In Focus: Fifty years after Bursar’s Office Takeover, Northwestern reconciles continued parallels in black student concerns

May 3, 2018

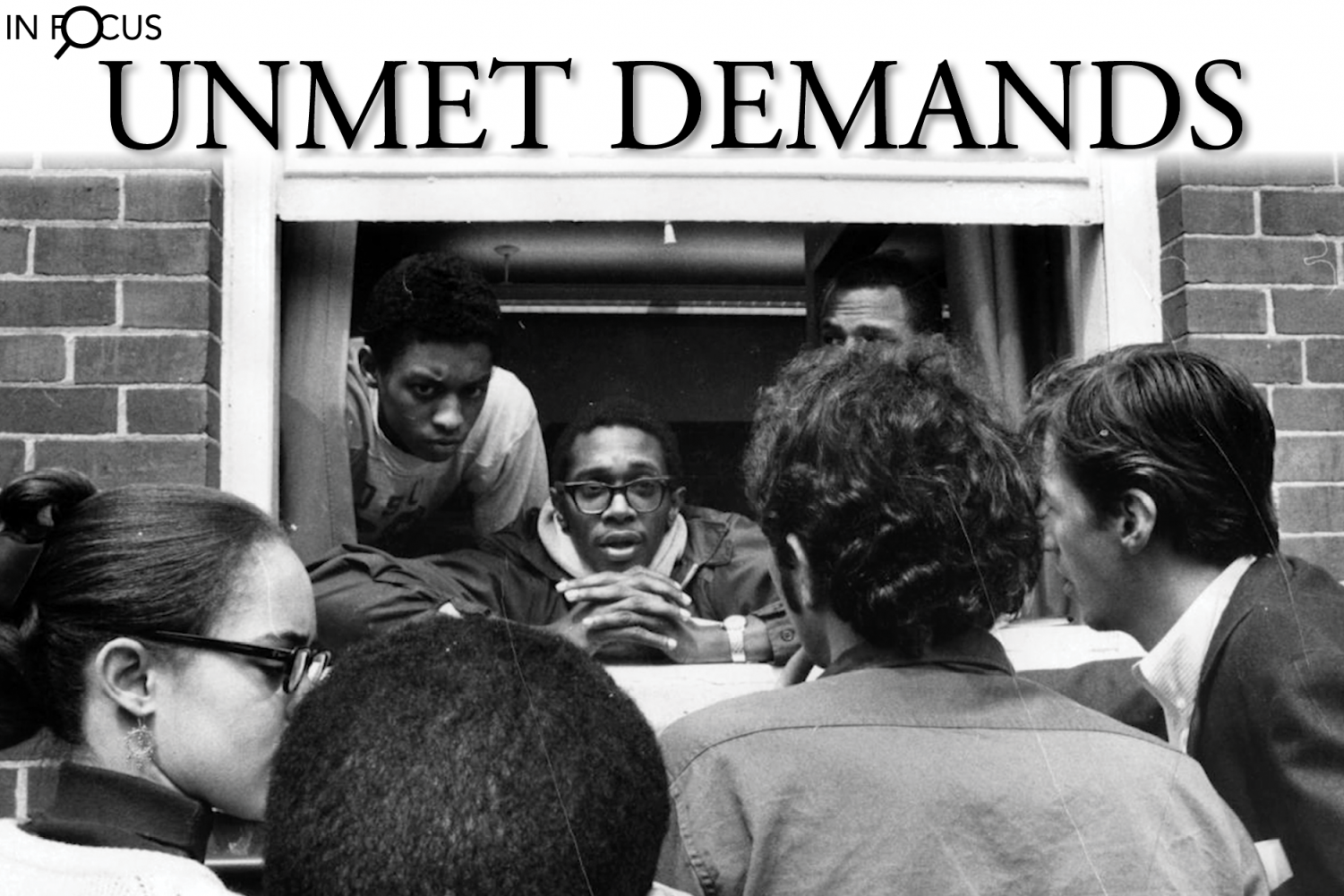

Kathryn Ogletree woke up around 6 a.m. after a sleepless night. Hours earlier, black students had convened to finalize plans for an upcoming campus protest. Leading their meeting was the 18-year-old freshman, who was critical in mobilizing the upcoming 38-hour sit-in that forever shifted the course of the University’s relationship with black undergraduates.

