In Focus: How the NCAA’s institutional barriers shut out black coaches

May 28, 2019

Editor’s note: When this article refers to Division I schools and their statistics, HBCUs are excluded from the numbers.

When former Northwestern assistant coach Pat Baldwin started playing basketball at six years old, his future career plans were different than most.

While many kids dream of making it to the NBA, Baldwin aspired to be a professional coach. Most young players grew up imitating Michael Jordan or Magic Johnson; Baldwin looked up to the all-time great coaches. He got his first experience coaching children as a high school student.

“I put the towel over my shoulder like John Thompson would back when I was watching the Georgetown days,” Baldwin said of the experience. “At that point, I was emulating coaches.”

After playing college basketball at Northwestern from 1990-1994, it took Baldwin seven years to get a coaching job. Unsure of the best way to break into the field, Baldwin worked in corporate America and played overseas instead.

Baldwin eventually got his first opportunity to coach professionally in 2001 as an assistant coach at Lincoln University in Missouri. He made four more stops as an assistant coach — including in Evanston for four years — before earning his first head coaching job in 2017 at Milwaukee.

Baseball coach Spencer Allen. Across 19 varsity sports, Allen is the only black head coach the University has hired since the beginning of the 21st century.

The road to becoming a Division I coach can be a challenging one, especially for coaches of color. Baldwin is one of 82 Division I head men’s basketball coaches of color in the NCAA, while the number of white head men’s basketball coaches is over three times higher at 249. That disparity widens in women’s basketball, and in football, it’s even more stark: Just 24 of the 232 Division I head football coaches are people of color.

Despite a slight increase in representation over the past 10 years, college athletics as a whole still has a long way to go to provide equitable opportunities for coaches of color, specifically black ones. Even though black coaches have slowly been presented with more head coaching roles, those opportunities pale in comparison to what is afforded to white coaches across the country.

While Northwestern hired two black head coaches in the early 1980s, there have only been three more at the University since 1985. Across 19 varsity sports, baseball coach Spencer Allen — who’s one of three black Division I head baseball coaches — is the only one the University has hired since the beginning of the 21st century.

Setting the standard

Almost 35 years before the Wildcats’ only current black coach was hired, Northwestern hired their first black head coach. They were one of the first to provide a black coach with an opportunity to lead a team.

