From ball fields to the medical field: Former Northwestern athletes fight on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic

May 4, 2020

As a lacrosse player at Northwestern, Kate Darmody Burke was part of a major breakthrough.

Darmody Burke (Weinberg ‘05) was in coach Kelly Amonte Hiller’s first recruiting class after the program regained varsity status before the 2002 season. That class graduated as national champions with an undefeated senior season in 2005, finishing with a perfect 21-0 record.

The Wildcats, just four years after restarting their program, had begun a dynasty — this was the first of five straight NCAA titles and seven in eight years.

“I have an incredible bond with that group of ladies that lasts until today,” Darmody Burke said. “I’ve been very blessed, really taught the value of working together to achieve a common goal, and having a whole heck of a lot of fun while doing it.”

But now, Darmody Burke is working toward another important breakthrough. A nurse managing an intensive care unit at Advocate Trinity Hospital in Chicago’s Calumet Heights neighborhood, she works 12-hour shifts most days, making sure the nurses in her unit have the resources they need to help COVID-19 patients.

While the work is exhausting, Darmody Burke said the lessons she learned as a student-athlete are still guiding her in her current role. Amonte Hiller had her team do an exercise called “appreciations,” where players told each other something very specific they appreciated about them, and Darmody Burke said she uses that exercise to help with team building.

“It’s really important to rely on the help of others,” Darmody Burke said. “You can’t win a championship with just one person. Relying on those relationships and utilizing those strengths has really helped how I manage my own units right now.”

“Competitive personalities”

Hospitals all over the United States are struggling to keep up with the severity of the coronavirus pandemic, and medical professionals everywhere are feeling the stress. Darmody Burke said working in an ICU attracts “competitive personalities,” so a lot of former college athletes end up there — including several from Northwestern.

Kerin Jones (Weinberg ‘85) played both field hockey and lacrosse at NU. She won Big Ten titles in field hockey in 1983 and 1984 and made two NCAA Tournament appearances in lacrosse. She is now a Continuing Medical Education director at Detroit Receiving Hospital and an associate professor of medicine at Wayne State University.

Jones said almost every patient she’s seeing has the coronavirus.

“For us to go see these people, it takes a lot of effort,” she said. “Putting on and off the equipment, trying not to contaminate yourself. You don’t see as many people, but it’s mentally and emotionally exhausting.”

Jones is used to taking care of sick people, but the challenge now is doing so while trying to avoid getting sick herself. She said the discipline and time management she learned as a student-athlete is helping her prepare to see each of her patients, and working with her colleagues at the hospital is similar to working with her teammates.