It was May 3, 1968.

Less than two weeks prior, black students had presented administrators with a list of demands. But they weren’t satisfied with the University response. After continued back-and-forth, students felt it was time to escalate from discussion to confrontation.

As she left her Allison Hall dorm room, Ogletree (Weinberg ’71, Graduate School ’76) readied herself to usher about 106 other black students into Northwestern’s Bursar’s Office at 619 Clark St. — home to financial records, cash holdings and the University’s business operations.

“We were nervous, but we knew this would get their attention,” Ogletree said. “And we were just getting started.”

After hanging a sign outside reading “Closed for business ‘til racism at NU is ended,’ the students created a diversion across campus, blocked the entrances and occupied Bursar’s Office overnight.

In the morning, Ogletree and nine other students met administrators and faculty in Scott Hall to begin negotiations. Back on the table was their list of demands, which included raising the representation of black students on campus to at least 10 to 12 percent of each incoming class and hiring more black faculty members. Students also called for the University to provide space for a black student union and to publicly acknowledge institutional racism as a demonstration of cultural sensitivity.

“Our sides were at polar at opposite positions when the Takeover started,” Ogletree said. “But when we actually started meeting, there was some appreciation that the administrators were finally trying to understand what they hadn’t before.”

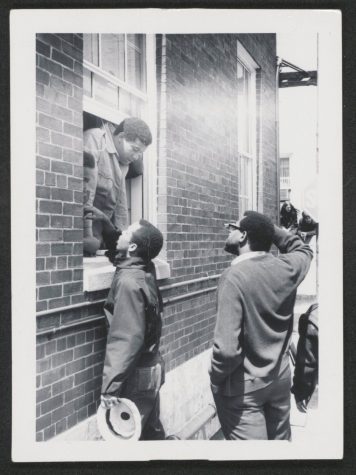

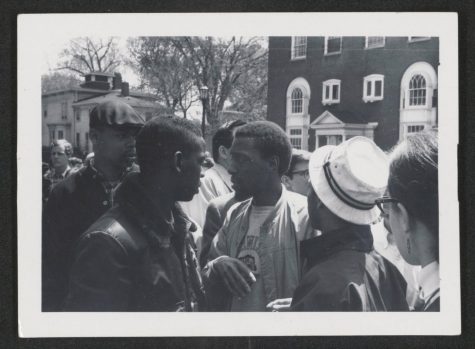

Northwestern student Stephen Broussard (Medill ’70, Law ’73) exiting the Bursar’s Office on May 3, 1968. Students blocked the entrance to the building to stop police from forcibly removing protesters inside.

Later that evening, students accepted the terms that the University had committed to in the so-called “May 4th Agreement” and left the Bursar’s Office, ending the day-and-a-half protest.

Ogletree said in pushing for more despite administrators’ initial acquiescence, students were directly focused on bettering the experiences of those to come after them. In some aspects, that’s what happened, according to Charla Wilson, the University archivist for the black experience. The significance of what she calls the “first major protest” at Northwestern can still be felt today, from its direct role in prompting the establishment of the Black House to the development of the African American Studies Department.

Yet a half-century later, the bulk of demands Ogletree and her peers advocated for were either never met or only achieved in the short term. Many have resurfaced throughout the past 50 years in separate protests, with similar concerns raised across decades. And in more than 30 interviews with The Daily, current Northwestern students and alumni used near-indistinguishable language to describe their struggles on campus.

Data also shows black students remain uniquely displeased with their time at the University. Their satisfaction with their campus experience lags behind that of every other racial and ethnic group on campus, senior surveys show, and as recently as 2016, was on the decline. Only 12 percent of graduating black students in 2016 reported feeling “very satisfied” with their undergraduate education — compared to 35 percent a decade earlier.

No other racial or ethnic group surveyed averaged rates under 20 percent that year.

Echoes of the past

Nearly three years ago, Communication senior Jade Mitchell found herself at the front a group of about 300 students as they disrupted a groundbreaking ceremony for the new lakeside athletic complex. Students were protesting both a lack of representation and resources for students of color and institutional racism at Northwestern as University administrators, alumni and donors gathered to celebrate what would become a $260 million athletic facility.