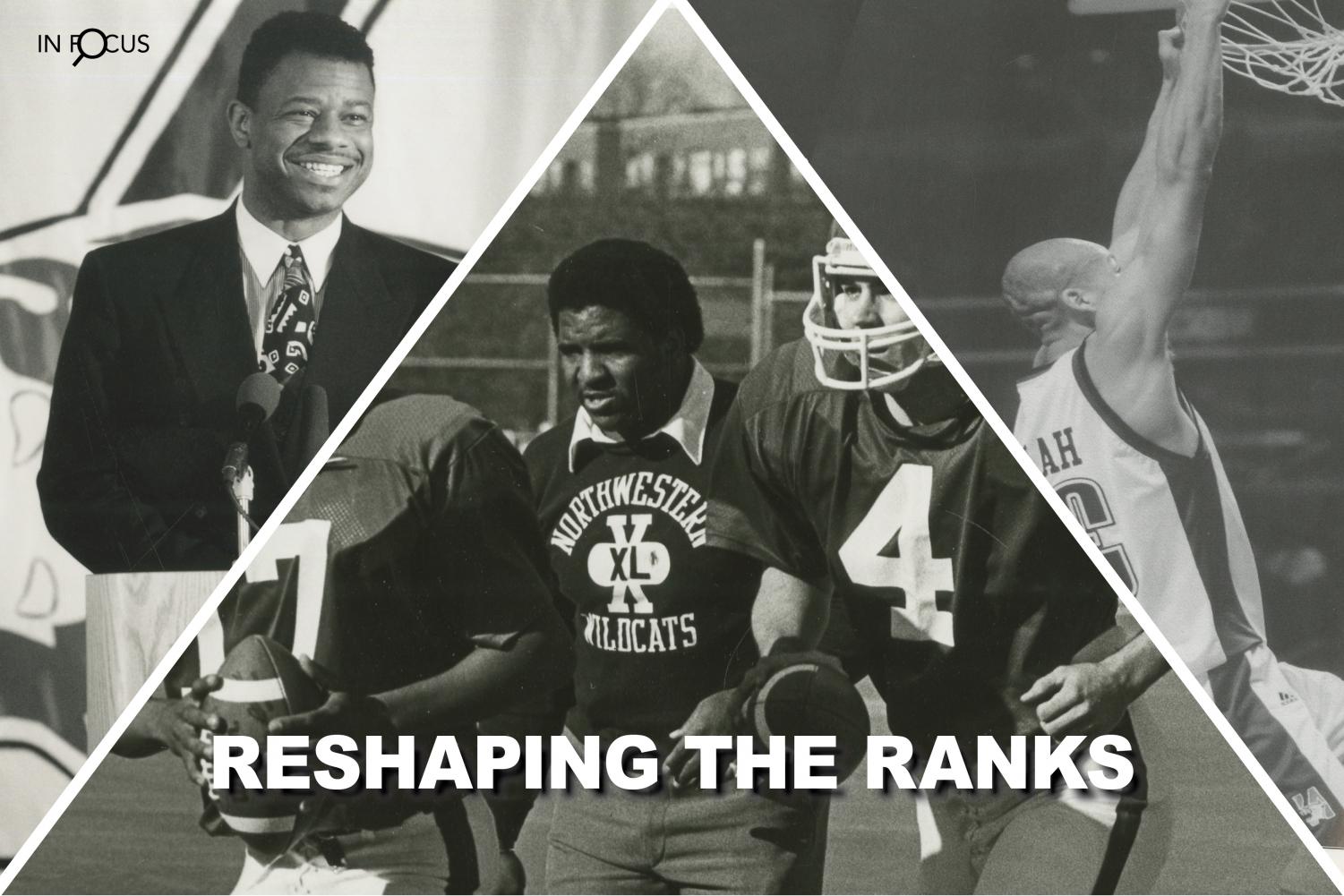

In December 1980, the University hired Stanford’s Doug Single as the school’s new athletic director. As Single moved east, he brought a member of Stanford’s football staff with him, hiring then-offensive coordinator Dennis Green to fill the Wildcats’ head coaching vacancy.

When he took over, Green became the second black head coach in Division I history, providing the country one of its first glimpses at how a top coaching role could be filled by a black candidate.

At Northwestern, he gave black student athletes — many of whom hadn’t had a head coach of color at the college level — a leader who looked like them.

“Typically, to have one black coach on the staff was the norm,” said former Wildcats offensive tackle Chris Hinton. “All of a sudden, Dennis Green comes in and I would think there was probably at least three black coaches.”

As Green started to change the look of the football program, Northwestern also brought in a new face for its track and field program. In 1981, Delores “Dee” Todd was hired, becoming the first black female coach in school history.

Todd coached various high school sports in Maryland and Illinois, but her passion was always track and field. After getting married and moving to Chicago, she heard about the Northwestern opening from the Illinois track and field coach and applied for the position.

Dennis Green (left) stands at the lectern after being hired in 1980 by athletic director Doug Single (right).

When Todd was hired, she took over a program that had finished in 10th place in the Big Ten in back-to-back campaigns. After finishing in the same position during Todd’s first year, the Wildcats saw modest progress in her second season.

“When we went to Big Ten Championships in cross country and finished ninth, you would’ve thought we had won the Big Ten,” Todd said.

And soon those improvements gained momentum: Over the next two years, Todd collected a conference Coach of the Year award and led the Northwestern to back-to-back 5th place finishes at the Big Ten Championships.

In the same timeframe, Green had already begun to leave his mark on the football program. In his second season, Green won Big Ten Coach of the Year after improving the team’s win total by three games.

But by 1986, both coaches were no longer at Northwestern.

Green left Northwestern during that year to become assistant coach for the San Francisco 49ers and Todd left after the 1984 season to coach Georgia Tech’s cross country and track teams. However, Todd said she has nothing but fond memories of her time in Evanston.

