Northwestern launches prison education program, will provide college credits to inmates

October 5, 2018

CREST HILL — For 37-year-old inmate Tony Triplett, life often felt “colorless.”

He is serving a life sentence in Stateville Correctional Center after being convicted of raping and killing two women in 2006. Triplett, who claimed innocence, said he struggles to remember he is more than just a prisoner with an assigned number.

On July 30, Triplett walked into an interview with officials from Northwestern University and the Illinois Department of Corrections with a new sense of hope in the air. Clutching a purple NU folder, which he said made him feel more like a student, Triplett answered questions about literature and systematic oppression for 15 minutes.

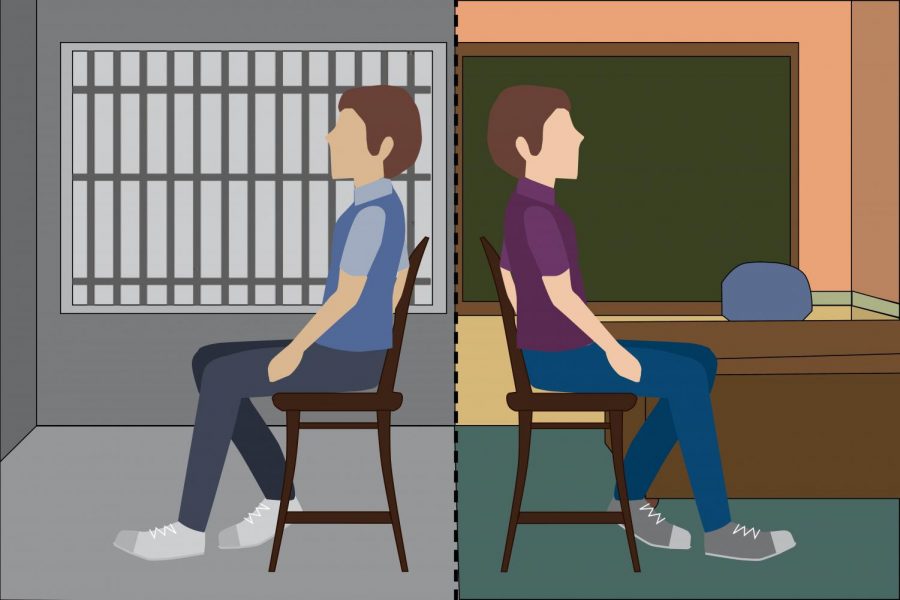

Now, he is one of 22 Stateville inmates in the Northwestern Prison Education Program, an initiative launched this fall. The program, spearheaded by philosophy Prof. Jennifer Lackey — who has independently taught classes at the prison in the past — allows inmates to learn and receive credits through the School of Professional Studies.

“I want to be able to show my children that this is what I’m doing in prison here. I’m not just rotting here,” Triplett said.

Lessons on law and sociology

Lackey said the ultimate goal of the program is for the inmates to feel like they’re part of a community — one that supports each other in and out of the classroom.

Participants will take different classes taught by Northwestern professors each quarter: in the fall, a class on inequality, poverty and race with sociology Prof. Mary Pattillo and a class on policy aimed at reducing systematic violence with School of Law Prof. Sheila Bedi; in the winter, a class on literature and film about the U.S.-Mexico border with English Prof. John Alba Cutler; and in the spring, a class on decision-making and human cognition with psychology Prof. David Smith.

Pattillo said her first experience as a prison educator was as a guest lecturer for one of Lackey’s previous non-credit classes at Stateville, which is a little over an hour away from Evanston. She said seeing how the inmates were “hungry for conversation” inspired her to sign on as a professor for the new full-fledged program.

Her class, which is also being offered as a separate freshman seminar on the Evanston campus, is intended to help students think about Chicago from a different perspective — especially since many of the inmates have an outdated memory of the city due to their long incarceration.

“My learning goal is really that students make the familiar strange,” she said. “Make what they think they know –– they see a city, they see housing, they see public housing, they see crime, they see cultural festivals –– and complicating that beyond what they see.”