“That was the first time it felt like they took notice,” said Mitchell, who is co-president of CaribNation, a cultural student group. “They were livid that we were in there. Sometimes you have to move people to anger to get them to listen.”

In 2015, Mitchell said, many black students felt that the University didn’t listen to them. The demonstration occurred amid University discussions surrounding the decision to move administrative offices into the Black House.

Later that November, various student organizations aligned to release a list of 19 demands related to the experiences of students of color — which grew to 34 by its final iteration in January 2016.

The list included increasing the total percentage of black students to at least 10 percent by 2020, tripling the number of faculty of color by 2025, expanding Black House resources and publicly acknowledging national tragedies within communities of color.

Three days after the protest, the University canceled proposed changes to the Black House. But Mitchell said the issue reflected an institutional disconnect with the black student experience. She said it illustrated a need for the University to be “more culturally sensitive.” Unbeknownst to her, she was using the same phrase as the student activists in 1968.

Reconciling parallels

African American studies librarian Kathleen Bethel, who joined Northwestern in 1982, has served on two University task forces dedicated to studying the black student experience on campus — one over 20 years ago and another in 2016. Little has changed in that time, she said.

The more recent study — which led to the landmark 2016 Black Student Experience Task Force Report — brought up the same grievances as the initial one, conducted during the 1995-96 academic year in response to campus incidents surrounding racial issues.

“We could have taken the cover sheet off the first report and put it on the second one,” Bethel said. “It pretty much said the same exact thing.”

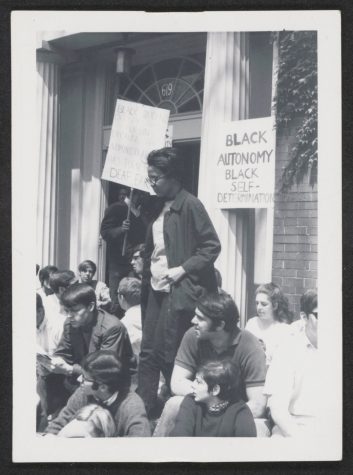

Northwestern students gather outside the Bursar’s Office during the takeover. The poster on the left reads: “Black students occupy this building because the administration has turned a deaf ear.”

Though Bethel said she’s seen a “really proactive” response from the University to more recent black student concerns, she wondered how much longer it will be until change sticks.

Wilson called the similarities between demands then and now “eerie,” but emphasized the courage of students in the 1968 protest, considering the national context at the time: On other college campuses throughout the country, protesters had been injured and killed.

Still, Wilson said that even 50 years later, students continue to say they feel “exhausted being black on campus.”

Those continued struggles led Jeffrey Sterling (Weinberg ’85) to co-author a book chronicling the evolution of black students’ experiences on campus. Their feelings on campus haven’t just shared surface-level similarities over time; some current students use the “exact same words and phraseology” as the protesters in the 1960s, said Sterling, president of the Northwestern University Black Alumni Association.

In a February interview with The Daily, Provost Jonathan Holloway acknowledged that “painful echoes” still surface harkening back to the takeover. Still, campus inclusion and diversity efforts have seen “radical positive improvements” at universities including Northwestern, he said in April.

“Anybody who says we are no further along than we were 50 years ago is just wrong, period,” Holloway said. “However, if they were to say we’re not where we need to be, they’re right.”

Lauren Lowery (McCormick ’89) — former vice president of NUBAA — said there’s a clear reason why the same obstacles persist: the University “banks on the fact that the memories are short.”

Earlier this year, Lowery co-founded the NUBAA Archives along with Sterling because after a trip to the University Archives, she realized little to nothing had been compiled on the history of black students at Northwestern.

“They didn’t value over the 140 years of Northwestern — or whatever how many years it is now — black students and black experiences,” Lowery said.

“Unfortunately, no one has people of color’s interests at heart other than themselves. So if we continue to come and go… and when Northwestern administrators don’t have interest, then the same things continue to occur.”

A matter of numbers

“Wait a minute. What happened?”

That’s how Weinberg junior Dante Gilmer, who participated in the 2015 disruption of the groundbreaking ceremony, reacted upon seeing the parallels in demands made nearly 50 years apart.

Today, one of the biggest challenges black students face, Gilmer said, is the that they just don’t have many people who look like them — and might be able to relate to their experiences — on campus. Establishing a sense of community is challenging when the total student body is still less than 10 percent black, Gilmer said.