“I never felt at all out of place or unwanted or anything at Northwestern,” Todd said. “I can definitely appreciate that school and that conference. They will always be very near and dear to my heart.”

Representation in the Big Ten

While Northwestern might’ve set the bar for hiring black head coaches 35 years ago, the University hasn’t made significant strides since.

Aside from Allen, the Wildcats’ only other black head coaches since 1986 have been Francis Peay and Ricky Byrdsong. Peay was the defensive coordinator under Green and was promoted immediately after Green’s departure. In six seasons, Peay led Northwestern to a 13-51 record before he was fired.

Byrdsong, who took over as the men’s basketball team head coach in 1993, led the Wildcats to a winning record and a berth in the National Invitation Tournament in his first year. But he’d only coach three more seasons before being fired in 1997.

Dee Todd. During her tenure, Northwestern’s first black female head coach took the Wildcats from 10th to 5th in the Big Ten Championships.

Though some older coaches like Todd view the Big Ten as progressive, data show that recently, the conference has dropped the ball when it comes to hiring black coaches.

Last season, the Big Ten had 14 men’s basketball coaches. All 14 were white men. Prior to Juwan Howard’s hiring at Michigan last week, the conference hadn’t seen a black men’s basketball head coach since 2015. The last time there were two or more in a single season was over 10 years ago. In addition, since 2008, the Big Ten’s number of black head coaches in women’s basketball has declined from three to one.

In 2018, three of the Big Ten’s 14 head football coaches were coaches of color and two, Illinois’ Lovie Smith and Penn State’s James Franklin, are black. They have been joined by former Alabama offensive coordinator, Mike Locksley, who was hired by Maryland during the offseason.

Franklin, Locksley and Smith all declined to be interviewed for this story.

Richard Lapchick, the director of The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport, said he believes that the country’s “culture” of segregating minorities leads to unfair hiring practices — and it also applies to coaching.

“Persistent acts of racism and discrimination make it much more difficult to develop and maintain a diverse ‘pipeline’ for minorities to obtain the education, skills and mentorship necessary to be promoted into these leadership positions,” Lapchick wrote in an email to The Daily.

“This is especially true of the very visible and highly coveted positions, such as the football and basketball head coaching positions.”

More than a recruiter

While Green and other black coaches emerged in head coaching ranks in the ‘80s, that didn’t change the fact that coaching staffs often remained predominantly white.

Years before Green was hired, black coaches were seen by some coaching staffs as the primary recruiters of black student athletes. Northwestern was no exception.

As Northwestern began to diversify its football team in the late 1970s, then-head coach Rick Venturi hired Johnny Cooks, a former Wildcats running back who became the only black coach on staff. During Cooks’ time at Northwestern, one of the players he recruited was Hinton.

A highly-touted recruit from Chicago, Hinton went to the predominantly-black Wendell Phillips Academy High School.

While he formed many bonds with Northwestern players and coaches during his recruitment, Hinton said he kept in touch with Cooks more than any other coach.

He added that Cooks was seen by the coaching staff as the primary recruiter of black athletes and said that acting as the “liaison” between black players was an unspoken part of a black coach’s job description. Hinton said he was once told by a former coach that black assistants were often sought out to fill that role.

“He said, ‘When a new coach is hired, one of his first hirings was a black coach,’” Hinton said. “You had to have one.”

More recently, some black assistant coaches have had greater opportunities to contribute outside of recruiting.

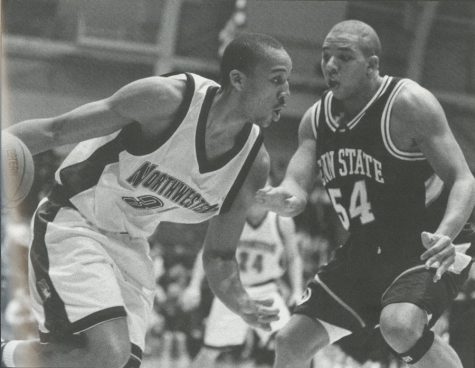

Former Northwestern basketball player Tavaras Hardy dribbles the ball. Hardy returned to Evanston as an assistant coach from 2007-2013 and is now the head coach at Loyola Maryland.

