When your house is not a home: domestic violence in Chicago amid a pandemic

July 7, 2020

The Daily has chosen to rename sources who wish to remain anonymous for personal safety reasons. These sources are introduced with an asterisk.

Candace* was in the middle of taking her remote nursing final when her husband and his friend stormed into her Chicago apartment. Though the couple had chosen to separate two months ago, her husband refused to relinquish his key.

“They took my computer,” she said. “They took my television. They took my printer. They took everything, and we’re in a pandemic.”

With families in lockdown, family court processes postponed and other resources for domestic abuse less accessible, the pandemic has exacerbated cases of intimate partner violence, triggering an additional public health crisis. Victims of abuse, like Candace, have found themselves more vulnerable to repeat offenses from their abusers with less access to the legal protections they require.

Someone of any gender identity can be a victim or survivor of domestic violence. According to The National Domestic Violence Hotline, however, females from 18 to 24 and from 25 to 34 generally experience the highest rates of intimate partner violence.

As a mother of three children, Candace shared the laptop with her teenage son, who needed the device for remote high school classes during the academic year. These incidents are exactly what Candace feared in previous attempts to go through with divorce.

Last year, Candace realized that she had to make a choice between her life and staying with her husband. In the end, she made the decision to file for divorce. Candace’s final court date was scheduled for the end of March, but when COVID-19 brought the world to a halt, her court hearing was canceled too.

“All I did was make the decision that I deserve better,” Candace said. “And ever since I made that decision, I’ve been losing.”

Family law litigation is largely on pause because of the pandemic, said Margaret Duval, the executive director of domestic violence legal clinic Ascend Justice.

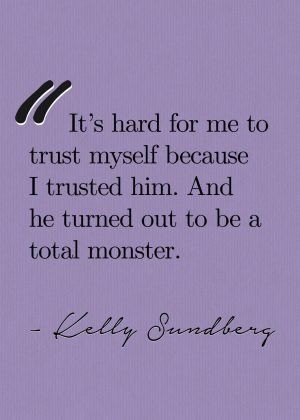

Seeking Orders of Protection

Victims or survivors are still able to obtain Orders of Protection by visiting the lobby of the Cook County Domestic Violence Courthouse. In person-visits are discouraged due to COVID-19, but are sometimes the only option for those who cannot receive legal support through any other means. While there is another option to obtain a protective order remotely, remote hearings can make managing the volume of protective order requests difficult.

In-person hearings are designed so that an attorney or legal advocate does not need to be present, Duval said. Remote hearings, however, require that an attorney or advocate accompany petitioners. The change increases the demand for staff, reducing the number of protective orders processed.

Prior to the pandemic, 50 to 80 people cycled through the courthouse each day to petition for Orders of Protection. Now, Duval said the courthouse cannot realistically staff even 50 remote hearings in one day.

But filing a protective order is only the beginning.

The courthouse has also postponed subsequent court hearings for ongoing cases amid the pandemic, which has led to a backlog, according to Melanie MacBride, the managing attorney for the Safety & Family Practice Group of Metropolitan Family Services in Chicago.

In an attempt to address the backlog, remote court dates will be held for ongoing cases that can be resolved and disposed of beginning July 6, MacBride said. These include cases with scheduled hearings from July 6 through August 3, where the petitioner and respondent are able to reach an agreement on a long-term order or the petitioner decides not to go forward with the case.

Cases that cannot be neatly resolved, where the respondent is not cooperative and the petitioner wants to continue with the protective order, will tentatively be heard in September depending on the state of the pandemic, said MacBride.

Candace filed a request for a protective order against her abuser, only to be denied it because the abuse directed toward her did not classify as “physical.” She said the added barrier of having to meet certain criteria to obtain legal protection was infuriating.

“Do you want me to lie that he is beating me or do you want me to tell the truth?” Candace said. “He is torturing me. Do you want me to commit suicide? Will somebody hear me then? Mental abuse is the same as physical abuse, but who cares about us?”

