Doing double: Ethnic studies programs — suffering funding and faculty dearth, high turnover rates, intense working conditions — demand structure reform

May 30, 2019

Hamstrung by a lack of departmental status, Northwestern’s ethnic studies programs have – until recently – been barred from hiring tenure-track faculty exclusive to their fields, leading to a turnover crisis.

IT’S HARD ENOUGH being a professor in just one department. Imagine doing it all twice: Double the meetings and students; double the conferences to travel to and research papers to edit; double the energy, time and service. In essence: Double the labor.

For years, doing double has been routine for faculty in ethnic studies programs at Northwestern, and for their peers across the country. Hamstrung by a lack of departmental status, Northwestern’s ethnic studies programs have — until recently — been barred from hiring tenure-track faculty exclusive to their fields.

The result has been massive turnover. Like moving through a revolving door, professors from across the country have cycled through Northwestern’s ethnic studies programs, hired on ultra-short, non-renewable contracts that have left them all but poached. It’s why Associate Prof. and Director of Asian American Studies Nitasha Sharma said the program has been forced to initiate ten new searches for professors in just the past five years — all hires who have since left the University.

Sharma said the 100 percent faculty turnover rate isn’t surprising: Why invest so much in a job that may not even exist in two years? Professors, understandably, want tenure, she said. So when other universities are able to offer that, it’s not hard to see why department-exclusive professors — who Sharma said are often overworked — make the jump.

For program faculty who do have tenure, it’s because they’ve been required to share appointment in a separate department — a tenure home — according to former Latinx Studies Prof. Frances Aparicio. That home can be anywhere, Aparicio said, so long as it’s in a department (for Aparicio, it was the Department of Spanish and Portuguese). But in turn, practically all long-term ethnic studies program faculty have had no choice but to split responsibilities among two areas of study — so far, that’s been the only way for program faculty to become tenure-eligible.

“All four tenure-track professors in Asian American Studies have 50 percent appointment within in Asian American Studies and 50 percent in a tenure home,” Sharma said. “What that means is that every single person hired in the ethnic studies — we have do twice the service, twice the labor, twice the meetings, twice the students compared to anybody who is a 100 percent hire in English or a 100 percent hire in history, for example.”

Ostensibly, things are changing: Aparicio said after rounds of negotiations with Weinberg Dean Adrian Randolph, ethnic studies programs — including the Asian American Studies (AASP) and Latinx Studies (LLSP) — won the ability to hire tenure-track faculty 100 percent exclusive to those programs, before a power only afforded to departments. Aparicio said the change holds the potential to lower turnover rates and help the University build robust ethnic studies programs.

But students and program faculty aren’t so sure. Despite recent reforms, the formation of a slew of search committees and verbal commitments to fortifying ethnic studies, community members still express a glaring gap: the lack of formal creation of an Asian American Studies or Latinx Studies department.

That distinction — between program and department — may seem trivial, even bureaucratic. But it’s at the center of a years-long fight waged by faculty and students alike in the name of ethnic studies. And people want to know when things will finally come to a head.

Work, Times Two

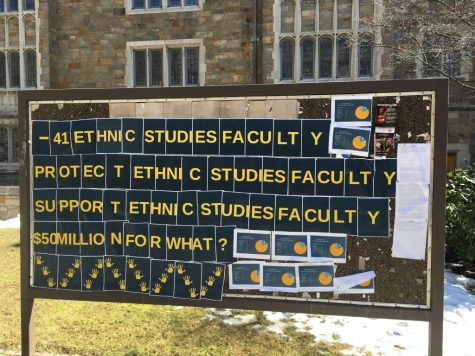

CONFLICT OVER ethnic studies isn’t unique to Northwestern: Fights for departmentalization are unfolding across the country, Aparicio said — most recently at Yale, where in a mass demonstration, thirteen professors withdrew from the university’s ethnic studies program, condemning the college’s failure to adequately support it.

A sign at Yale University.

Ethnic studies faculty at Northwestern have expressed similar concerns. Sharma said the lack of exclusive tenure-eligibility within the Asian American Studies Program, for instance, has overburdened professors of color, who are overrepresented in the ranks of AASP faculty, and lowered the quality of education — disproportionately hurting already-marginalized groups on campus.

The lack of departmental status “contributes to the nationally recognized phenomenon — as studied by researchers — that women and people of color who are in the academy tend to do more service,” Sharma said. “We know that women and minority faculty get paid less than white men on campus, so you’re doing more work; you’re split between programs and departments; you have to be legible in your department not your program; and then you’re doing 200 percent labor for less money.”

Students lose because of this too, Aparicio said. When professors have to divide all their time between two departments, there’s less time to build strong curriculums and mentor students, she explained — they get burnt out.

That’s why, for many ethnic studies activists, the defense for keeping AASP and LLSP programs rests on a shaky pretense. As Sharma explained, it’s not that ethnic studies programs courses are unpopular — in fact, they consistently fill up. But because program professors are forced to find tenure-home in other departments, Sharma said, AASP faculty, for instance, are limited in the classes they can teach to begin with.

“When you’re a director of a program, you get a two-course release, meaning that any faculty who is director of a program, they’re teaching two classes that whole year — one of which is supposed to be for their home department, leaving one class for Asian American studies,” she said. “What does that means for students? If I’m teaching one class or two classes a year in Asian American studies and my colleagues are doing similar, that leaves tenure-track faculty teaching like five classes a year when we need like sixteen a year.”