When current Loyola Maryland head men’s basketball coach Tavaras Hardy accepted an assistant coaching job for the Wildcats in 2007, he felt confident. The Joliet native grew up just an hour away from Northwestern, where he committed to play basketball about 10 years prior.

After four seasons at Northwestern from 1998-2002, Hardy found his way back to Evanston as an assistant coach under Bill Carmody after coaching in the AAU circuit. Hardy said he believed his experience as a former athlete would help him recruit players from all backgrounds.

But he also understood the roles black coaches had been relegated to in the past.

“Coach Carmody made it clear to me that he was never going to put me in a bubble,” Hardy said. “(It wasn’t) like, ‘You’re the black assistant, you gotta be the recruiter.’ He said from the get-go, ‘I want you to be a complete basketball coach. I want you to learn how to do everything.’”

Carrie Banks, a former Northwestern women’s basketball assistant coach, said she has also been fortunate enough to not be restricted to recruiting.

Banks coached in Evanston for three seasons before leaving to take an assistant coach position at Ohio State. She said sometimes younger hires do get confined to a recruiting role, but she believes all assistant coaches should be used to impart their knowledge on student athletes in a multitude of areas, beyond just recruiting.

“I hate that,” Banks said about black coaches being seen as solely recruiters. “You just hope that you’re with a program where all of your talents and knowledge are utilized.”

The intersection of race and gender

Some black coaches say there’s another layer to the challenges they face: gender inequality. Many athletic departments also don’t place enough value on gender diversity when bringing in potential candidates for coaches and higher administrative positions. And as a result, the intersection of multiple marginalized identities can often lead to deeper barriers for black women.

Former Wildcats women’s basketball player Anucha Browne has held various high-ranking positions throughout collegiate and professional sports.

She worked at Buffalo, in the NCAA and eventually for the New York Knicks, where she served as the senior vice president of marketing and business operations from 2002-2006. This made her one of the highest-ranking black female executives in professional sports.

During her time working at the NCAA and NBA, Browne said she has seen male administrators who had women’s coaching applications for positions in male sports come across their desks, only to not evaluate them.

Former Wildcats women’s basketball player Anucha Browne in 2007. Browne has held various high-ranking positions throughout collegiate and professional sports.

And that shows up quantitatively: Only 4 percent of Division I head coaches in men’s sports last season were women, and even fewer were women of color.

With an increased number of female administrators, Browne believes that change in hiring practices would start to occur, giving women more chances for positions in and outside of women’s sports.

“The playing field needs to be leveled,” Browne said. “We need to start having the same conversation about women coaching men, women sitting in the athletic director chairs, women sitting in Division I conference commissioners’ chairs. And strong women in those chairs… That’s when you start to see change.”

Of the 130 athletic directors who oversee FBS football programs, there are 100 white men, 11 black men and one black woman. Carla Williams, the athletic director at Virginia, was hired in 2017, becoming the first black woman to lead an FBS athletic department.

At the NCAA headquarters, only five women of color held positions of vice president, senior vice president or executive vice president of their respective departments.

Black women have historically been left out of coaching roles in men’s sports. For example, Maine’s assistant Edniesha Curry is the only black female Division I men’s basketball coach. There has never been a black female head coach in Division I college football and, in the 2017-2018 season, only 15 women held assistant coaching roles — none were women of color.

Even in women’s sports, black female coaches struggle with underrepresentation.

In women’s basketball last season, there were only 56 black coaches, of which 39 were women. One of those was former Wildcats assistant coach Tasha Pointer, who was hired as Illinois-Chicago’s head coach in 2018.

Pointer, who has also been an assistant coach at Rutgers and St. John’s, believes increasing diversity starts at the top. While people know about the low number of black women in coaching, she said it’s important the NCAA recognizes that and takes tangible steps forward.