While Candace is not living with her abuser, many others seeking protective orders during COVID-19 are. Early shelter-in-place protocols compounded the difficulty of reaching legal assistance organizations for those quarantined with their abuser. As restrictions are lifting, victims or survivors may be more comfortable making that call, said Renata Stiehl, the supervisor of Metropolitan Family Services’ Court Advocacy Program.

A victim or survivor with a protective order can petition for exclusive possession of the residence and request that the respondent is ordered to leave. But during a pandemic, the question emerges: Where can the respondents go?

Stiehl said the pandemic put judges in a tough position. Typically, the respondent has friends, family and the means and resources to live elsewhere. But with COVID-19, many of those options may no longer be available to those who wish to remain cautious.

“From a public interest perspective, no judge wants to make somebody homeless,” Stiehl said.

More than just a piece of paper

Judicial decisions also must consider how a situation can escalate. Stiehl said predicting escalation is even more challenging amid a pandemic, where couples may be influenced differently by the associated stressors.

“There’s always been an abuser who could hold their victim hostage. We’ve seen those cases,” Stiehl said. “Now, that abuser is also constrained, restricted and forced to stay within his home. It’s a recipe for all of those tensions to escalate faster than they normally might.”

Safety planning holds greater importance to victims or survivors than before because, even with an order in place, “at the end of the day, an Order of Protection is a piece of paper,” Stiehl said.

Stiehl suggested victims or survivors develop a signaling system with their neighbor, identify a safe word to communicate with their children and find excuses to leave their home or to encourage their abuser to leave their home, even for a short period of time.

However, previous options of temporarily living with a friend or a parent as a means of safety planning may also no longer be viable options due to concerns over the spread of the virus, especially when vulnerable populations are involved. Fewer people may send their children to their grandparents’ homes, for example, to avoid infecting older members of the household.

If the victim or survivor is working with an advocate, Stiehl said the advocate can increase regular check-ins as a form of safety planning. That way, if the victim or survivor is unresponsive, advocates can reach out to their emergency contact to ascertain whether the lapse in contact is harmless or indicative of danger.

Advocates will also be contacting victims or survivors to discuss new changes that were implemented on July 6.

“I have no one here and I have no support”

Individuals who entered COVID-19 without an advocate can still be connected through services like a consolidated hotline run by Sarah’s Inn, Family Rescue and Metropolitan Family Services. Advocates on the hotline collectively fielded over 740 calls during the months of April, May and June, Stiehl said.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Stiehl said advocates had to tackle the challenge of spreading information on existing remote resources, as the norm used to involve walking directly into the Cook County Domestic Violence Courthouse, Stiehl said.

Many immigrants and refugees in abusive situations felt the pain of isolation before the pandemic. Those who are confronted with language barriers may also be separated from strong communal support, all the while unable to understand and communicate effectively in English.

Neha Gill, the executive director of Apna Ghar, said it’s a challenge to make sure new information about COVID-19 and other external resources remain accessible across different languages. Nonetheless, communication to clients has improved substantially since April.

Apna Ghar, a Cook County nonprofit that provides gender-based violence services, works primarily with immigrants and refugees, and Gill said the group collectively speaks 20 different languages out of their commitment to cultural competency.

Even with strong support networks in place, victims or survivors may avoid seeking help due to xenophobia. United States-born citizens often believe that gender inequality is greater in different cultural communities. In order to combat these stereotypes and weaken a presumed presence of misogyny, fellow community members may advise victims or survivors to not say anything or to “let us try to figure it out”.

Gill said patriarchy is the cause of gender-based violence, not any particular culture. But members of marginalized communities continue to face the decision between seeking help and perpetuating a harmful stereotype or remaining silent and enduring abuse.

Anna*, a South American immigrant, did not get to make this decision herself. Over six months ago, she was hospitalized. While her ex-husband had been verbally abusive to her before, the incident was the first time she was physically assaulted.

“I have no one here and I have no support,” she said.

Aside from talking on the phone with her mother in South America, Anna suffered her abuse in isolation.

During her stay in the emergency room, her counselor warned her that this was “just the beginning” and that he would be physically violent toward her again. Anna was connected with Apna Ghar, began the divorce process and requested a protective order.

Anna continues to receive support and therapy through Apna Ghar remotely. To cope with her anxiety surrounding COVID-19, her therapist has instructed her with some physical exercises, which Anna said have been improving her mood.

