Men’s Basketball: Winter’s reign at NU remembered for upsets, terrific coaching

October 30, 2018

As the buzzer rang at the end of the second half on Dec. 1, 1975, at McGaw Hall, Northwestern fans inside the arena exploded in excitement and flooded the floor.

The Wildcats had just upset the defending NCAA Tournament runners-up and No. 6 Kentucky, 89-77, in the visitors’ first game of the season. One year earlier, Kentucky had blown out NU in the Bluegrass State by 27. But this time around, NU was the team holding a 20-point lead in the second half and celebrating the victory.

On the sidelines, leading the Cats to one of the greatest victories in program history, was coach Tex Winter.

Winter — who died three weeks ago at the age of 96 — spent five seasons at the helm of the NU basketball program from 1973 to 1978 and finished with a losing record. But his time in Evanston was only a blip on an otherwise impressive resume.

About seven years after leaving the shores of Lake Michigan, Winter returned to Chicagoland to take an assistant coach job with the Chicago Bulls. When Phil Jackson was hired as the head coach in 1989, Winter convinced him to utilize the triangle offense, also called the triple-post offense. Jackson agreed, and eight years later, Jackson, Michael Jordan, Scottie Pippen and Winter had six NBA titles to their names.

Then, when Jackson moved on to the Shaq-and-Kobe Lakers of the early 2000s, Winter went along with him, teaching his beloved offense to the two all-time greats. By the time Winter retired and was elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2011, he had NBA Championship rings for all 10 of his fingers — with one left over.

“Tex gave us a way to play the game of basketball that was principled,” Jackson said at Winter’s memorial ceremony on Oct. 20. “We talked about playing according to the basketball gods. He lived that life. And we’re thankful for it.”

But, before all of that, Winter made his mark on the college game.

Hiring Tex

When former Cats’ coach Brad Snyder resigned at the end of the 1972-73 season, Winter was already a well-renowned coach.

Hired at the age of 29 by Marquette, Winter spent two seasons with the Golden Eagles before moving on to coach Kansas State. He had his best collegiate seasons in Manhattan, Kansas, spending 15 seasons with the program and leading them to two Final Fours and a No. 1 ranking during the 1958-59 campaign. He then spent three years at the helm of Washington before leading the Houston Rockets for one-and-a-half years.

By the spring of 1973, Winter was no longer with the Rockets and was looking for a new job. Northwestern Athletic Director Tippy Dye was interested. On Snyder’s staff was former NU player Rich Falk, who recalls talking with Dye at the time about the vacancy. Dye told Falk he wanted a proven head coach and that Winter was one of the best options available.