“With a naked eye, you can almost figure out the stats,” Pointer said. “But then it becomes a matter of ‘How do we make sure that we have diversity?’ How do we make sure that we’re not just hiring for the sake of hiring because ‘I’m hiring a friend’ or ‘I’m hiring, not the most qualified candidate, but I’m hiring from comfort so I hire somebody that looks like me.’”

During her short time at UIC, Pointer said she has tried to make improving diversity a priority. She said she learned from Northwestern athletic director Jim Phillips that diversity and inclusion only comes through intentionality and actively working to make positions accessible for everyone.

“That’s what most people want: a voice and an opportunity to be represented,” Pointer said. “I’m now cognizant of that and not just looking for someone to be a token, but being very intentional about making sure that diversity lives.”

Barriers for young coaches

Pointer said she tries to make a concerted effort to ensure her coaching staff is racially diverse, but institutional barriers make the process more complicated than it may seem.

One way teams attain young coaches is by hiring graduate assistants, but to many, getting there isn’t an easy or accessible path.

Graduate assistants can only coach for two years unless they complete 24 semester hours during that time, which allows them to coach for a third year.

They must also have received a bachelor’s degree and finished their college athletic careers — whichever comes last — and continue to take graduate classes while holding the position.

This system can prove effective for some aspiring coaches out of college, but some say the lengthy requirements also create barriers for those who hold marginalized identities.

Lapchick, the TIDES director, said accessible education is vital to improving diversity in coaching. However, he added that he believes many people of color lack access to quality education in public schools — without that, they face obstacles getting coaching opportunities.

“Removing this barrier provides more people of color with an opportunity to go to college, receive a degree and begin a career that provides focused mentorship and the skills required to be a leader,” Lapchick said.

Even for aspiring coaches with a bachelor’s degree, the challenges during the hiring process don’t disappear.

Growing up, Wildcats running backs coach Louis Ayeni said his parents stressed the importance of education, forcing him to choose Northwestern over other schools because of its academic reputation.

Ayeni made his way to the NFL, where he played for two years as a member of the Indianapolis Colts and the St. Louis Rams, before returning to Northwestern as a graduate assistant.

But for some athletes who want to both play in the NFL and have a future coaching career, serving as a graduate assistant often isn’t a possible route: one is only eligible for the role within a seven-year window of getting their bachelor’s degree or finishing their college careers.

“(It’s) how a number of guys start,” Ayeni said. “If you play in the NFL for seven-plus years or whatnot, you can’t be a GA. Not saying your seven years of experience isn’t enough to get you a job, but that’s kind of how it works.”

Young coaches and graduates can also run into roadblocks because of the lack of money provided for graduate assistant jobs. NCAA rules mandate that an “individual may not receive compensation or remuneration in excess of the value of a full grant-in-aid for a full-time student.”

While there is a wide range of graduate assistant salaries, the average pay is $7,500 and most colleges don’t offer health insurance.

Hardy said those who want to immediately become coaches tend to take entry-level, low-paying jobs, but he didn’t have that luxury because of his financial situation. After Hardy finished his four years of college basketball for the Wildcats, he played professionally in Finland for a season and then looked for a well-paying job.

“I couldn’t have called my mom and said, ‘Can you pay my rent for the next 10 months while I chase this dream of becoming a college basketball coach?’” he said. “That wasn’t going to happen.”

Instead of going down a low-paying route, Hardy starting working at J.P. Morgan. Around the same time Hardy accepted the position, Big Ten commissioner Jim Delany was looking for a coach on his son’s AAU team and asked him to fill the position.

But what he didn’t realize was that “side job” would eventually spark a passion for coaching.

Through the AAU system, Hardy eventually took a job under Carmody. Despite not following a typical route to become a coach, Hardy was still able to quickly climb the ranks.

The NCAA has recently come up with a new rule change that went into effect April 1, reducing access to view AAU events in July from three weekends to one. While this would affect the number of players Hardy and his staff can scout, it also impacts the number of coaches he can evaluate. Without access to AAU events, personnel looking to fill their staffs aren’t able to see potential coaches in action.

Hardy said the AAU track isn’t a traditional one, and young black coaches — a position he was in more than 10 years ago — are going to get left behind.

