In Focus: Years after surgery, new documents renew patients’ malpractice claims against Northwestern Memorial doctor

May 23, 2019

Thirteen years ago, Northwestern Memorial Hospital’s renowned cardiac surgeon Patrick M. McCarthy began operating on his patients’ hearts using a new invention.

McCarthy designed the Myxo-ETlogix 5100 annuloplasty ring, devised to treat the most common form of heart disease, called “myxomatous mitral valve disease.”

The mitral valve regulates blood flow from one chamber of the heart to another. The disease is characterized by lengthened or thickened leaflets that prevent the mitral valve from opening and closing smoothly. If left untreated, small amounts of blood can leak backward into the valve as the heart pumps, which could lead to complications like a heart murmur, stroke or death. An annuloplasty ring reinforces and repairs the heart valve.

McCarthy’s annuloplasty ring was designed to improve his patients’ health, but just years later, his invention was in deep water — it had faced a U.S. Food and Drug Administration rebuke and several lawsuits from patients alleging the surgeon performed human trials for the ring without their consent. It has also been subject to investigations by the FDA and U.S. Senate, both of which ultimately fizzled out.

Former patients and their families said what they thought was a straightforward, one-time operation led to years of heart problems. They’ve been waiting for a legal response in their favor for over a decade.

Now, former patient Maureen Obermeier is trying her hand again.

In February, Obermeier filed a petition to overturn the dismissal of her 2008 lawsuit, which alleged poor medical treatment by McCarthy. The petition is based on new information revealed through a Freedom of Information Act request showing that, at the time of her 2006 surgery, McCarthy’s annuloplasty ring was not FDA-approved and the surgeon was not given permission from Northwestern’s Institutional Review Board to operate with it.

The lawsuit names McCarthy, Northwestern Memorial, Edwards Lifesciences and Northwestern Medical Group — formerly known as Northwestern Medical Faculty Foundation — as defendants.

“This started in 2006,” Obermeier said. “Now it’s 2019, and we’re still fighting the same fight.”

Regulatory loopholes

During the initial stages of the ring’s development, its manufacturer, Edwards Lifesciences, benefited from a FDA regulatory loophole that allowed it to skip the stringent review process typically required for a potentially life-threatening device like an annuloplasty ring.

The FDA categorizes medical devices into three groups based on increasing risk to patients: Class I, II and III. Devices classified under Class III “support or sustain human life, are of substantial importance in preventing impairment of human health, or which present a potential, unreasonable risk of illness or injury,” according to the FDA. Common Class III devices include implantable pacemakers and breast implants. The FDA requires Class III devices to undergo the more rigorous “premarket approval,” which is the only route that requires clinical testing.

But in 2001, the Advanced Medical Technology Association successfully petitioned to lower annuloplasty rings from Class III to Class II. The reclassification allowed McCarthy’s invention to bypass “premarket approval” and go through a less rigorous process for FDA approval.

When a device is similar enough to another previously FDA-approved model, the manufacturer can claim “substantial equivalence” to forgo federal regulatory processes altogether.

Edwards Lifesciences — for which McCarthy works as a consultant — said his invention was similar enough to other annuloplasty rings, despite claiming 40 unique characteristics on its patent application to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Companies like Edwards Lifesciences have received intense backlash from medical professionals for using the loophole. They say similar models do not guarantee the same safety or effectiveness.

McCarthy and Edwards Lifesciences did not respond to requests for comment.

After multiple patient allegations that the ring implant they had received had not undergone FDA approval, a U.S. Senate investigation prompted a FDA rebuke that required the ring to be submitted for Class II approval. The FDA disagreed with the manufacturer’s original claim that the new ring was similar enough to past devices.

The application for FDA clearance was submitted in 2008 and in April 2009, the ring had been cleared under a different name: the dETlogix annuloplasty ring 5100.

By that time, McCarthy was already three years into patient trials.

Pending lawsuit

One of those patients was Obermeier, who received the ring implant during her 2006 mitral valve repair at Northwestern Memorial. She called her surgery “the worst experience” of her life.

“I felt so sick post-surgery, I could barely get out of bed,” she said.

Northwestern Memorial also could not offer her an explanation, she said, and she begged to be released because she felt so ill.

When her new cardiologist at the Advocate Christ Medical Center in Oak Lawn, Illinois, asked her about the surgery, Obermeier said she wasn’t aware of any complications. The only way she was able to find out was by requesting her medical records from Northwestern Memorial.

After reviewing her hospitalization charts from 2006, the cardiologist found elevated troponin values and concluded she suffered a heart attack during her surgery and multiple episodes of cardiac arrest within 24 hours of the operation, Obermeier said.

Obermeier said McCarthy assured her that her surgery went smoothly, she received no medical follow-up and was administered no treatment for her heart attack.

“He had nothing to say about what happened during the surgery,” Obermeier said of McCarthy. “So it was like I got lied to.”

McCarthy later confirmed the heart attack in a 2011 court hearing and 2012 legal deposition.