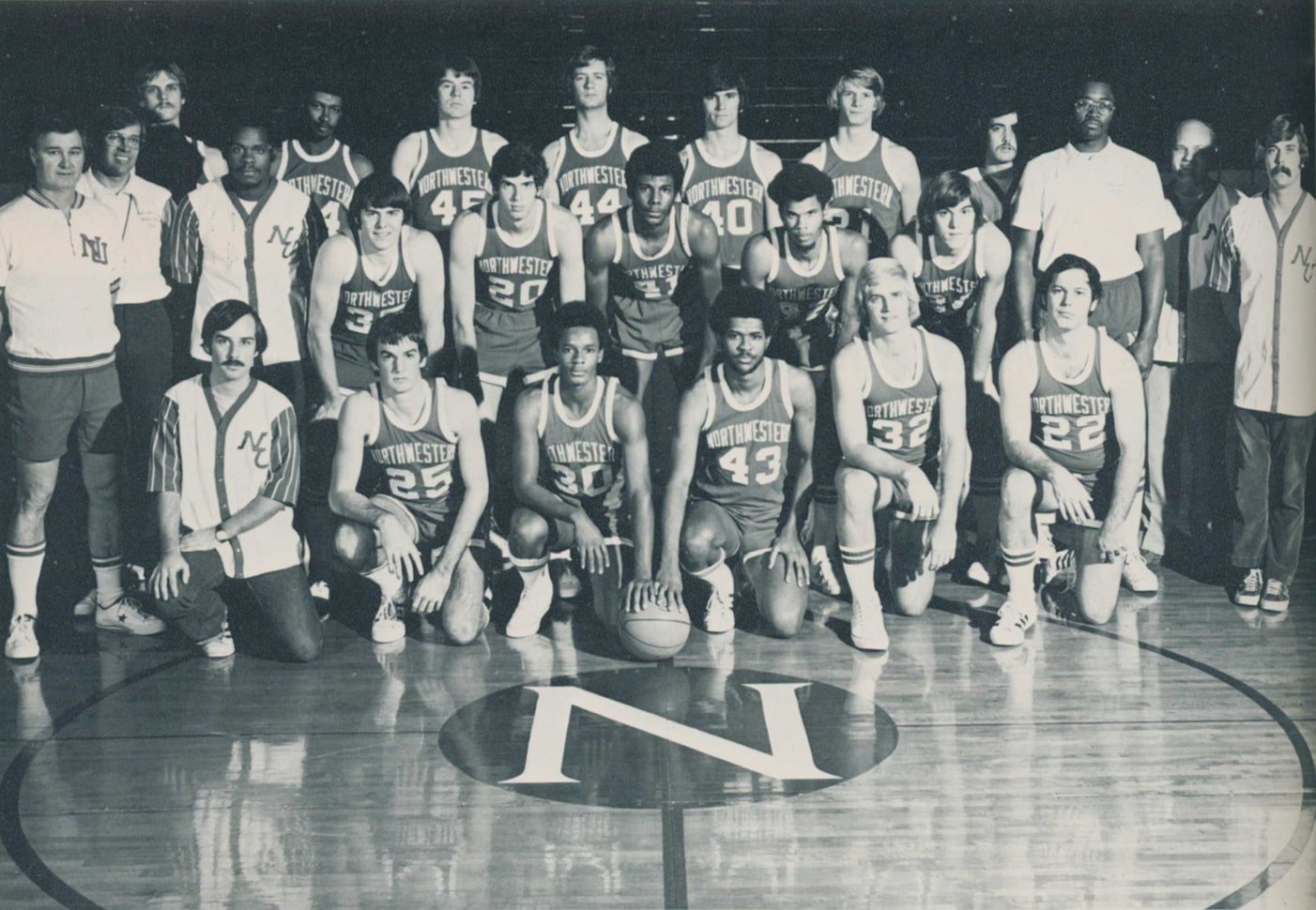

The 1974-75 Northwestern team poses for a team photo. The team finished the season with a 6-20 record.

Winter was hired on April 4, 1973. One of his first moves was to keep Falk and Dan Davis, Snyder’s other assistant, on his staff.

“I’m looking forward to coming back to college ball,” Winter told The Daily at the time. “I feel that I’m a teacher type of coach, and you have the opportunity to teach more in college.”

Teaching and Practice

While Winter is remembered as the pioneer of the triangle offense, he is not the father of the offense. That honor goes to Basketball Hall of Fame coach Sam Barry, who coached Winter at Southern California for a season in the 1940s. But no single person in the history of basketball is as synonymous with the offense as Winter. He published “The Triple-Post Offense” in 1962, the de facto book on the offense. He ran the offense everywhere he went and was its biggest proponent.

Yet, he also made waves in other aspects of basketball. He created the toss back — a machine that allows players to practice passing by themselves. So when Winter stepped foot in McGaw Hall — now known as Welsh-Ryan Arena — for the first time, his brilliance was well known around the basketball world.

John Caccese, who spent four seasons as a student manager from 1974-1978, remembers one day when George Raveling visited practice. At the time, Raveling was the leader of the Washington State program, and would later became the head coach of Iowa and USC before being elected to the Hall of Fame.

When Raveling was leaving, Winter told Caccese to drive the coach of the Cougars to his car.

“As I’m driving him, I asked him what brought him to Northwestern,” Caccese said. “He goes, ‘Well Tex Winter is the greatest teacher in college basketball. He gave a seminar, and it was three hours, on footwork, to other college coaches. Three hours on footwork. I’ve never experienced anything like it. I never knew I could learn so much.’”

Bob Svete, a forward who played three seasons for Winter’s Wildcats, said Jerry Krause, who was an NBA scout during the 1970s and would go on to serve as the general manager of the Chicago Bulls during the Jordan era, would also attend practices.

Those practices, which were based around the fundamentals and preparation, featured many recurring themes. Players would jump rope before every practice, work on guard-forward entry passes and break down the triangle offense on both sides of the floor.

Svete said Winter was “a tremendous X-and-O guy” and he did not need to yell or scream to get across his ideas.

“He didn’t have to throw a chair or kick anything over to make a point,” Svete said. “He would look you straight in the eye and let you know if you were living up to his expectations and if you weren’t, what he wanted more from.”

Billy McKinney, a 6-foot guard who played from 1973-77 and was one of the best players in program history, said Winter never sugar-coated anything and was “detail-oriented.”