“As a head coach, I want to see guys in an element that’s similar to what we do on a day-to-day basis,” Hardy said. “To be able to watch guys at the grassroots level coach their teams is important to me, and, with the new NCAA rules, we’re going to lose that opportunity.”

Getting the big break

Despite barriers preventing access to head coaching jobs, there are a high number of black assistant coaches across the country.

Across Division I in 2018, there were 599 black assistant football coaches, along with 464 black assistant men’s basketball coaches and 413 black assistant women’s basketball coaches.

Hardy said he doesn’t believe there’s a lack of diversity when it comes to assistants but definitely sees a disparity when it comes to head coaches. In each of the three sports, data shows the pipeline for black coaches shrinks disproportionately compared to that of white coaches.

“If you look at the coaching carousel this season, the number of black assistants that are getting jobs is down from last year,” he said, “especially in relation to the number of black coaches that… resigned or (were) let go.”

In football, the most desirable assistant coaching positions are offensive and defensive coordinator, positions that were filled by 24 and 45 black coaches respectively last season, compared to 428 white offensive and defensive coordinators.

The majority of prospective head coaches are chosen from defensive, offensive or special teams coordinators spots, like Green was in 1980.

Former Northwestern women’s basketball coach Tiffany Coppage. Coppage coached for the Wildcats for two years before leaving for the University of Alabama.

When it comes to women’s basketball at Northwestern, there has been turnover on the coaching staff over the past few seasons. The program has had five black assistants in the past five years.

Assistant coach Tangela Smith, who just finished her first season with the women’s basketball team, is Northwestern’s sole black female coach and declined to be interviewed for the story.

None of the other four coaches stayed with the program for more than five years — with two taking head coaching jobs and two moving on to assistant coaching jobs elsewhere. Pointer and Nebraska Wesleyan head coach Sam Dixon are now leading programs.

Pointer said it often takes women of color longer to get head coaching jobs, a process that starts in administrative positions in the NCAA and has a trickle down effect. She cited St. Francis (PA) head coach Keila Whittington who worked in various lower-level positions for 39 years before getting a chance to lead a team.

“It should never take that long,” Pointer said. “Sometimes that happens with us women of color, we always are in a position where we know that it may take longer, but you can’t give up on your journey.”

Banks, along with Hardy and Pointer, acknowledged that black coaches also don’t get second chances as often as other coaches.

“That second chance is even harder to come by if you’re not successful at your first stop,” Banks said. “There are a lot of qualified black females in our profession and I would love to see us get more opportunities.”

Staying within your comfort zone

Ultimately, the decision-makers when it comes to who gets hired and who gets second chances are athletic directors and others in higher administrative positions. Lapchick believes athletic directors are leaders on their campuses and having diverse opinions will allow for more representation of racial minorities.

But the lack of diversity isn’t limited to coaching, and it extends into the highest levels of athletic departments.

Last season, 84.3 percent of all Division I athletics directors were white, according to TIDES’ 2018 Racial and Gender Report Card. In terms of gender diversity, the percentage of female athletic directors decreased from 11.2 percent to 10.5 percent from 2017 to 2018.

Hardy said he thinks athletic directors hire who they feel comfortable with, which leads to an undiverse coaching pool. Banks believes that the lack of gender diversity among athletic directors specifically leads to fewer female coaches in women’s basketball.

“I’m a strong advocate of having different voices in the room because I think that they are valuable,” Banks said. “I would like to see more females in coaching, I would like to see more females in administration in all those athletic director roles.”

In football, Hinton said Green’s hiring at Northwestern opened more doors for black applicants. Ayeni believes by putting people of color in close proximity to decision-makers like athletic directors, those coaches get more exposure.

“A lot of these guys don’t want to hire people they don’t know (because) there’s too much at stake,” Ayeni said. “The more (black coaches) can be around people who are in the position to make the decisions, the better.”

NU has taken some progressive steps toward fixing the imbalance — Phillips was honored by the NCAA Minority Opportunities and Interests Committee as a Champion of Diversity and Inclusion.