Pattillo said she foresees some difficulties in teaching because of the inmates’ lack of internet access, but hopes to keep them connected to the outside world through supplemental readings.

Bedi’s class, which is composed of 10 inmates and 12 students in the Pritzker School of Law, will have the participants closely analyze the justice system. She said she chose this topic because it hits close to home for many of the Stateville students: They have all been through the system, and many have experienced violence.

The first two sessions held so far have been dynamic, Bedi said. Following a series of ice breakers –– which Bedi said students roll their eyes at, even in a prison classroom –– there were many in-depth conversations around race and justice, the continued repercussions of slavery and more.

Interactions between students in Evanston and Stateville inmates are important in both classes. Pattillo said she might have students swap assignments or have the Evanston freshmen visit the prison. In Bedi’s class, the law students will commute to Stateville weekly to brainstorm policies that tackle systematic violence.

Seventh-year graduate student Anya Degenshein, an advisory member of the program, said she hopes these interactions will make more undergraduate and graduate students who aren’t studying criminal justice think about the relationship between inequality and incarceration.

The presence of law students in her class has also been inspiring to the inmates, Bedi said.

“I’m quoting one of our students who said … (NU students) gave him hope that the justice system might ultimately transform into a system that recognizes the humanity of everyone, regardless of race,” Bedi said.

The duty of higher education

Provost Jonathan Holloway told The Daily he approved the program because it was the “right thing to do.”

“Universities should be places that make the world better, heal the world basically,” he said. “So this kind of initiative –– prison education –– seems to be of a piece of that larger philosophy of what a university is there to do.”

NU isn’t the first school to offer this kind of program. Community colleges have been hosting prison education classes since at least 1982. Cornell University began granting college credits to New York inmates in 1999 and provided its first set of associate degrees to inmates in 2012. The Ivy League school now also issues a Certificate in the Liberal Arts to those who have taken six courses across the discipline by Cornell faculty.

And the benefits of prison education are well documented. Inmates who have taken classes in prison are 13 percent less likely to be re-incarcerated than peers who have not, according to a 2013 study by the RAND Corporation, a global policy think tank. The study, funded by the Justice and Education Departments, also found that prison education is actually cost effective: The government spent $5 less on corrections for every dollar spent on correctional education.

Rob Scott, the executive director of the Cornell Prison Education Program, said graduation for inmates who received an associate degree was an “emotional” and “uplifting” experience because it was the one day the prison gave inmates the space to be celebrated.

Offering prison education also positively affects others beyond just those accepted into the program.

Corzell Cole, who had taken classes with Lackey prior to being accepted to NU’s prison education program, said his pursuit for a degree has caused younger inmates to look up to him.

“These young guys, most of them are looking for a big brother. They see me get my GED, they see me going to school, they see me read,” he said.

The battle for an NU degree

Although Stateville students currently receive college credits, Lackey said she hopes Northwestern will one day provide the inmates with degrees, similar to Cornell’s program.

Holloway, however, said it is too early to discuss possibilities beyond providing credits. He added that offering degrees to inmates can be difficult because the University does not have as much control over the prison’s learning environment as it does over the Evanston campus.

“Interacting across institutional space –– whether it’s another university, a community college or a prison system –– there is all kinds of issues of quality control that we don’t know about,” he said.

Scott said it can be difficult to ensure that the inmates’ skills are comparable to those of traditional students with university degrees because the former group faces issues like limited internet access, which hinders research opportunities.

Still, Lackey said preserving the academic integrity of courses will be the program’s top priority. She added that in addition to it being a major personal accomplishment, an NU degree could help “offset” the many disadvantages inmates face when they are released from prison: Only 45 percent of ex-inmates remained employed after eight months in 2008, according to a study by the Urban Institute, a social policy think tank.

For Triplett, however, education is more than just another line on his resume.

“They’re giving us the chance to set the narrative of what prison is like,” Triplett said. “(In this program) we’re not inmates. We’re students, and (Lackey’s) a professor.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @ck_525