Food poisoning, the end of a dynasty and the 1959 Northwestern-Oklahoma football game

November 8, 2019

Football

It was the biggest game of the 1959 college football season’s opening weekend.

No. 2 Oklahoma — a national powerhouse that had lost just two games over the previous five seasons — was traveling north to Evanston to face off against No. 10 Northwestern, and NBC was broadcasting the game across the country.

But what they televised wasn’t just a football game. Instead, it was a chapter of one of the most interesting and long-lasting mysteries in the history of college football.

“When you’re that age, I would have been 19 years old, it’s surreal,” former Oklahoma end Paul Benien told The Daily. “You dont think something like that is going to happen to you.”

On the Thursday before the game, half of the Sooners’ travelling team got food poisoning at the Chez Paree — Chicago’s top nightclub — with six spending the night in the hospital. The two teams played less than 48 hours later with the Wildcats smacking Oklahoma by 32 points in a rainstorm. The Sept. 26, 1959 game marked the end of the Sooners dynasty and the boosting of NU to the top of the college football world.

The cover of the 1959 Northwestern-Oklahoma game program.

But questions about the poisoning continued to linger even after Oklahoma returned to Norman. And now, 60 years later, the case file on the Sept. 24, 1959 food poisoning has never been closed.

Kenneth Rudeen, a writer for Sports Illustrated who later became the magazine’s executive editor, perfectly summed up what happened that week in a story written two weeks later.

“It started as a slight case of poisoning and ended as a slight case of murder.”

The Powerhouse and the Upstart

You couldn’t talk about college football in the 1950s without talking about Bud Wilkinson and the Oklahoma Sooners — they were the undisputed team of the decade. From 1950-1958, the team finished the season below No. 5 in the polls just once, won every Big Seven Conference title, made four bowl games and earned three national championships. But the team’s biggest accomplishment was winning a major-college record 47 straight games from 1953-1957.

“Oklahoma during those years had exceptional talent,” said Jay Wilkinson, Bud’s son, who grew up watching the Sooners play. “They had speed and they had discipline. Oklahoma’s great teams were very fine defensive teams. My dad always felt that the order of importance in coaching started with defense, second was punting and third offense.”

If Oklahoma defined college football in the 1950s, Northwestern wasn’t even in the dictionary.

In 1959, the Wildcats were just 10 years removed from their first Rose Bowl title, but it felt much longer. Bob Voigts, a former Cats All-American who coached NU to the Rose Bowl, resigned following the 1954 season after three straight losing seasons. Lou Saban replaced Voigts, but his team went 0-8-1 and his entire staff was fired after the season.

Athletic director Stu Holcomb then hired Ara Parseghian, the head coach at Miami-Ohio at the time, to lead the team. After a .500 season in 1956 and a putrid 0-9 campaign in 1957, Parsegihan and NU turned the boat around in 1958. The team finished 5-4, defeated two ranked teams in Ohio State and Michigan and, at one point during the season, rose to No. 4 in the AP Poll.

“You always think you have a pretty good team,” said Dale Samuels, an NU assistant coach from 1956-59. “(In 1958), we were close in all the games we played. We looked forward to the 1959 season — opening up with Oklahoma was as tough as it gets.”

Thursday night at the Chez Paree

Oklahoma arrived in Illinois earlier than usual, flying on Wednesday night instead of Thursday. The team stayed in the Orrington Hotel — the current location of the Hilton Orrington — during their trip and held a secret workout session Thursday afternoon.

After the practice, the team returned to the hotel. On every away trip, Wilkinson and the Oklahoma staff planned a nice dinner at a fancy place near where they were staying. For this trip, they chose the Chez Paree.

The Chez Paree was the nightclub of the 1950s in downtown Chicago. Located at 610 North Fairbanks Court, the club regularly saw some of the biggest celebrities in the country — entertainer Sophie Tucker; singers Nat King Cole, Jimmy Durante, Duke Ellington and Frank Sinatra; and comedian Jerry Lewis.

While most of the coaching staff, including Wilkinson, did not attend, all the players except starters Prentice Gautt and Edward “Wahoo” McDaniel made the trek to the nightclub. The team arrived for their meal around 7:15 p.m., and were greeted by a hostess who asked the players their names and positions.

Oklahoma athletic business manager Ken Farris, who had been planning the event for three months, had chosen the menu for the evening: fruit cup, tossed salad, mashed potatoes, steak, rolls and butter, ice cream.

Paul Benien’s headshot in the Northwestern program.

But the team didn’t even make it to the main course.

“We didn’t know what the heck happened,” Benien said.

The players were served the fruit salad, and only 15-20 minutes after sitting down, some started getting “violently ill,” Benien recalls. He remembers players stumbling down the steps, trying to make their way to the street so they could take taxis to the hospital.

