Football: How Northwestern football handled the 1918 influenza epidemic

April 7, 2020

When the 1918 Northwestern football team had its first scheduled practice on Sept. 16, the team already knew it was destined to have an unusual season.

With World War I the main focus of the country, college athletics took a backseat on campuses nationwide. Although teams could still play, there were restrictions on travel and practice time that limited the amount of practices and games teams could get in.

But the Great War wasn’t the only international event that caused college football in 1918 to look different. As the influenza epidemic grew across the United States, it forced even more changes to the sport.

And as one of the weirdest college football seasons in history unfolded, a solid Northwestern team was right in the middle of it all.

“The football season of 1918 was one of the most peculiar in the whole history of the game,” legendary football figure Walter Camp wrote in the Spalding’s Official Foot Ball Guide, “and yet it will stand as an epoch-making one in the progress of the sport.”

WWI causes changes to college football

Heading into the fall of 1918, the fate of college football was very uncertain. With the creation of Students’ Army Training Corps — of which many football players were members — and the strict limits placed on their time, it was unclear whether there would be enough time and people for sports.

In late September, the War Department gave college football its blessing to continue, but not in the way it had operated previously.

“Sports will be run as an adjunct of military development and not as the main issue of college life, as has been the case in many institutions in past years,” a member of the War Department committee on education and special training said at the time.

The government did this by establishing universal rules on what football teams could do during the season. They decided to allow only 90 minutes of practice time per day, down from the many hours teams had previously spent. The government also implemented travel restrictions, allowing no overnight trips in October and forcing a lot of games between teams far apart to be canceled. In November, squads could make only two overnight trips.

Like every team across the country, the Purple — NU’s nickname during the time period — were greatly affected by the introduction of SATC and the government’s rules. Its schedule was changed and condensed, with an Oct. 19 battle against Ohio State — a budding rival during this era — having to be scrapped.

NU’s practices were scheduled for 4:30 to 6 p.m. Coach Fred Murphy instituted a two-practice system, where players in the downtown schools practiced in Chicago with one coach while students in Evanston practiced with another. And one day during the last week of October, five players left the team when they were sent to service camps.

Even with all these changes, a somewhat normal season could have been played. But the influenza made that impossible.

Breakouts in the Chicagoland area

As the government gave its approval to college football, the second threat to the season emerged.

The first infections in the Chicagoland area occurred at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station in Lake County. And then just four days after Northwestern’s first practice, the Chicago Tribune reported that “Spanish influenza, the new undesirable in Chicago’s midst” had been found in two Northwestern dorms. Less than a week later, there were already 30 to 40 cases in Northwestern’s SATC program.

Cases in Evanston and the Chicagoland area only continued to rise. On Oct. 9, Evanston reported about 300 new cases over a 48-hour span.

Although slow to start instituting measures to curb the outbreak, officials ramped up policies on Oct. 11, banning public dancing across the state. Five days later, all social public gatherings — from games to club meetings — were banned, although saloons and bowling alleys could stay open if they were properly ventilated.

During this time, students faced many restrictions. Trips to Chicago were forbidden. Churches, theaters and other gathering areas in Evanston were closed. University administration even prohibited hangouts in dorm rooms. The punishment for failing to adhere to these guidelines was shrouded in mystery, although the administration said the punishment would “insure obedience.”

“For once in their lives,” The Northwestern Weekly wrote, “N.U. students have not only been willing to attend classes, but thankful for the permission to do so during the past weeks.”

The Purple deal with the epidemic

Northwestern had planned to open its season against Knox College on Oct. 12, but the game was canceled as the city went into quarantine following the major outbreak.

“The Midwestern college football schedule for this afternoon bears a striking resemblance to the remnants of the tattered and torn Hindenburg limb after the allies had messed it up,” the Chicago Herald and Examiner’s Matt Foley wrote.

On Oct. 17 — one day after all nonessential public gatherings were banned — NU held its first intrasquad scrimmage. But the next day, the entire team went into quarantine after George Geiss came down with the flu. He was the second member of the team reported to get sick after assistant coach Jack Ulrich, who had already missed 10 days due to the flu earlier in the month.

Having not rescheduled a game for Oct. 19, NU was now scheduled to open against Michigan Agricultural College — now Michigan State University. The Aggies, who were not members of the Big Ten during this time, had been smacked 39-6 by the Purple in 1917.

But the game, like every contest across the country that weekend, was far from guaranteed. On Oct. 23, Murphy was reported to have “high hopes” the game would happen, despite Evanston still barring athletic contests.

His high hopes proved to be futile, as the game with the Aggies — who had four players with the flu, according to the Detroit Free Press — was canceled.

With less than two days to lock in a new opponent, NU found a challenger in the Great Lakes Naval Training Station. The game was scheduled for 2:30 p.m. at Great Lakes with free admission. Commander John B. Kaufman, athletic officer at the camp, said there was no danger to the public despite the game taking place at the location of the initial outbreak.