Furthermore, in many cases, program faculty don’t even know the classes until the last minute — making scheduling difficult. Aparicio said many of her tenure-track LLSP colleagues had to wait until they found out their departmental course responsibilities before committing to Latinx studies classes, reducing program autonomy and hampering self-determination.

To bridge the dearth of available faculty, the University has, thus far, turned to contingent faculty, hired on short-term arrangements. But with few rights and no tenure potential, turnover rates have been high, and as such, they’ve left — leaving in their wake human-strapped ethnic studies programs, run by super-small teams of overworked faculty of color.

Notably, this is not to say that AASP or LLSP has been unable to contribute to the academic ecosystem at Northwestern, nor that the fight for ethnic studies has been victory-less, professors emphasized. Much to the contrary: Despite constraints, Sharma said the Asian American Studies Program routinely puts out strong scholarship and boasts brilliant, award-winning faculty. And in just the past few years, the Latinx Asian American Collective, a student-activist group, has pushed for AASP to receive a major track, and created conditions for exclusive, tenure-track hires within programs.

“Latinx Studies as a program was able to make its own hire into Latino studies this year, and that was the first one we’ve ever made,” Latinx Studies Prof. Geraldo Cadava said. “So that signals a shift by the college to allowing programs to do their own programs in a way that they’ve never been able to do before.”

‘We don’t know’

AND STILL, those changes may be too little, too late.

Sharma said while being able to hire within programs is a step forward, it is by no means the end of the road. That would be departmentalization.

“This is excellent. This is wonderful. We’re also really pissed off,” Sharma said. “A, the students are really pissed off because they really haven’t been a part of any of this process. B, they’re pissed off because this victory doesn’t mean departmentalization. This still means that the programs get to hire, but it doesn’t address the students’ concerns. They want graduate students, they want more mentorship, they want more availability of faculty, they want a department.”

Becoming a full department, Cadava said, would offer ethnic studies programs “real seats of power at the University.” He said departmentalization would have significant implications in terms of funding for LLSP, allowing for more programming, research and even potentially the formation of a PhD program.

That’s why, even despite recent wins, ethnic studies activists are not appeased, and the debates are not over: They want departmentalization.

Student activists of the Asian American/Latinx collective discuss.

Beyond programmatic concerns, faculty wonder whether even these promises — for more exclusive ethnic studies professors — will come to fruition.

“I still think that there are still lots of open questions about how many faculty we would be able to hire,” Cadava said. “How many (hires) of Latinx Studies professors would we be able to control if we were to become a department, compared with remaining a program? It’s all brand new — we don’t know.”

Aparicio said while there are no formal “quotas” on the number of new hires, it’s unclear how fast the University will make headway on appointing new faculty. She said the University has received a Mellon grant — to the tune of $2.5 million — presumably to aid in the hiring process. But even that is up in the air.

“The dean’s office says they have applied for and won … a 2.5 million dollar Mellon grant that me and the former director of Latinx Studies were only informed of through The Daily,” Sharma said. “When I asked the Dean for a copy of the Mellon proposal, they refused to give it to me — so AASP/LLSP have no idea what the funds are for or how we can use them in order to advance these programs for the students. That baffles me.”

Weinberg Dean Adrian Randolph didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Making things worse, if AASP/LLSP remain programs, they’re forced to go through incredibly elaborate processes to appoint tenure-track faculty under the current structure. Sharma said only three AASP professors are tenured, and all three of them are required to agree on any future tenure hire — something which would take an enormous amount of “human power.”

Aparicio said she’s grateful for the progress programs have seen recently, and specifically noted how helpful Provost Jonathan Holloway has been in facilitating the process. But because of these concerns, she said she still “would advocate for full departmentalization.”

In an interview with The Daily, Holloway recognized there’s a “long history of faculty” hailing from ethnic studies programs “feeling under-resourced.” But he said there’s many potential explanations for those sentiments, and said he doesn’t “know enough” about whether it’s lack of departmental status specifically that’s driving Northwestern faculty to “come or go.”

Valuing ethnic studies

IN THE MIDST OF THIS BATTLE ARE students, who in recent years have mobilized aggressively for departmental status. As a result of activism by the Asian American Latinx Collective, the University has recently put together a search committee called the Intercultural American Studies Council that will conduct faculty searches to appoint tenure-track professors for the Latina and Latino Studies and Asian American Studies Programs.

Cadava said this battle has largely been “student-led,” but despite that, the students aren’t placated. Instead, many feel alienated and left out of recent conversations.

Weinberg junior Isabella Ko said departmentalization isn’t just an academic concern — strong ethnic studies programs have reverberatory effects across communities on campus.

“At the core, this is about the knowledge that is being valued, the work that is being valued, the histories that are being valued,” Ko said. “Even though I’ve basically never taken an Asian American studies class, I still gain so much from that program.”

Ko said she isn’t satisfied with the University’s responses and that it’s “unfair” that it expects full-time students — who don’t know the intricacies of academic bureaucracy — to navigate a fight like this, just to see their cultures represented and “valued.”

To Sharma, the devaluation of ethnic studies is a historical phenomenon — and without radical, structural change, she said it’ll continue.

“At Northwestern you have this focus on ‘diversity and inclusion’, which is ironic because Northwestern has been an explicitly exclusionary space,” she said. “Ethnic studies has always been devalued.”

Email: pbaskar@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @pranav_baskar