It was a chaotic, scary scene — players vomiting, dealing with diarrhea and nausea. In Jim Dent’s book on Oklahoma football during the 1950s, he wrote that starting quarterback Bobby Boyd lay on the sidewalk outside the building waiting for a cab because he was so sick.

As they drove to the hospital, Benien remembers telling the cab driver to pull over at the median of Michigan Avenue/Lake Road, where players would open the doors and throw up. He said he almost bailed out of the cab three times.

“I threw up four or five times before I went to the hospital,” former tackle Bill Watts told The Daily. “They were pumping our stomachs and everything else. It was a traumatic experience.”

Eight players — along with assistant coach Jimmy Harris — spent time at the hospital: co-captains Gilmer Lewis and Boyd; starting center Jim Davis; backups Bob Scholl, Bob Page, Ronnie Hartline and Benien; and Watts, a third stringer. Only Watts and Hartline returned to the hotel by the end of the night. The rest had their stomachs pumped, while Page suffered a circulatory collapse.

The six hospitalized players were released on Friday around noon, Benien recalls. When he returned, there was a whole new atmosphere around the team.

“We were supposed to have some team meetings and things like that on Friday and have another dinner and probably go out to a movie, but most everybody went back to (their) hotel room and that was it,” Benien said.

A blowout in a monsoon

Benien remembers sitting in the Dyche Stadium locker room before the game. He recalls it being “pretty dreary” and that there wasn’t “a lot of enthusiasm.”

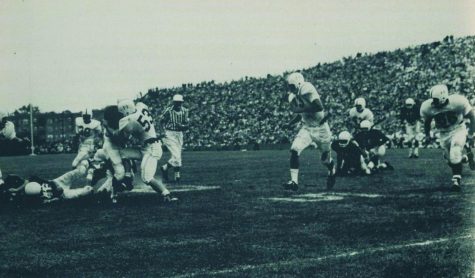

Ron Burton carries the football in the 1959 Northwestern-Oklahoma game.

From the moment the game started, NU imposed itself as the stronger team, scoring on two early rushing touchdowns. At the start of the second quarter, a massive rainstorm that swept through Evanston was so powerful that many people watching the game on television were unable to see the action on the field. NU dealt with the weather better than its opponent, and when the rain stopped and the grass was an Everglades swamp, the Cats kept dominating — eventually claiming an assertive 45-13 victory.

It was the worst loss in the Wilkinson era. Boyd called the team’s performance “pitiful.” The Sooners fumbled the ball 11 times, losing five. They were sloppy and got thoroughly outplayed.

Mike Stock, a junior fullback and captain on the 1959 NU team, said the Cats were extremely prepared for Oklahoma’s high-tempo offense and that victory was critically important for the program.

“Doing things like that, that’s a shot heard round the world,” Stock said of the game. “That was huge.”

Who did it?

In his book on the Wilkinson era, former Oklahoma sports publicist Harold Keith recalls a story from Sept. 24, 1959 when he received a phone call from Fred Russell, a prominent sports reporter. Russell said the point spread in favor of the Sooners had been slashed in half, and asked if there were any injuries. Keith said there wasn’t.

Then the team went to the Chez Paree.

In the immediate aftermath, investigators tested the team’s meals from that Thursday. Dr. Edward Press, Evanston’s health commissioner, inspected the sandwiches served for lunch at the Orrington, and Dr. Herman N. Bundsen, Chicago’s health director, looked at the food at the Chez Paree.

A sketch of the Orrington Hotel.

In one of Press’s tests, a bacteria that can cause upset stomachs turned up on the turkey used for the sandwiches. However, those symptoms would show up within two hours, and Harris did not have a sandwich for lunch. That eliminated the Orrington.

It had to be the Chez Paree.

But Bundsen said the Chez Paree food did not test positive for poisoning. That answer didn’t satisfy Oklahoma. The fruit salad served at the Chez Paree was the only logical answer.

Oklahoma’s team physician wanted to do more tests on evidence secured at the hospital, but the hospital said they lost the files.

“When the Oklahoma medical team insisted on the hospital preserving (the collection of files) for them and having it mysteriously disappear,” Jay Wilkinson said. “It’s really sad in the history of sports that something like that would happen.”

Even without the files, Oklahoma officials reached the conclusion that the players received food poisoning from the apomorphine in the fruit salad. And the team also came to the conclusion that gamblers and/or the mob poisoned them, which would account for the point spread dropping the day of the poisoning. They concluded that those who knew about the poisoning beforehand put a lot of money on the Cats, causing the line to drop so rapidly.