After the 2016 Black Student Experience Task Force Report was released, administrators and University leaders prioritized three of the 14 recommendations for the 2017-18 academic year, including increasing the number of black students, faculty and staff.

Associate provost and chief diversity officer Jabbar Bennett, who oversees a committee that focuses on this recommendation, said he’s working to ensure the population of black students on campus is representative of the country. In doing so, Bennett said it’s important for the University to concurrently prioritize increasing available resources and financial aid.

Though black students make up one-tenth of the class of 2021 — the highest percentage in recent history, said executive director of Campus Inclusion and Community Lesley-Ann Brown-Henderson — only 6 percent of all undergraduates identified as black in fall 2017, with a separate category for multiracial students, according to the Northwestern Data Book.

Many current black undergraduates said they are not represented sufficiently in all majors and programs.

Communication junior Elliot Sagay said that both at Northwestern and within his theater major, the number of black students is noticeably small. In last year’s graduating theater class, he recalls two black students, and while his cohort feels larger in comparison, it’s still not enough.

“It’s important to celebrate our steps forward, to celebrate our victories, but I think it’s also important to remember that sometimes those victories are just a small step, and that we need to keep walking,” Sagay said, “we need to keep running in order to get to where we actually want to be.”

FMO coordinator Kasey Brown said enrolling more black students isn’t enough; Northwestern must also consider the “other variables” they face — compared to white students — once they’re here.

Although NU’s current first-year class is 10 percent black, Brown said it’s important to realize “how little progress” has been made in 50 years.

“There’s so much room we could have grown, but we celebrate that 10 percent because we really don’t know the history,” Brown said, “and the University knows we don’t.”

“We look nothing alike”

Several black students said the erasure of their identities extends to small, everyday instances on campus.

Earlier this year, Sagay wrote a play titled, “What’s in a Name?” for “Black Lives, Black Words” — a campus iteration of an international project aimed at providing a platform for black actors and playwrights.

Sagay’s piece dealt with the subtle biases and ignorances that can manifest when non-black faculty and students mispronounce or forget the names of black students — behavior he said has impacted his NU experience, like when the production “In the Red and Brown Water” opened in the fall.

“When it closed, I got congratulated by at least five people in the span of a week for being in that show,” Sagay said. “I had made no appearance in it.”

When faculty members too began mistaking him for other black students, the issue became “much more pressing,” he said. Other black theater students shared similar experiences with The Daily.

“We’re going to an institution where we’re paying for our education,” Sagay said. “Messing up the names of people of color is not the sort of example that any teacher should be allowed to set.”

After the disruption of the groundbreaking ceremony, students demanded the University triple the number of faculty and administrators of color by 2025. They also separately demanded special attention be paid to the theater department.

According to the Northwestern Data Book, 3.5 percent of tenure-line and full-time faculty in fall 2016 — including those in graduate schools — were black.

Sagay said one of the “most valuable” aspects of his experience in the department has been having professors of color.

But having so few among faculty, he said, has been challenging. Three black theater professors — Harvey Young, Melissa Foster and Aaron Todd Douglas — were in the department when he arrived. Young has since left the University.

Karen Taylor, president of NU’s chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers, said she has only had one black professor — for an African American studies course — during her six quarters on campus.

Taylor too said she’s been called the wrong name in her engineering classes. Through a number of courses, the McCormick sophomore said, faculty members mistook her for another black student.

“The professor confused us for the whole quarter. It happened again the next quarter with a different professor, and then happened again the quarter after that with a different professor,” Taylor said. “Meanwhile, it’s just us two the whole time. I don’t expect everyone to get everyone’s names right on the first try but … it’s only us two, and we look nothing alike.”

Former and current black NU students agree that a higher number of black faculty could increase student inclusion while preventing microaggressions or racist incidents from occurring as often in the classroom.

James Turner, president of the Afro-American Student Union, talks to the press on the day of the Bursar’s Office Takeover. Turner was a lead negotiator in the takeover.

Brown-Henderson co-chairs a team focused on strengthening student and faculty relations. The group aims to tackle one aspect of another recommendation prioritized for this academic year: listening to black students regularly, not just in times of crisis.

The team, Brown-Henderson said, understands that black students have had interactions with faculty members that they feel are inappropriate. Now, she said they’ve been figuring out what resources for help are available in those instances and where gaps might lie.