Anna can freely communicate with Apna Ghar over the phone because she rented a residence away from her abuser. Many victims or survivors, however, do not have the resources or the opportunity to physically move away from their abusers.

Gill said initially, Apna Ghar had seen a decrease in incoming calls and an increase in the number of emails and texts they received, indicating that the pandemic possibly made calling more difficult for people. Now, the numbers of calls are increasing as Illinois is opening up.

Finding a safe space

Victims or survivors who find the opportunity to make a call, whether that be to a hotline or Chicago-based organization such as Apna Ghar, can obtain alternative housing from a city shelter.

Connections for Abused Women and their Children, a Cook County nonprofit that advocates for abused victims of domestic violence and their children, started Chicago’s first emergency domestic violence shelter.

The shelter provides comprehensive individual and group counseling for victims or survivors to decide “the next step on their journey to living a life free from violence,” CAWC’s executive director Stephanie Love-Patterson said.

Before the pandemic, the shelter could house up to 42 women and children. They’ve now reduced the number of available beds to 27 to comply with social distancing regulations.

Since some victims or survivors began the process of securing safe, alternative housing before COVID-19, they’ve been able to leave the shelter to make room for other families. If the shelter reached full capacity, Patterson said placing that family into a hotel or Airbnb were viable options with government funding. With that funding, CAWC also provided PPE for residents. As of June 30, the Illinois Department of Human Services ended that program and CAWC cannot house more than 27 individuals, Patterson said.

The use of external housing had been essential in maintaining safety measures within the shelter. When a resident in the shelter came down with a fever, CAWC temporarily moved the resident to a hotel to self-quarantine.

Patterson emphasized that initially, the increase in shelter requests was not as large as may have been expected because it was challenging for victims or survivors to find the space to call. But as Illinois is loosening restrictions, victims or survivors have had a greater freedom to contact shelters and the number of shelter requests are on the rise.

Though protective orders and advocates’ work can provide physical safety, victims or survivors continue to struggle with emotional wounds, even after they’ve left their abuser.

“I began to believe what he said about me,” Candace said. “‘I’ll never be anything without him. I’m a horrible person.’ All I saw was his words in my mind. And what he deposited in me, I found myself depositing in my children. We’re all just walking around the house bleeding.”

“I began to believe what he said about me,” Candace said. “‘I’ll never be anything without him. I’m a horrible person.’ All I saw was his words in my mind. And what he deposited in me, I found myself depositing in my children. We’re all just walking around the house bleeding.”

Candace has recently come to the conclusion that she is a victim of domestic violence, which has not been easy.

“That’s still something that I’m struggling with because I’m strong,” Candace said. “I did this for my marriage. I always thought that I could save him, but in the midst of saving him, I lost myself.”

She said she realized finding a therapist meant investing in herself. Candace scoured the internet for therapists in her neighborhood, and began to see someone regularly.

In the black community, therapy may be associated with, “You’re crazy, something’s wrong with you. Go to church, pray about it,” Candace said.

But she knew she needed something more than prayer.

This isn’t love, this isn’t normal

Chicago-based therapist Tonia Garnett has traumatic ties to domestic violence. She lost her sister Kimberly to it.

Before Kimberly died, Garnett sensed that something wasn’t right. Kimberly never had access to her money or car and she couldn’t go out as she pleased.

At the time, Garnett was taking a 40-hour course on domestic violence. Garnett said that course caused the puzzle pieces to fall into place. The first lesson described the characteristics of a perpetrator and Garnett immediately drew a connection to Kimberly’s abuser. But before a plan could be fleshed out, Kimberly was caught in a vulnerable state and murdered by her abuser.

“I had to find a purpose behind the death,” Garnett said.

She started working at a domestic violence emergency shelter while still attending her sister’s trial. Garnett has since founded the Kimmy G Foundation in honor of her sister to provide therapy services to domestic violence victims and women who’ve experienced trauma.