During his tenure, Phillips created a senior staff position focused on improving diversity and inclusion within Northwestern athletics, which is held by Maria Sanchez. Of the athletic department’s executive staff, 60 percent are women or people of color — in addition to about half of the department’s senior staff.

To improve diversity among coach staffs, Hardy said athletic directors and presidents need to establish authentic relationships with coaches they don’t typically see. Hardy — along with Ayeni and Baldwin — said Phillips does a great job of establishing relationships with his staff, even assistant coaches.

Phillips said earlier this year in an NCAA article that creating a diverse pool is a priority of his, even if it means extra work on his end.

“That may mean making some additional phone calls,” he said. “That may mean working a little bit harder to find those candidates. If you think you’re going to find the right person by just letting people apply for the opening, then you’re mistaken. You have to actively recruit and educate yourself on the market and who’s out there.”

Gaining exposure

While Phillips has made a concerted effort to improve diversity at Northwestern, some hope more structural changes take place in Evanston and across the country.

Similar to official guidelines like the NFL’s Rooney Rule, which requires that every NFL team interviews one minority candidate for head coaching and general manager positions, Lapchick has been a public proponent of incorporating similar bylaws like the “Eddie Robinson Rule” and the “Judy Sweet Rule” into college hiring.

“Both are designed to improve and diversify the racial and gender hiring practices in college sports,” Lapchick said. “Incorporating these rules would put the NCAA at the forefront of diversity and inclusion.”

This could be an effective method to improve diversity; however, while the Rooney Rule has brought in black coaches, it hasn’t helped to keep them around long term, as there are currently only two in the NFL.

While small steps have been made to improve representation in some areas, Pointer said it can be hard to determine what marginalized identity is causing the root of the problem.

“There are challenges in terms of black women are not as represented from a head coaching statistical standpoint for NCAA women’s basketball,” Pointer said. “However, there are challenges for everyone. It’s hard to decipher what’s the difference between: What’s difficult for someone else or is it difficult because of being an African American woman.”

The NCAA is working on mentorship programs that create more opportunities for minority coaches to get exposure.

Ayeni had the opportunity to participate in the Bill Walsh Diversity Coaching Fellowship, which allowed him to make connections in the industry. Through this program, Ayeni met former Bears’ head coaches Lovie Smith and Marc Trestman.

The program allows coaches to gain experience by shadowing other coaches, learning more about the NFL system and receiving tips on how to improve their coaching.

“It’s a chance to get yourself in front of a bunch of coaches who not only are good teachers and you can learn some good stuff,” Ayeni said. “But they get to see you work and see you coach and see if there’s anything that you can do to help them or they can do to help you.”

1991 Northwestern men’s basketball team. Pat Baldwin (standing, far left) coached at 5 different schools before getting a head coaching job at Milwaukee.

Ayeni will have more opportunities to gain exposure as he will head to the NCAA Champion Forum for Football in June.

This forum brings together coaches of color from the NCAA “with a focus on providing tailored education to talented rising stars who will lead the next generation of college head coaches.” Along with the minority coaches, athletic directors, conference executives and university presidents also participate in these events.

Many of the networking possibilities currently presented to Ayeni would not have been available to other black coaches like Cooks or even Green. However, being a black head coach in the NCAA is still not seen as a norm, despite the percentage of black assistant coaches that exist in the college athletics.

Unlike the majority of black coaches, Baldwin, Hardy and Pointer have ascended the coaching ranks to become leaders of their respective teams.

As Baldwin continues to live out his dream as head coach at Milwaukee, he believes he has a responsibility to be a role model and represent himself and his family.

But when Baldwin looks back on his career, he doesn’t want to be seen a black coach — he wants to be seen as the best coach. The Northwestern alumnus believes that as long as coaches have a love for the profession, it shouldn’t matter what race they are.

“When it comes to diversity, if you have a passion for this and you love it and you truly care about the student-athlete experience and what it really means to be a coach, it doesn’t matter if you’re a minority or non-minority,” Baldwin said. “There are some really good people that recognize that and they’ll find you.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @andrewcgolden