Bud Wilkinson played down the event, both in the media and within the team, because he was not the type of man to make excuses. He said his team was beaten not because they were poisoned, but because NU was the better team.

Watts said the game probably should have been cancelled and that while people said there would be a big investigation, there never was.

“They didn’t pursue the investigation too vigorously because they also thought, ‘What mother is gonna say okay my kid wants to go play at Oklahoma, he might get drugged and poisoned over a football game,’” Watts said.

One person who did investigate was Tim Cohane, the Sports Editor of Look Magazine and a good friend of Wilkinson’s. According to a 1997 article from the Tulsa World, Cohane’s investigation was “persuasive” in tying gamblers to the poisoning, but the magazine’s lawyers thought it was “too risky to publish.”

The Daily reached out to the family of Cohane, asking if they had any information on his investigation. Cohane’s son said he looked through his dad’s files but couldn’t find anything.

While there is no public information about the planning behind the 1959 poisoning, there is a record of a poisoning in 1954.

Steve Budin is the son of a New York bookmaker. In his 2007 book “Bets, Drugs, and Rock & Roll,” Budin describes a situation in 1954 involving Oklahoma and Oklahoma A&M — now Oklahoma State.

Budin says his father worked with a “legendary figure named J.R.” in the Chicago area who was connected to the mob. During the week of the 1954 game, Budin’s father got a call from J.R. telling him to bet as much as he could on A&M. J.R. had never not told him a specific number.

A short-handed Oklahoma team played that Saturday as many players on the team got sick. J.R. told Budin’s father that his guys went to the hotel the Sooners were staying at before the game. The guys beat up the cook, according to J.R.’s account, then gave him $100 to pour horse laxative into the soup that the players later ate. Oklahoma won, but did not cover the spread.

Budin then says that J.R. and his partners reportedly did the same thing for the 1959 game, although he does not chronicle the story in his book because his dad did not work with J.R. at the time. But, the story illustrates how one could — and did — successfully poison a football team once before.

And that they could do it again.

Impact on the programs

The game was a crucial marker for both the NU and Oklahoma programs. NU proved to the country it was for real. The Cats jumped to No. 2 in the polls and then travelled to Iowa City the following week and beat No. 5 Iowa to prove their might. But quarterback Dick Thornton was injured in the game, and NU wasn’t the same.

“Had (Thornton) not gotten hurt early in the year,” Samuels said, “that team had every possibility of going undefeated.”

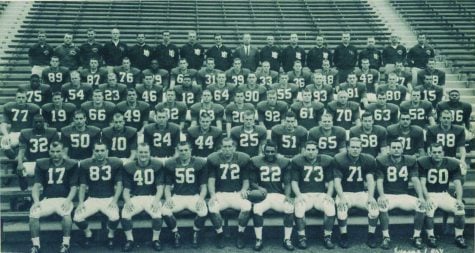

The 1959 Northwestern football team.

Led by halfback Ron Burton — who was named a consensus All-American at the end of the year — the Cats managed to win their next four games before crashing at the end of the season with three straight losses.

NU travelled to Norman for a rematch against the Sooners in 1960 and proved 1959 — poison and all — wasn’t a fluke. Despite extremely warm temperatures, the Cats cruised to a 19-3 victory.

Oklahoma wasn’t the same after the NU game. While there were signs that forewarned of a demise, that contest is known as the moment that Wilkinson era went into a sharp decline. They finished the season 7-3, but fell to 3-6-1 in 1960 and then 5-5 in 1961.

For the Sooners, Sept. 26, 1959 was the day the dynasty died.

“I wish they would throw the (NU game out of the record),” Benien said, “but they’re not going to. Football is football.”

Still unsolved?

Mostly everyone involved in the incident believes that gamblers and/or the mob committed the poisoning.

“It was not a gray situation,” Jay Wilkinson told The Daily. “There are just so many indicators to this story that point to some nefarious play and bad intentions on the part of certain people.”

However, barring a breakthrough, the full truth of what happened that Thursday night at the Chez Paree will probably never fully be revealed.

It is worth noting that there has never been any suggestion that NU had anything to do with the poisoning. In fact, Benien and Wilkinson both gave credit to the Cats football team in their interviews with The Daily, praising Parseghian and the team that year, while emphasizing that they weren’t involved.

Despite its relevance at the time, the incident is not a well-known event in college football history. But it’s a key moment in Oklahoma’s and NU’s history, as well as a fascinating tale about a historic era of the sport.

For the athletes who played in that game, they have all moved on. Benien said he still gets together with his old teammates, grabbing dinner and talking shop. Naturally, they reminisce about the old days, but does the poisoning ever come up?

“No,” Benien said with a laugh. “We would like to keep it out of our minds.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @thepeterwarren