After COVID-19 hit Cook County, Garnett transitioned to seeing clients remotely. Surprisingly, she has noticed an increase in referrals since March. Garnett assumed that victims would be too consumed with safety concerns and other virus-related stress to dedicate time to themselves. She attributed the greater volume of referrals to the uncertainty associated with COVID-19.

She said she imagines that victims or survivors feel very entrapped, especially if they had pondered leaving or were in the process of preparing to leave their abuser. Garnett said a woman is actually ready to leave her abuser when she makes a firm decision to leave, begins to prepare and feels it is safe to do so. COVID-19 may unfortunately heighten that threat of harm, especially given that the dire economic situation has left many financially strapped.

She also asserts that leaving often requires a drastic change in routine. That could mean going to a shelter, as opposed to a friend’s house where the abuser can find her, or obtaining a protective order. Changing her phone number, where her kids attend school and where she works, however, are other necessary routine changes that may not be possible right now.

Quarantine or not, Garnett emphasized that leaving a relationship is not as simple as it seems.

“You don’t know how you’re going to respond to somebody that you really love and invested time with,” she said. “It’s not easy to just walk away.”

On top of that, there can be a feeling of disbelief, Garnett said.

“Perpetrators groom their victims,” she said. “In your mind, that first hit is like, ‘Did he really hit me? He didn’t really hit me. Did he really mean that?’”

And with the virus, the victim or survivor may also be concerned about the abuser getting ill if she were to kick him out of their shared residence. The care for his safety doesn’t just disappear.

The complexity of leaving is particularly heightened for black women. If a black woman chooses to date a black man, then she is thought to be asking for the abuse she endures because of the notion that all black men are violent and criminal, Garnett said.

In turn, the black victim or survivor may reason, “I don’t want to put my man in the system or fit the stereotype” and try to handle the violence internally without involving the police, Garnett said.

Even if the police are called, they won’t show up to some neighborhoods. Garnett recalled a specific client who did call the police and was met with, “Hey, go walk around the block and come back.”

In addition to the societal barriers of leaving a toxic relationship, Candace has also dealt with numerous emotional and financial barriers, which has left her feeling overwhelmed.

“I will say that I’m farther than I’ve ever been before,” she said. “No matter how much I lose, I don’t regret the decision of getting me and my children out of this situation.”

Once Candace survives this, she intends to tell her story. She said she wants to help someone else to recognize that these relationships aren’t loving ones, that they aren’t normal.

Sharing her story

That is exactly what Kelly Sundberg, the author of “Goodbye, Sweet Girl: A Story of Domestic Violence and Survival,” has done.

Like Candace, Sundberg was hesitant to label herself a victim because the stereotypical victim is weak-willed or passive. In reality, Sundberg said that stereotype is false. While Sundberg suffered abuse, she said she was strong-willed and fought to fix her marriage on her own. Once her ex-husband began hitting her every week, though, she said she had to accept that she was a victim of domestic violence.

She divorced her ex-husband nearly seven years ago, but the emotional trauma persists. Sundberg said she struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder and came out of the relationship a different person. She said she trusts others, but doesn’t extend that trust to herself.

“It’s hard for me to trust myself because I trusted him,” she said. “And he turned out to be a total monster.”

For the duration of their marriage, Sundberg said she believed her ex-husband couldn’t control himself, and that explained how he treated her. Looking back, she realized the opposite was true. He wielded total control.

“If he just had a rage problem, he would’ve been angry everywhere,” she said. “But he never yelled at his boss, he didn’t yell at his mom — he knew where to direct his abuse.”

Sundberg said her ex-husband suppressed her emotions, which she has since identified as a means of control in her marriage. Social distancing can be restricting, and Sundberg said she empathizes with victims or survivors who are not allowed to take care of themselves and express their full range of emotions during this time.

If she was still enduring domestic violence during the pandemic, she said she wonders whether spending all of her time with her ex-husband would’ve pushed her to leave the relationship sooner.

She hopes that people in the early stages of an abusive relationship who ended up confined with their partner might recognize red flags and therefore be motivated to leave their partner sooner.

“When I was younger, I would’ve said that domestic violence can happen to anyone,” Sundberg said. “But I also would’ve thought in my head, ‘But it won’t happen to me.’ And it did happen to me.”

Email: [email protected]