Protest to performance: Amazingrace Coffeehouse’s place in Northwestern history

March 6, 2019

Just over 40 years ago, there was a little bit of magic on Northwestern’s campus.

Born during the Vietnam War protests in 1970 and forged in Scott Hall and Shanley Pavilion, Amazingrace Coffeehouse quickly became the stuff of legend. One part food hall, one part music venue, one part counterculture collective, it remains singular in the University’s history.

“There were many, many shows that we would walk away from going, ‘We got magic tonight,’” said Benj Kanters (Communication ’75, Bienen ’02). “Magic happened.”

But before there could be magic, there was a war.

In the spring of 1970, a student strike erupted in protest of the shooting at Kent State University, which had been embroiled in its own protests of the U.S. invasion of Cambodia during the Vietnam War. It was a time to make statements, said founding member Jeff Beamsley (McCormick ’72), and students did so in large numbers. Northwestern students stopped going to classes and became vocal in protesting the war.

Student protesters took down campus fences and erected a barricade on a south campus stretch of Sheridan Road — it stayed up for about a week and blocked traffic — which required constant supervision lest it be dismantled by police.

“We not only are not going to go to school anymore, but we have to do something to indicate to the rest of the world that we believe that something needs to change,” Beamsley said.

And every revolutionary cause needs a little bit of fuel.

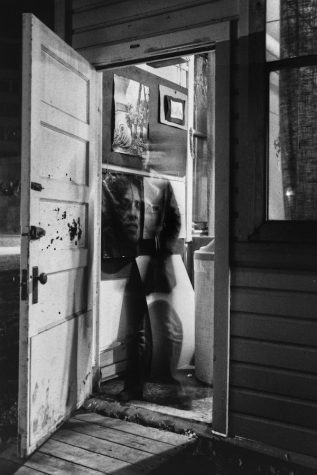

The door to Shanley Hall.

Amazingrace formed “out of necessity,” Beamsley said. A group of students ended up “liberating” a basement kitchen in Scott Hall that was closed in anticipation of the Norris University Center opening. They received food donations and cooked meals for the protesters.

Thus, the Scott Hall Grill Committee was born.

The protests might’ve stopped after that spring, but the students in Scott Hall remained, with a plan to keep serving food and expand their concept. They came from various schools and majors — there were engineers, film students and everyone in between — and pooled their talents, helping out wherever was needed.

The University recognized the committee as an official student organization and helped the group transform the Scott Hall kitchen into a venue that accommodated student performers. They began inviting live musicians to play sets, and not long after, the coffeehouse filled up night after night.

After a local act closed out their set with a rendition of “Amazing Grace,” it quickly became tradition, said Darcie Sanders (Weinberg ’79). Eventually, the venue’s founders — affectionately dubbed ‘Gracers — painted the song’s name on the wall by the serving area in Scott Hall and dropped the second ‘G.’

The name stuck, and Amazingrace was born.

How sweet the sound

As the group formalized, members bought a house on Colfax Street where they could all live together. Then, in 1972, after NU determined the group needed to vacate Scott Hall — which was slated to become office space — they moved across campus into Shanley Pavilion.

The Shanley years were formative and allowed the group to cultivate their own sound and reputation as a music venue. They weren’t trying to create a bar, but an all-ages space for food and music.

Margot Myers (Communication ‘75), another member of the group, said she first started out in Amazingrace’s kitchen in the summer of 1973. She started working in the Shanley kitchen, cooking lunches and dinners throughout the week.

The ‘Gracers worked in shifts and were known for their big-batch meals, granola and fresh bread — healthy fare with lots of vegetables that could be served cafeteria-style.

Meyers said the menu changed depending on what they were able to get delivered and that often, they would make up names for the dishes. If a recipe didn’t turn out quite as planned, there was a funny name to hide the mistake.

Amazingrace in Shanley was a cozy affair. The building held about 240 and was outfitted with a commercial kitchen and serving counter. A stage to the left and a set of turntables rounded out the space.

Seating was limited, so most guests occupied the concrete floor.

In the spring and summer months, when shows would sell out or there were multiple performances in one night, the ‘Gracers opened the windows and set up loudspeakers so the sound could travel outside.

There was something special about attending a concert at Amazingrace: there were close to no barriers between the audience and musicians. According to Beamsley, “the performance didn’t stop at the walls of the structure.”