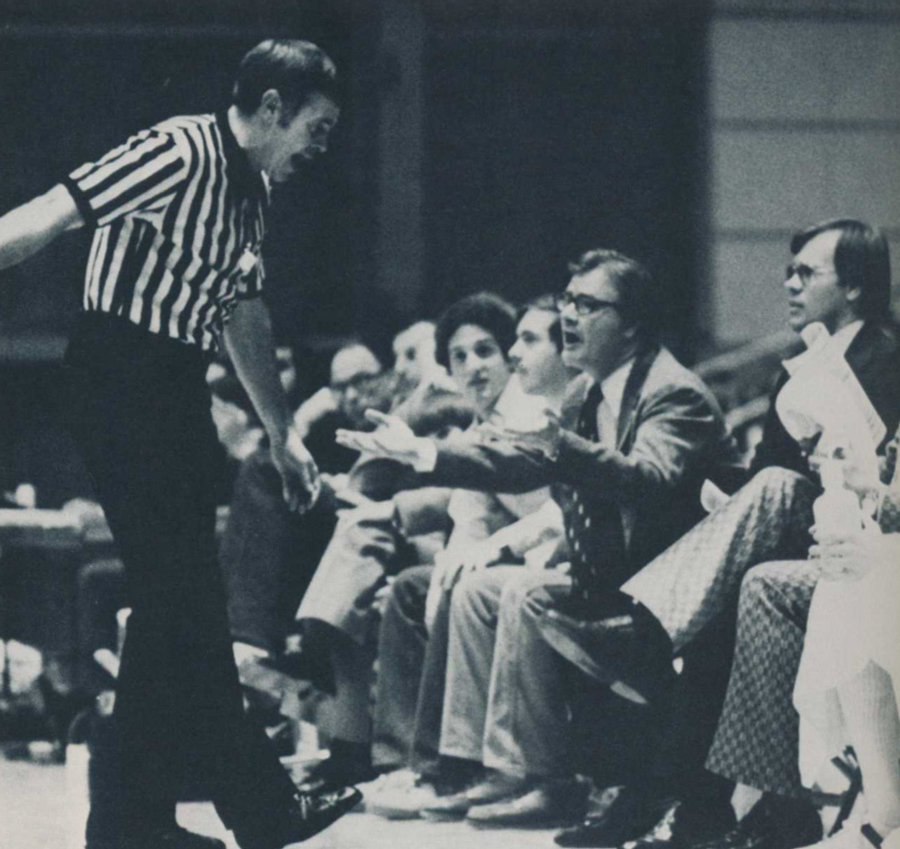

Tex Winter discusses a call with a referee during the 1977-78 season. Winter won 42 games at Northwestern.

Under Winter, the Cats began to videotape practice and games, which was an uncommon sight in the Big Ten at the time. Winter had been videotaping since he first became a head coach and would sometimes use old video to show his players how the offense should be run.

But Winter did not only use video make a point. Sometimes, he got on the court himself.

“He was a terrific teacher and a terrific demonstrator that left no detail unterned in terms of preparation,” McKinney said.

Falk, who called Winter a “masterful” teacher, remembers his commitment to demonstrating would come into effect during games. Although Winter remained composed on the sidelines, he would sometimes let loose at halftime.

“Occasionally — without going into specifics — he would do a demonstration of how to go after a loose ball or how to do something in the locker room where he (would) actually give up his body and go after a garbage pail,” Falk said. “While he was serious, it became kind of comical on one or two occasions. Players got a big kick out of it.”

Major Upsets

Playing winning basketball in the Big Ten in the 1970s was no easy task. With Bob Knight’s Indiana dynasty, a solid Michigan program and a number of standout players including Magic Johnson causing havoc for the lesser teams in the conference, it was very difficult to win a lot of games during the winter months.

In addition, NU did not play an easy non-conference schedule. Winter always scheduled tough opponents like Marquette, Notre Dame and UNLV. The difficult slate, McKinney said, helped prepare the team for the Big Ten and was also a reason NU was always able to spring an upset.

In addition to its major upset over Kentucky in 1975, the biggest upset of the Winter era occurred on Jan. 29, 1977.

Earlier in the month, the Cats had travelled to Ann Arbor and were smoked by Michigan, 102-65, as the Wolverines fans laughed at NU. McKinney remembers what Winter said to him in the locker room.

“After the game, he challenged me. He didn’t think that I give it my best effort that day against (future first-round pick and All-American Rickey Green),” McKinney said. “His words never left my head for the rest of the season.”

When the Wolverines, now ranked No. 2 in the country, travelled to McGaw Hall on Jan. 29, McKinney said he knew they were going to win, even if people thought he was crazy to say so.