After the surgery, Obermeier said she experienced multiple episodes of arrhythmia, or irregular heartbeat. When she asked doctors at Advocate Christ to see if corrective surgery was possible, she said they told her the severity of her heart attack damaged the organ too greatly for additional operations.

Obermeier believes the experimental ring implantation and her untreated heart attack contributed to her poor health post-surgery.

“I didn’t have any answers until I had to file a lawsuit,” Obermeier said. “It’s scary that you have to take your attorney with you just to get a surgery.”

Once she learned what happened during the procedure, Obermeier sued McCarthy, Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Northwestern Medical Group in 2008. She alleged a failure to adequately assess her cardiac status, as well as harm, damage and traumatization to one or more of her coronary arteries.

Still, an Illinois state court jury ruled in favor of McCarthy and Northwestern Memorial-affiliated defendants in April 2016, clearing him of allegations for negligence and operating without informed consent.

Obermeier’s current lawsuit is based on a 2018 FOIA request filed by Nalini Rajamannan, a cardiologist who formerly worked on McCarthy’s surgical team at Northwestern Memorial.

Obermeier believes the FOIA documents contain evidence proving McCarthy guilty of performing experiments without patient consent and were kept secret by McCarthy and Northwestern Memorial.

A FOIA to find more

With her FOIA request, Rajamannan uncovered documents that she and former patients believe are key to a verdict in their favor.

Rajamannan, a former associate professor at Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine, said she grew concerned with McCarthy’s surgical practices after multiple patients, including Obermeier, came to her post-operation and said their health problems were ignored by McCarthy.

That led to her challenging the ethics of McCarthy’s surgeries. She was denied tenure and discharged from Northwestern, and in the time since, Rajamannan has worked with past patients to seek legal action against the renowned Feinberg surgeon.

According to documents from her FOIA, the Northwestern Institutional Review Board — a group responsible for protecting the rights and welfare of human subjects involved in research at Northwestern — authorized McCarthy’s research on the ring in 2006. Its understanding, documents show, was that his studies would be retrospective.

That meant McCarthy was only authorized to review past medical records of patients who had undergone mitral valve repair between April 2004 and June 2006. He was not granted permission to operate with the Myxo ring.

However, The Daily obtained a 2005 Edwards Lifesciences document from Rajamannan that recorded McCarthy’s input on the design of the ring at the initial stages of the device’s development. The document said McCarthy intended to operate on at least 10 patients with the prototype.

“Dr. McCarthy indicated that if the first 10 implants went well, he would feel comfortable expanding the use of the device to other surgeons,” the document stated.

These operations were carried out without IRB approval and took place before McCarthy’s IRB request to review past patient records.

When McCarthy filed a new request to expand his review into 2007 records, the board determined his research was no longer retrospective and requested for additional information. Instead of submitting details about his research to the IRB, he decided to terminate it altogether.

In 2007 emails obtained by The Daily, a representative from McCarthy’s team confirmed to the IRB that the research project would be closed.

“After further consideration, we have decided to terminate this project,” the email said. The email also confirms that no research has been done since McCarthy’s approval for retrospective reviews expired on June 27, 2007.

However, his 2008 publication in The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery — titled “Initial clinical experience with Myxo-ETlogix mitral valve repair ring” — stated that “100 patients received the Myxo ring, which is a Food and Drug Administration-approved ring.”

He had not been given permission to operate at the time, and the Myxo ring was not cleared by the FDA until 2009.

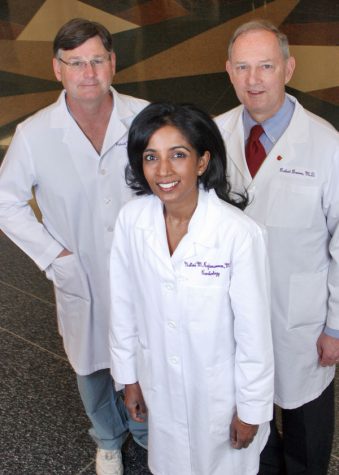

Patrick M. McCarthy, Nalini Rajamannan, and Robert Bonow on the front cover of a 2007 Northwestern Memorial Hospital cardiovascular review. Rajamannan, who used to work with McCarthy, filed a FOIA in 2018 that Obermeier is using in her new lawsuit.

Obermeier believes she was one of the patients whom McCarthy operated on after the IRB’s expiration date.

Bringing it back to court

In light of the newly discovered findings, Obermeier filed her current suit, alleging that the defendants “concealed” information during the 2008 trial.

Obermeier alleges her surgery proceeded without informed consent — and after McCarthy told the IRB he’d stop the research after its request for additional information. The IRB project Obermeier cited in her petition was the medical record review between April 2004 and June 2006 — but she was operated on in November later that year.

In a March response, the defendants denied multiple claims Obermeier makes in the ongoing suit, saying, they failed to see the connection between the evidence cited and Obermeier’s case due to gaps in the timeline.