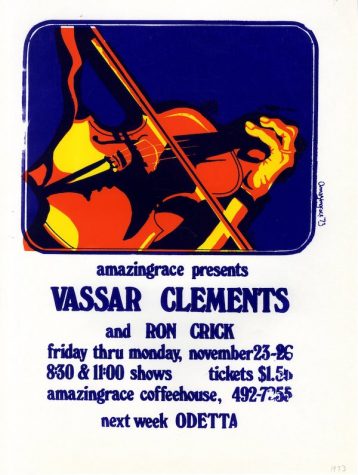

A poster advertising a Vassar Clements concert.

He recalled one performer who asked audience members to hold hands during a portion of a set. The loudspeakers were on that night, and when he looked outside, he could see that people had formed a circle all around Shanley. They, too, were holding hands.

To Beamsley, it was pure magic.

“That was really the drug that we were all addicted to,” he said. “The audience might experience it once, or if they came often, maybe several times. But they didn’t realize that was our experience every night, two shows a night every night.”

Sound was crucial to the ‘Gracers. They were able to record the Shanley concerts and create a technical quality that was appreciated by performers and audience members alike.

“We were doing things technically that nobody considered doing in a nightclub environment,” Kanters said. “It was like sitting in a giant living room with a big stereo system. … The musicians kind of looked at it as musicians’ club and the audience within it as a listening club, and so everybody came pretty happy.”

Grateful Dead or nothing, f—k your other ‘big name groups’

In 1973, the ‘Gracers teamed up with Chicago-based Jam Productions to book a major act for the homecoming concert. Though the Grateful Dead agreed, the University was more apprehensive; it wasn’t until a group of students protested at the Rebecca Crown Center that the administration was swayed.

The concert was scheduled for McGaw Hall, which now houses Welsh-Ryan Arena. Back then, the building was a wide open space and not known for its acoustics. Andy Frances (Communication ’71) recalled that the band’s location scout — known only as “The Kid” — came to look at the space and wasn’t particularly impressed.

To try to better the acoustics, the ‘Gracers bought reams of parachute fabric, which they hung from the rafters using a rented cherry picker. They remember having to dunk the fabric in flame retardant after being reprimanded by the Evanston fire marshal. Pressed for time, the parachutes couldn’t be left to dry and they scrambled to re-hang them while they were still sopping wet.

“The fiberglass bucket (on the cherry picker) started to split because of the weight from the parachutes,” Beamsley recalled, “and every time we took another one up the split got bigger.”

In retrospect, Kanters admits, the parachutes didn’t do much for the acoustics after all. But the band brought along an enormous construction of speakers and PA systems — which were the precursor to their infamous “wall of sound.”

The interior of McGaw Hall during the Grateful Dead’s concert at Northwestern.

The concert, for all intents and purposes, was a hit.

The preparation and setup “nearly killed” them, Beamsley said, and the night was amazing, but it wasn’t quite the same feeling the ‘Gracers were able to produce in their own space.

“It was … another one of these accomplishments of a small group of people who loved and trusted each other, and were willing to do whatever it took to get things done and didn’t care about the rules,” Beamsley said.

Becoming Northwestern history

As Amazingrace grew in popularity and became a bona fide music venue, the ‘Gracers started graduating. Pretty soon, only two of them were still enrolled as students.

This put into question the group’s status as a student organization. At the same time, Evanston’s brothel law pressured the ‘Gracers to vacate their house on Colfax Street. The situation came to a head and the group’s Shanley haven soon dissolved.

One group of ‘Gracers stayed in Evanston, founding Amazingrace at Main Street and Chicago Avenue, while another went to Eugene, Oregon to continue living and working in a collective. Both groups eventually fizzled out, and by 1980, Amazingrace was a part of history.

Still, the ‘Gracers remain friends — some have even married each other — and they count their time with the group as formative in their lives.

“I can liken it in a certain way to teenagers putting together a band,” said Flawn Williams (Communication ’74). “Only in this case, it was a band of producers, a band of very highly artistic and energetic and politically focused people.”

Bill Graessle said he felt something special the moment he stepped foot in Amazingrace.

“I immediately became friends with them,” he said. “It was like I had been waiting my whole life to meet my real family.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @kristinakarisch