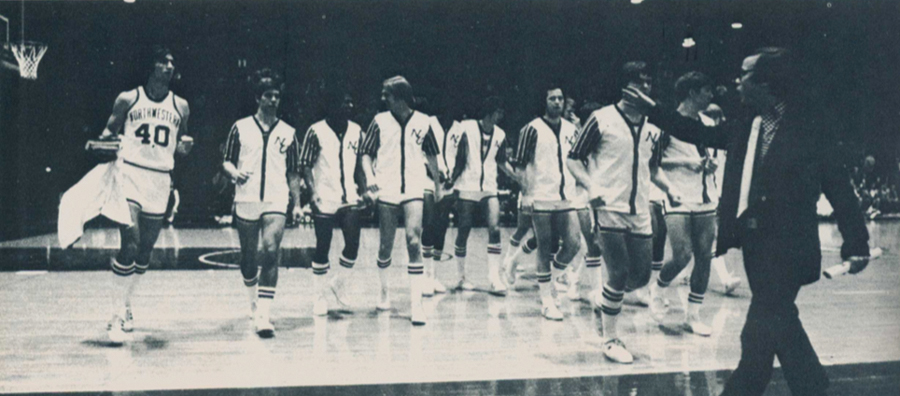

McGaw Hall during the 1976-77 season. When Winter was hired at Northwestern, he had the old basketball floor from the gym at Kansas State shipped and installed at McGaw Hall.

Against Michigan’s famous full-court press, McKinney and fellow guards Jerry Marifke and Bob Hildebrand did an excellent job breaking down the defensive pressure. And while the Cats neutralized the Wolverine defense, they did a stiflying job on their end too, holding Michigan to a shooting percentage under 40 percent.

Leading the attack was McKinney, who the Wolverines coach Johnny Orr said at the time was “absolutely phenomenal.” The senior finished the contest with a game-high 29 points as NU defeated Michigan, 99-87.

“Those were really exciting games where everything seemed to come together,” Caccese said. “And then you wonder to yourself, wow, can you do that every game? But you know wins frankly were very elusive.”

The End of the Era

Even though the Cats had their moments, most of the time, NU left the court without a win. The Cats struggled in all five of Winter’s seasons and only managed to claim double-digit wins one time.

“He wanted to be a winner and he hadn’t solved the riddle of how to be a winner at Northwestern,” Caccese said.

In articles from the time period, players expressed frustration with a lack of communication from Winter. It was also difficult for Winter to recruit the best talent available to Evanston due to NU’s strict academic standards. Winter’s Cats also struggled with consistency. Winter had expected to change the losing culture, and the administration expected him to do the same.

By the end of his fifth season, Winter had grown discontented with Cats. His plans to renovate McGaw Hall had gone nowhere and he openly expressed frustration to the media at the lack of money dedicated to the team. Winter began to look at other offers.

“I was in his office following the last game of the year and he had the job posting for Long Beach State on his desk. He made like a flip comment,” Caccese said. “‘They’re looking for a winning coach. Think I qualify?’”

Winter applied and he was accepted as the head coach of Long Beach State in April of 1978. He recommended Falk replace him at the helm of the program, which is what NU decided to do.

Winter finished his five years with a 42-89 record, which is a .321 winning percentage. In his four other collegiate homes, he would never finish his tenure with a record below .500.

Winter spent five years at Long Beach State, where he had a winning record, before he found himself back in the NBA.

Falk would be the coach of the Cats for eight seasons. In 1983 he brought the NU to the NIT for its first ever-postseason tournament. He said much of what he says as a coach can be attributed to Winter. He even gave his old mentor credit when looking back on the Cats’ victory over future NCAA Champions Michigan State in 1979.

When McKinney finished his career, he was NU’s all-time leading scorer with 1900 points. He went on to play seven seasons in the NBA, and worked with Winter again for one year in Chicago. He also credits Winter for helping him get to where he is in life.

“I can tell you this,” McKinney said, “had I not played for Coach Winter, there’s no way I would have ever played in the NBA.”

For all his coaching success, McKinney said people don’t talk as much about the outstanding man Winter was during his life. He said Winter never let fame change his attitude or let fortune or wealth corrupt his core values.

Winter’s legacy at NU is not as cut and dry as his overall basketball legacy. Winter, like so many Cats coaches over the years, was not able to break NU out of the perpetual-losing cycle. But he still developed McKinney into an NBA talent and his mentee Falk brought the Cats to the postseason for the first time ever, in addition to their historic upsets.

And while his plans to renovate McGaw Hall were never used during his time at the school, McKinney said when the arena was finally renovated in the 1980s, it was pretty much exactly what Winter drew up.

Winter may not have been a winner at Northwestern, but his impact on the program and the sport did not end the moment he left campus.

“He dedicated himself so much to the game of basketball that you have to admire that,” Svete said. “It has to be recognized.”

Email: peterwarren2021@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @thepeterwarren