented Evanston residents face financial, medical struggles without government aid