In Focus: As Feinberg surpasses initial ‘We Will’ fundraising goal, progress on tuition-free initiative lags behind

May 7, 2018

Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine made a rare announcement in 2014: It would create an endowment large enough to provide a tuition-free education to all medical students.

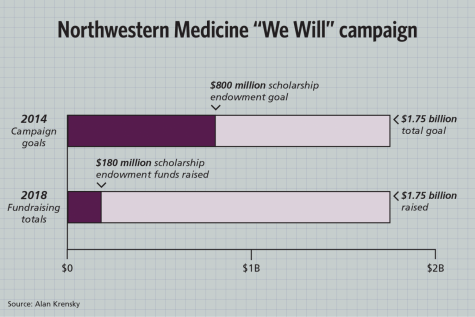

The initiative is part of the University’s “We Will” campaign, a $3.75 billion fundraising effort that has transformed Northwestern by supporting expensive construction projects, significant research endeavors and an expansion in global reach. For Northwestern Medicine, “We Will” entailed raising $1.75 billion toward endowed professorships, grants and fellowships, new facilities and the construction of a biomedical research building.

It also meant creating an $800 million endowment that could allow all students to attend Feinberg on full scholarships.

Several administrators said they support the tuition-free initiative, hoping it will better allow students to matriculate and ultimately specialize without being restricted by the prospect of heavy debt.

Yet, despite Feinberg having reached its $1.75 billion goal this year — and setting a new target of $2 billion — donations to the scholarship fund have lagged behind the other fundraising areas, said Dr. Alan Krensky, vice dean for development and alumni relations. He said the scholarship endowment currently stands at $180 million, or 22.5 percent of the desired amount.

The goal of a tuition-free Feinberg education is “aspirational,” Krensky said. And with less than one-fourth of funds raised, the program’s future remains unclear.

“We have gotten a lot done and it’s terrific, but I would say we still have a long way to go,” Krensky said. “We do like to sort of kiddingly say, ‘We are only one gift away.’”

Removing financial constraints

Dr. Vivian Roy (Feinberg ’13) worked for a few years before attending medical school but said the money she saved was not enough to cover four years of tuition and rent in Chicago.

Roy preferred Feinberg over her other options for its curriculum and camaraderie: Everything “just fit well,” she said, except the money. Northwestern did not offer her any merit-based aid, but a different institution did. After reaching out to Feinberg about her situation, Roy said she was told there was nothing they could do.

But several days later, she received another message with much better news: If she committed to Feinberg, the school would offer Roy $40,000 per year through a scholarship from the Satter Foundation.

“I got lucky,” Roy said. “I asked them to match the scholarship money that I had at this other school and they actually went above and beyond.”

The scholarship helped draw Roy to Northwestern, where she decided to specialize in physical medicine and rehabilitation after participating in a program through the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab.

“That got me interested in the field of rehab, so that was actually kind of fortuitous because I don’t know if I would have been exposed to that field if I hadn’t come to Northwestern,” Roy said.

The field she chose is one of the 20 lowest-paying medical specialties, according to a report published in March by Doximity, a networking service for health care professionals. Roy said she probably would have specialized in this area regardless of the Satter scholarship, but having the aid made it easier because she left Feinberg without significant debt.

Last year, medical students at Northwestern graduated with a mean debt of about $181,000. Nationwide, the mean medical education debt for the class of 2017 surpassed $206,000 among private institutions.

Krensky said debt can influence the field in which students specialize and where they choose to practice medicine. When planning Feinberg’s fundraising campaign, the school decided that helping students graduate debt-free should be a “centerpiece” of its efforts, he said.

“If you have the resources to offer free tuition to people, that does change the student body and who would choose to come, and make it possible to attract people who we may accept now but who don’t come for one reason or another,” Krensky said.

Currently, Feinberg’s financial aid packages can include loans, need-based grants and merit-based scholarships. Estimates for the total cost of attendance in the 2017-18 academic year surpass $85,000, with roughly $58,000 going toward tuition.

Currently, Feinberg’s financial aid packages can include loans, need-based grants and merit-based scholarships. Estimates for the total cost of attendance in the 2017-18 academic year surpass $85,000, with roughly $58,000 going toward tuition.

Cynthia Gonzalez, senior assistant director of financial aid at Feinberg, told The Daily in an email that the school is committed to increasing scholarships, as financial considerations are generally part of prospective students’ decision-making.