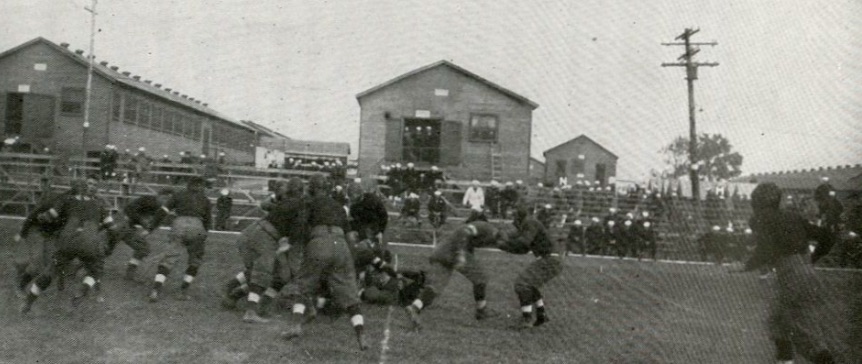

In the game, which some called the best of the weekend, NU and Great Lakes played in “one of the hardest fought games imaginable,” according to The Chicago Tribune’s Walter Eckersall. Amidst a pool of mud, the teams battled to a 0-0 tie. The Bluejackets, who were led by former Northwestern star Paddy Driscoll and future Chicago Bears owner George Halas, would go on to finish without a loss and win the Rose Bowl.

Finding an opponent for Nov. 2

The impact of the influenza on the Purple peaked with the lead-up to the first Saturday in November.

Northwestern was initially scheduled to play Michigan on that date. But in early October, it was reported that administrators were discussing a multi-week, multi-team schedule switch that would have resulted in Michigan traveling to the University of Chicago and Iowa facing NU on Nov. 2. The switch, however, was never approved.

On Oct. 23, the Michigan State Board of Health announced it would not allow the Wolverines to travel to Evanston on Nov. 2, and the game would have to be canceled. When the news arrived in Ann Arbor, “gloom, great oozy gobs of it, settled down on Michigan,” as the Wolverines were hoping to exact revenge after losing to NU in 1917.

The Purple then went searching for an opponent, and seemed to find one in Ohio State. On the day the game was finalized, the state health commissioner banned athletic contests in Chicago and downstate Illinois for the weekend. However, he refused to make any ruling about Evanston, leaving the decision up to the city’s health director. On Oct. 30, Evanton’s health commissioner announced the game would be permitted and that the danger of the spread of influenza in Evanston had passed.

But then health authorities in Columbus decided they would not allow the Buckeyes to travel, and the game was called off. With only about a day to find an opponent, the Cats scheduled the United States Auxiliary Naval Reserve School — a military service academy based in Chicago known generally as Municipal Pier.

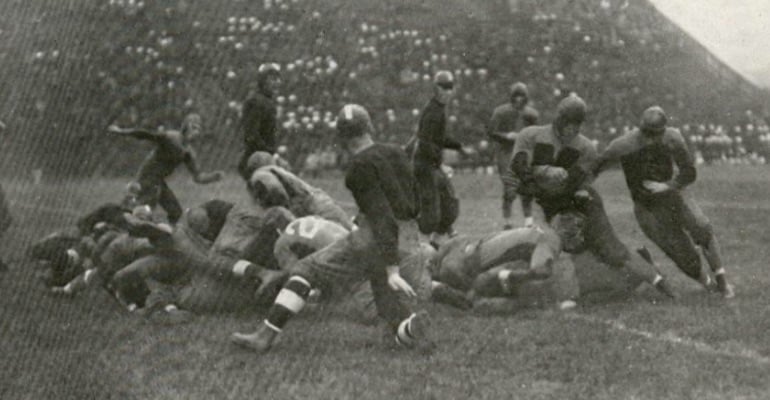

Much like the contest the week prior, the game was regarded as one of the most exciting in the country heading into the weekend. But the result was far different as the visitors dominated the contest, winning 25-0. The Pier would finish the season undefeated.

A season for the history books

The ban on sports in Chicago was lifted on Nov. 4, which included the removal of regulations on attendance as well. After this, football returned to normal.

“Influenza did more to knock it out than did the war,” Camp wrote, “and by November, there was more football played than ever in the old days when the colleges monopolized the sport.”

After the game against Municipal Pier, Northwestern did not face any challenges as a result of influenza. The Purple blew out Knox College the following Saturday 47-7 in Evanston. NU then claimed a huge 21-6 victory over rival Chicago before losing the final game of the season to Iowa to finish 2-2-1. Only once since 1890 has the Purple played in fewer than the five games they played in 1918. That was 10 years prior in 1908, when the team returned to varsity status after a two-year absence with a four-game schedule.

With the COVID-19 pandemic causing the cancellation of winter and spring NCAA championships and the majority of spring seasons, it could be easy to draw some parallels between the situation now and the 1918-19 influenza epidemic in regards to sports. And some of those comparisons are valid.

But, for the most part, the two will yield totally different results. While the 1919 Stanley Cup Final was the only major sporting event to be canceled due to the influenza — and that was after playing five games — there are a plethora of professional sports that are currently suspended and on the verge of being canceled in 2020. Already, the novel coronavirus has altered the sports world in the United States more than the influenza did over 100 years ago.

Still, the 1918 season is one of the most unique in the history of college football. And exploring how the sport, and Northwestern, operated during this time illustrates the challenges of trying to play sports with an infectious disease out in the world.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @thepeterwarren