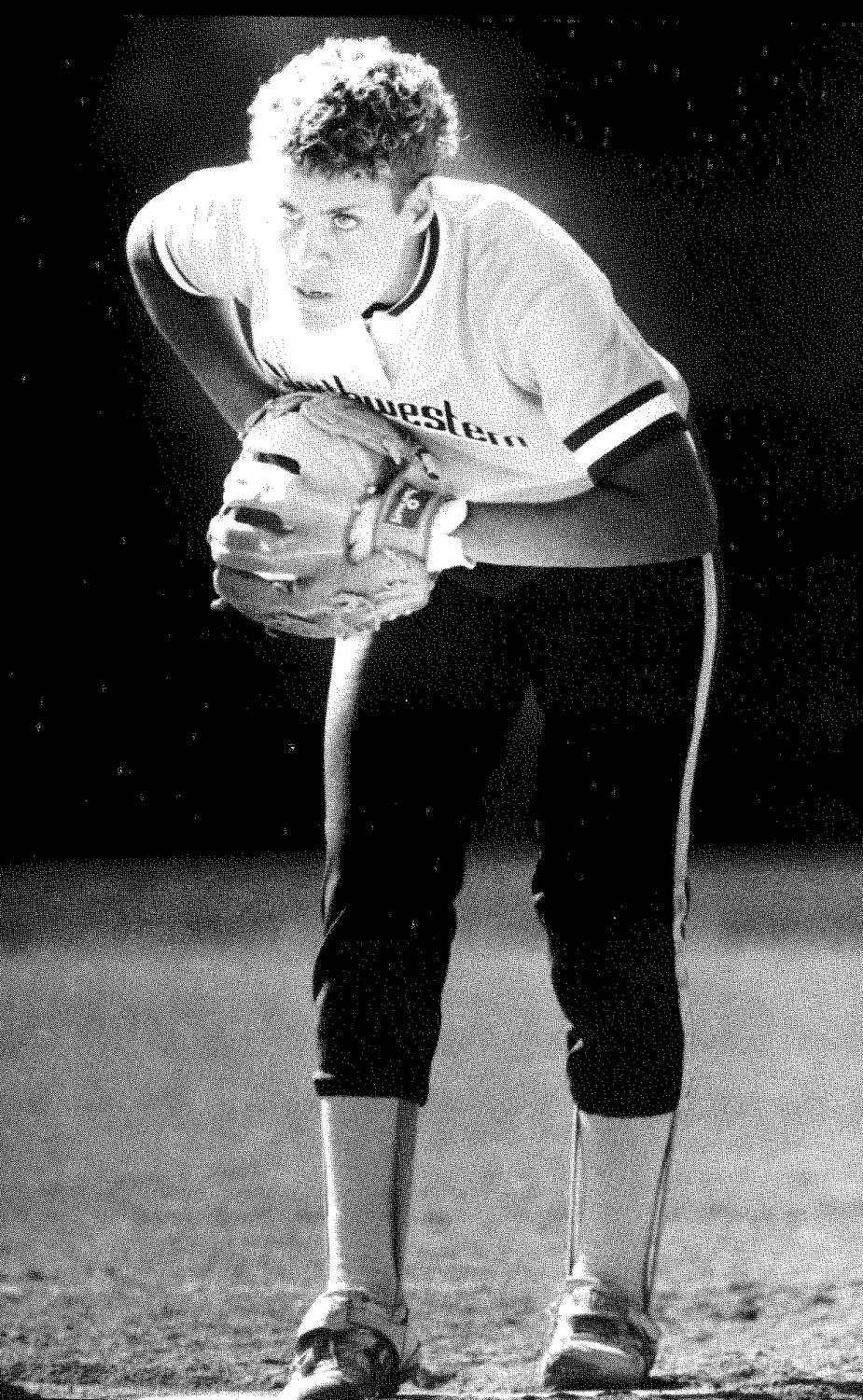

Chinazo Opia Cunningham (Weinberg ‘90) is a Northwestern softball Hall of Famer with a career 1.19 ERA, including an incredible 0.38 mark for the 1987 conference champions that earned her Big Ten Rookie of the Year honors.

Cunningham has practiced internal medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx borough of New York for 22 years and is also a professor at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. She said the lessons she learned from legendary coach Sharon Drysdale stick with her today.

“Her depth of understanding, how to get the most out of people and how to be strategic to win was really cutting-edge,” Cunningham said. “I’m a researcher and I apply for grants all the time, and it’s a very competitive process. It’s sort of like a game — being strategic in terms of how I present my projects and apply for grants, all of those things have similar aspects to sports.”

Chinazo Opia Cunningham pitched for Northwestern from 1987 to 1990. Cunningham is now seeing COVID-19 patients in the Bronx borough of New York.

Direct experience

Kristine Cieslak and Ryan Padgett’s experiences with COVID-19 were not limited to seeing infected patients — they contracted the disease themselves.

Cieslak (Weinberg ‘89) won two Big Ten titles in softball as a left fielder and played in the 1986 Women’s College World Series. She made the all-conference first team as a senior. Now, Cieslak is an attending physician in the pediatric emergency department at Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago.

With limited access to testing, she had no choice but to assume everyone she was treating with COVID-19 symptoms was positive, even though children are less vulnerable to the disease than older populations.

Both Cieslak and her husband had the virus, with her husband spending 10 days in the ICU. She said she has “changed forever” from her experience with COVID-19, realizing there are certain things in life she can’t control.

“I had a fever for 12 days, extreme fatigue,” Cieslak said. “I’m still an athlete, I’ve got a lot of energy, (but) I could barely get out of bed in the morning, and it would take me hours to just get enough strength to go put together a piece of toast for myself. You sort of have to surrender to the virus and realize you don’t have control of it. It is going to take you on its own journey.”

Padgett (Weinberg ‘96) had an even more chilling experience. An offensive lineman, Padgett was a senior on the historic 1995 football team that won the Cats’ first Big Ten title since 1936 and went to the Rose Bowl.

He is currently an emergency physician at Evergreen Health Medical Center in the Seattle suburb of Kirkland, Washington — the site of the first major COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S. He was unknowingly treating coronavirus patients before the first confirmed death, then came down with the disease himself on March 7.

The virus came as a shock for Padgett, who, by his estimate, had taken five sick days in 21 years working in medicine. A colleague convinced his fiancé to buy him an oxygen monitor, and his readings grew progressively worse, so she brought him to the hospital on March 11, where he was placed in a medically-induced coma.

He didn’t wake up for more than two weeks, eventually coming to at a different hospital. Padgett didn’t initially know how much time had passed or how severe the pandemic had become.

Despite his experience, Padgett said seeing the support of his fellow doctors and nurses was heartwarming and gave him a sense of hope that his generation can work to defeat the virus.

“You wake up and get your cognition back and they start to tell you the story of what happened,” Padgett said. “I couldn’t see my family for a month. This was as tough as you can get. You’ve survived this brush with death, and the ones you love the most are involved in making these gut-wrenching decisions.”

Ryan Padgett was an offensive lineman for Northwestern who played on the revered 1995 Rose Bowl team. He is now a physician in the Seattle area, where he survived a frightening experience with COVID-19.

The biggest game of their lives

Darmody Burke and Padgett’s teams both went through some rough seasons when they were underclassmen before making historic breakthroughs as seniors. Darmody Burke said that taught her the importance of patience and continuing to work hard even in the toughest of times — a lesson she’s carried with her during the pandemic.

“Sometimes you just have to focus on the process and the product takes care of itself,” Darmody Burke said. “That was a principle we learned from (Amonte Hiller). You’re not going to be the best in a day, you’re not going to be the best in a month, but if you keep doing your best every single day, you’ll get there.”

Cieslak also said she learned about the importance of the process playing at NU, which is helping her keep a rational perspective on the chaos COVID-19 has caused. Being a student-athlete also taught her focus and efficiency.

She said the same adrenaline she felt on the softball field appears when working with patients and her medical team, and that saving a patient is her new kind of victory. Being an athlete and a leader on the field has helped her succeed as a leader in the hospital.

“It’s the positivity that Northwestern student-athletes have, because they’re unique,” Cieslak said. “You’re stretched in ways you never knew you would be, and from that comes tremendous strength. When those tough times come up, you realize you’ve got it inside you. I’ve used it a lot of times in my life when I need to overcome something, and it never failed me.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @bxrosenberg

Related stories:

— Northwestern doctors upend family life to fight at front lines, NM builds capacity for peak

— With no playbook and a finite supply, Evanston health workers must gear up for the long haul

— Evanston hospitals conduct thousands of COVID-19 tests, expand to antibody testing