But in her experience, she said she found that students typically choose which school to attend based on a “holistic overview,” not financial circumstances alone.

Still, University President emeritus Henry Bienen — chair of the Northwestern Medicine fundraising campaign — said medical students’ paths diverge after graduation. Although average wages among doctors are high, some doctors earn less by working in public health or low-income communities, he said.

“If you are already coming to medical school with debt from undergraduate school, you could be very leery on taking on a lot more debt in the years you are in medical school,” Bienen said. “It could be many years out before you get clear on your financial obligations.”

Satter scholars

Though large individual gifts are not the norm, some donations have had a significant impact on financial aid at Feinberg.

In 2015, Northwestern alumni Muneer Satter (Weinberg ’83) and Kristen Hertel (SESP ’86) donated more than $10 million to the University’s “We Will” campaign. Nearly $8.5 million went toward the Satter Foundation Scholarship program, which supports three first-year Feinberg students with merit-based scholarships of $40,000 per year through the end of their third year, according to the program’s website.

“Kristen and I are committed to the goal of assuring a Northwestern education to promising future physicians and medical scientists,” Satter said in a 2015 news release. “These scholarships are investments that will ultimately benefit medical science and humanity.”

By that point, the Satter Scholars program had already provided scholarships to several Feinberg students, including Roy. Krensky called the Satter gift one of the school’s “biggest leaps” toward the tuition-free initiative, adding that Feinberg has not received a scholarship donation on the same scale since.

Multiple Satter scholars said receiving the scholarship went a long way in allowing them to focus on academics.

Dr. Ashish Sarraju (Feinberg ’14) said attending medical school on this scholarship was a “tremendous” opportunity. After graduating from Feinberg, Sarraju moved to Stanford University for a residency in internal medicine, and he said he was lucky to have finished medical school without going into significant debt.

“One can’t overemphasize the role that taking away that financial burden (plays),” Sarraju said. “You could really sort of go about your medical school days with a true smile on your face and a lightness in your heart. I think that’s a big deal.”

A 2018 study by the Association of American Medical Colleges projects that there will be a nationwide shortage of between 42,600 and 121,300 physicians by 2030. Among primary care physicians, the study predicts the shortage will be between 14,800 and 49,300 people.

Lower medical school debt could alleviate the physician shortage by encouraging students to pursue their desired medical field, regardless of future compensation, Sarraju said.

Dr. Patrick Hurley (Feinberg ’16) said the Satter scholarship was the reason he attended Northwestern. Cost was an important factor to Hurley, as his family was unable to pay for medical school, and the scholarship allowed him to take out loans only for living expenses.

Later on, Hurley said, he worried less about paying off those loans when he chose to complete his residency in psychiatry. The field is another one of the 20 lowest-paying specialties, according to the Doximity report.

Hurley added that he did not feel pressured to choose a higher-paying field to compensate for medical school costs.

“It really didn’t enter into my calculus,” he said. “I just chose it based on passion and enjoying treating psychiatric patients as opposed to which field would make me the most money.”

‘Revealed preferences’

Krensky, whose office raises money for the tuition-free initiative, said he and his colleagues focus on various forms of outreach, particularly to alumni.

Although Northwestern Medicine’s “We Will” campaign is ahead of schedule, Krensky said the influx of donations earmarked for scholarships has lagged in comparison to other areas. He added that he hopes Feinberg alumni will band together to support future medical students.

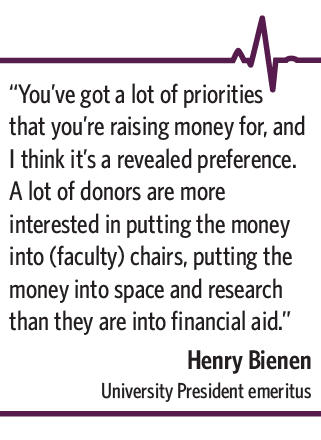

Bienen said some donors are strongly motivated by a desire to combat diseases like cancer and Parkinson’s, especially if they or their loved ones have been diagnosed. Other donors may prefer to support new institutes that can have a large impact on progress in research, he added.

“You’ve got a lot of priorities that you’re raising money for, and I think it’s a revealed preference,” Bienen said. “A lot of donors are more interested in putting the money into (faculty) chairs, putting the money into space and research than they are into financial aid.”