The defendants didn’t address Obermeier’s claim that she didn’t consent to McCarthy’s human trials beyond the IRB-approved window of retrospective chart reviews.

Instead, they argued Obermeier has no claim to a suit because she had no involvement in the 2004 to 2006 study she cited as evidence — and signed a consent form to take part in a record of patient surgery outcomes.

Northwestern-affiliated defendants cited Obermeier’s signature as evidence for informed consent, but Obermeier said she wasn’t consenting to be implanted with an investigational device.

Obermeier said she knew she was going to receive an annuloplasty ring, but McCarthy never mentioned he invented the ring or that the ring had not undergone any federal approval processes. The ring implant Obermeier received was called the “McCarthy Annuloplasty Ring” on her device identifier card — it was the preclinical, rudimentary version of the model that was later submitted for FDA clearance.

“There were many rings on the market at that time that had been used for years,” Obermeier said. “I would never have agreed to what he did to me.”

In the defendants’ response, McCarthy maintained he used his invention during Obermeier’s surgery because “he felt that it was the best device to address her problems.”

The defendants have the right to file a second motion within the next two weeks, and Obermeier will have the right to file a response. Both sides will present arguments in an appellate court on June 13.

Obermeier hasn’t been alone in filing legal challenges.

Former patient Antonitsa Vlahoulis, who claimed she was unaware until well after her 2006 operation that she was implanted with an experimental ring without her consent, sued in 2008.

The lawsuit was ultimately dropped due to mounting legal fees. Vlahoulis filed a second suit that was dismissed before it went to court.

A former patient’s death

Along with Obermeier’s ongoing suit, the recent death of one of McCarthy’s former patients drew even more attention to his alleged wrongdoings.

Lynne Knotts kisses her husband William Knotts on the forehead after his corrective surgery. Doctors at Advocate Christ Medical Center said a corrective surgery was needed after William Knott’s 2014 procedure with McCarthy.

William Knotts received mitral valve repair surgery with McCarthy in 2014. He died of a stroke four years later on Nov. 22, 2018.

His son, Steven Knotts, remembers his father before the surgery as one of the healthiest people he knew. William Knotts was an active man who, in his 70s, was still able to go on skiing trips every year in Colorado with his wife, his son said.

But after the surgery, Steven Knotts said he watched his father grow progressively weaker and face new health problems, like lightheadedness and chronic low blood pressure.

When his father reported his health problems to McCarthy after the operation, Steven Knotts said McCarthy assigned him a psychiatrist instead of running tests to determine the cause of his discomfort, suggesting his health complications were “all in his head.”

The Knotts did not believe McCarthy’s explanation, and with William Knotts’ condition worsening, his son and wife, Lynne Knotts, felt they had no other choice but to try another hospital that might give them the answers they needed.

After performing heart examinations at Advocate Christ Medical Center, his cardiologist there found that William Knott’s mitral valve leaflet — a part of the heart valve that, when functioning healthily, should be able to open and close freely — had been “crudely” stitched closed.

McCarthy “thinks he can do whatever he wants and get away with it,” Steven Knotts said.

William Knotts was told he needed corrective surgery because of the stitching of the leaflet and received the second operation at Advocate Christ in June 2018. Consecutive surgeries weakened his heart before his death.

Knotts filed a Northwestern EthicsPoint complaint reporting suspected ethical misconduct on behalf of his father in October. But Jay Walsh, Northwestern’s vice president for research whose office oversees the IRB, said he said the University never received the complaint, according to a 2018 email obtained by The Daily.

Lynne Knotts said she had asked for a face-to-face meeting with Walsh earlier this year, but her request was never granted.

Walsh forwarded The Daily’s comment request to a University spokesman, who declined to speak.

However, when he was presented with the released FOIA documents, Walsh said in a email last year to the Knotts family that “there were no research interventions, device testing, or experimental surgeries done as part of either of those studies.”

Finding a way forward

For Obermeier, the Knotts family and other patients who say they’ve been hurt by McCarthy’s alleged human trials, the FOIA documents represent not only a legal pathway to requesting another trial, but renewed hope that something consequential will finally come out of the years-long fight.

“Everybody keeps protecting him, circling the wagon,” Obermeier said. “With this new evidence, it will be much clearer what wrongs were done to me and the other patients.”

Steven Knotts said he hopes McCarthy will receive some form of reprimand to make sure nobody else is hurt in the future.

“The rules are black and white, and the violations are black and white,” Knotts said.

The outcome of the new lawsuit is still to be determined, but Obermeier said she is hopeful that the FOIA documents are a turning point that will finally “end the cycle of horrible behavior.”

But even if the lawsuit is settled in her favor, Obermeier has to deal with the ramifications of her 2006 surgery for the rest of her life. She will continue to rely on a number of medications and have to live a restricted lifestyle.

“My life is completely different now,” Obermeier said. “My cardiologist told me, ‘You’re alive probably only because you’ve worked so hard at staying alive.’”

Email: amyli2021@u.northwestern.edu