Krensky praised the campaign’s progress in raising money for various institutes, endowed professorships and innovation grants. He said a central component of the campaign was to “dramatically” grow Northwestern’s research endeavors, which required the construction of new buildings.

Following a $92 million gift from a Northwestern alumnus and his wife, Northwestern broke ground on the Louis A. Simpson and Kimberly K. Querrey Biomedical Research Center in 2015. The center, initially designed to comprise about 600,000 square feet, is slated to be completed next year.

“It is going to allow us to recruit new faculty, expand our research and expand the entire Northwestern footprint of research,” Krensky said. “It’s a very major part and that’s been our focus.”

Jay Walsh, NU’s vice president for research, said the University needs to regularly upgrade its facilities because of its “size and heft.” The biomedical research center, he said, will include space for Feinberg and the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, as well as room for scientists to conduct interdisciplinary work.

Using existing spaces for biomedical research can be challenging, as retrofitting buildings to handle current biomedical work requires significant effort, Walsh said.

Feinberg raises money in multiple ways, he added, from faculty members writing grant proposals to philanthropists making donations. Walsh said donors can support needs like specialized equipment, for which the University cannot easily receive other aid.

Overall, Bienen said, donors tend to be driven by the desire to make a significant impact in a particular area, such as research.

“That’s a worthy priority, as is financial aid, but if you believe in revealed preferences, you look at the data … and it tells you something,” Bienen said. “But that doesn’t mean you give up. You just say, ‘OK, we’ll do what we can.’”

A long road

Although Krensky called the tuition-free initiative an “aspirational” goal, he noted Feinberg has created more than 60 new scholarships since the campaign began. It is impossible, however, to control the rate of donations toward the $800 million endowment, he said.

“There is the hope that some huge donor will get us there, but the reality is it’s many more smaller donors each year, class gifts, various alumni, things like that, that move us closer to the goal,” Krensky said.

It would be tough to reach the $800 million goal through individual donors, Bienen said. Profits from inventions coming out of the medical school, however, could quicken the progress, he added.

Bienen recalled the drug Lyrica, which originated in a Northwestern chemistry lab and was first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2004. Due to an agreement with pharmaceutical company Pfizer, revenue from the drug significantly raised NU’s licensing revenue, money the University earns for allowing its copyrights and patents to be used by other companies.

Royalties from the drug brought roughly $1.4 billion into the University’s endowment, and Bienen said he used a significant portion of the windfall to support financial aid for Ph.D. students. Future University presidents, he added, could also funnel money toward scholarships.

Bienen said Feinberg has a number of discoveries “in the pipeline,” and that any future royalty streams could be used to increase financial aid for medical students, just as Lyrica helped those in Ph.D. programs.

“(These discoveries) are not a certainty — it’s a long road,” Bienen said. “It took years and years from the initial discovery of Lyrica to the time that we started getting money from Pfizer and then monetized the flow with a big company.”

Walsh said some new drugs are in clinical trials, which help determine their efficacy and safety. However, trials can also reveal previously unknown side effects, he said, and it is impossible to predict whether “a big Lyrica 2” will come along and provide a large royalty stream.

“While we always hope that this will happen,” Walsh said, “we also recognize that that is certainly not a good way to budget.”

Barriers to entry

Lisette Corbin, who graduated from Weinberg in the fall, said she has felt discouraged by the medical school application process “every step along the way.”

The Medical College Admission Test costs more than $300 and test preparation courses can cost a few thousand dollars. Students then pay for primary and secondary applications unless they qualify for fee waivers, and often those who make it far enough in the application process are asked to interview, which can add further costs for travel and housing, Corbin said.

Despite these costs, she said, applying to medical schools doesn’t compare to the price of tuition itself.

To minimize future debt loads, Corbin said, some students aim for their state schools — which may offer lower tuition than private institutions — or strive for competitive private schools that can offer hefty scholarships or loan-free financial aid packages.

Annie Nielsen, who graduated from Weinberg in the fall, said it is also important to consider the costs of living during medical school, as they may generate an additional financial burden.

Some students, however, don’t have the freedom to choose between different cities or aid packages. Nielsen, who intends to begin medical school in the fall, said she received one acceptance and was placed on multiple waitlists.

As she prepares to submit her applications, Corbin said the medical school application process is yet another example of the way low-income students are disadvantaged in higher education.

“A lot of schools are moving in the right direction by being loan-free and offering scholarships and trying to do what they can to reel in costs,” Corbin said. “But I think at the end of the day, it’s a system that favors the wealthy and the advantaged, and it makes it that much harder for people who aren’t from that privileged background to have a chance.”

A nationwide effort

Feinberg is not the only medical school trying to provide full scholarships for its students.

At the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, all students receive a full-tuition scholarship. The school enrolls roughly 30 new students each year.

Columbia University, meanwhile, received a $250 million donation last year from Dr. P. Roy Vagelos and Diana Vagelos. About $150 million of the gift is funding an endowment that will provide full-tuition scholarships to those with the greatest financial need and will eliminate loans for those who qualify for financial aid, according to a Columbia news release. Columbia and Northwestern enroll a similar number of first-year medical students — just over 150.

Vagelos said he hopes the donation will allow medical students who graduate from Columbia to pursue specialties that are comparatively less lucrative, such as pediatrics and family medicine, according to The New York Times.

The tuition-free movement has also extended to the west coast. In 2012, Hollywood mogul David Geffen donated $100 million to create a scholarship fund for medical students at University of California, Los Angeles. The scholarship, given to roughly 20 percent of incoming UCLA medical students, covers full tuition and other expenses for all four years.

Some of these financial aid programs are need-based, but others like the Satter Foundation scholarship at Northwestern and the Geffen scholarship at UCLA are based on merit.

In a January interview, University President Morton Schapiro noted the push among some medical schools to provide a tuition-free education and said it is important for schools to take into account students’ financial needs.

Schapiro said letting students with “tremendous wealth” attend medical school for free would be a “misallocation” of scarce resources.

“But if it’s somebody from a lower-income family who is going to take out tremendous debt … I think reducing the price for people who don’t come from wealthy backgrounds makes a lot of sense,” he said.

Justifying the investment

While medical schools are expensive, their graduates have strong job security and “excellent” income potential, said Julie Fresne, senior director of student financial services and debt management strategies at the Association of American Medical Colleges.

With current loan repayment plans — in which borrowers pay based on income, not level of debt — Fresne said medical school graduates can pay a manageable amount each month.

“I am not discounting the high cost — or, for some people, the high debt — but of all professions that are out there, barring any unusual circumstances, these graduates should be able to get a job that enables them to not only repay their education debt, but to provide for (a) secure living and retirement,” Fresne said.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, direct unsubsidized loans for graduate or professional students currently have a 6 percent interest rate, which is 1.55 percentage points more than equivalent loans for undergraduates.

Some students’ debt levels play a moderate to strong influence on their specialty choice, Fresne said, but other factors tend to hold greater weight. It is more common to choose one’s specialty based on factors like a past mentor or a preferred lifestyle, she said.

Despite the rise in medical school tuition and the high mean debt, Fresne said she strongly believes that a medical education is still a good investment, particularly because of income-driven repayment plans.

“There is no reason that a medical school graduate should not be able to practice the specialty that speaks to them and expect to repay their student loans manageably,” she said. “Cost should not be a deterrent.”

Funding Feinberg

Sean Posada, who recently finished his third year at Feinberg, said he paid close attention to finances while applying to medical schools. If Northwestern relieved medical students’ debt or followed through on the initiative to provide free tuition, Posada said many students’ experiences would be much less stressful.

“I definitely think that the initiative Feinberg is doing is a very ambitious one, and one that I support 100 percent, because my undergrad experience was actually enhanced by the fact that I was lucky enough to receive a full financial aid package,” Posada said. “Whereas now in medical school, I still prioritize my studies — but finances are always on the back of my mind.”

Roy, the Satter scholar and 2013 Feinberg alumna, said the school’s initiative to provide more scholarships to students is “for the best.” The Satter scholarship made it easier for her to pursue a fellowship after her residency, and Roy added it would have been harder to support her 2-year-old child if she still had debt.

She took out some loans to cover the cost of living in Chicago, but Roy said she was able to pay them off soon after graduating from Feinberg. As she nears the end of her fellowship, Roy said she plans on returning to Feinberg as a faculty member and physician later this year.

Universities’ efforts to subsidize tuition for other students can also address the national doctor shortage, although there is no simple solution to the issue, Roy said.

Roy said she believes she would not have ended up at Northwestern if Feinberg had not offered her the Satter scholarship about 10 years ago.

“This was the right school for me,” Roy said, “and I’m just glad that I was able to come here and chase my dream without really having to worry about student loans and paying off debt.”

Email: peterkotecki@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @peterkotecki