What black students experience in higher education is often a product of “systemic and institutional inequalities, and really institutional racism,” she said. But moving forward, Brown-Henderson said she’s confident in the potential to create real change at the University as “more structure and capacity” exists internally now than when she first arrived in 2012.

Bursar’s Office Takeover participant Debra Hill, who graduated from the School of Education in the 70s, said she never had a black professor during her time at NU, and she backed efforts to increase representation within faculty as a result.

During a summer program at the university in the late 1960s before her freshman year, Hill said a white counselor questioned whether she was “Northwestern material.”

“The counselor that I was assigned just told me to my face that he did not think that I was going to be successful at Northwestern,” Hill said. “There was no black faculty for me to go to, to share that with, to say, ‘So, how do I deal with this?’”

An alienating atmosphere

Bursar’s Office Takeover participant Victor Goode (Weinberg ’70) said he never experienced overt racial harassment during his time at NU.

“But some of my friends did,” Goode said. “That created an atmosphere that led me to believe if it can happen to them, it will happen to me at some point.”

A sense of “alienation” from the greater NU community, he said, was palpable throughout the University and had differing effects on black students.

Ogletree, the Bursar’s Office Takeover leader, recounted a range of racist incidents against black students during her time at the University: white students throwing beer cans out of windows at them, administrators disciplining them unfairly and faculty members treating them as an “object” for culturally educating others.

Half a century later, students say while overt incidents may be rare, the feeling remains. According to the 2016 Black Student Experience Task Force Report, less than half of respondents agreed that NU is welcoming for black students.

Justin Clarke (Weinberg ’13) said a lot of “racially-based nonsense” also occurred during his four years as an undergraduate.

The former FMO coordinator said incidents like the “Racist Olympics” largely characterized the environment at the time. In 2012, members of the Ski Team hosted a “Beer Olympics”-style contest in which attendees wore culturally insensitive costumes, including Native American headdresses.

“Subtle forms of racism” and “identity-based aggression” like that continue to remain issues, he said.

“You may not have someone walking up to you and calling you a racial epithet on Sheridan. But I had people during my time here walk up to me like, ‘Hey, are you an athlete?’” Clarke said. “I was 5’9”, maybe 120 pounds, do I really look like a Division I football player?”

Weinberg freshman Taylor Bolding said efforts to make campus more diverse and inclusive first require a committed “changing of the campus culture” to address the systemic problems existing within Northwestern.

Earlier this year, the University sent a Campus Climate for Diversity survey to undergraduate and graduate students. Brown-Henderson said its insights will be valuable in moving forward to tackle these concerns.

Earlier this year, the University sent a Campus Climate for Diversity survey to undergraduate and graduate students. Brown-Henderson said its insights will be valuable in moving forward to tackle these concerns.

But for black students on campus now, Bolding said the environment can be “very off-putting.” For example, she said, when a friend and prospective student visited campus during last month’s Wildcat Days, he quickly knew Northestern wasn’t the right fit for him. Comparing the University to the other schools he’d visited, Bolding said her friend told her it felt much less inclusive for nonwhite folks.

“I was walking across Sheridan and I just got so angry and fed up,” Bolding said. “My friend’s only been here for a day and he’s saying nothing but truth: This place wasn’t built for students like me, or students of color in mind.”

Feeling heard

Bennett said the University has place a higher priority on black student engagement since the 2015 protest.

He cited the establishment of community dialogues, a Northwestern initiative created to address concerns from the protest. The sessions continue to provide administrators valuable opportunities to examine issues salient to students, he said.

Brown, the FMO coordinator, said the dialogues often feel like they’re not really for students, but more of a way for the University to continue “checking off boxes.”

Sessions regarding the Black House and black student experiences should have been held at the Black House, Brown said — instead they were held at central spots across campus. Moving forward, she said if the University wants black students to attend the sessions, administrators should be more intentional when planning them.

Gwendolyn Gissendanner, who participated in the 2015 protest and graduated from SESP in March, said she’s seen “clear communication” between black students and upper-level University leadership in the last three years.

Still, as many of the students who interrupted the groundbreaking ceremony have left or are about to leave campus, Gissendanner said she’s concerned as to whether the University will continue to focus on improving black students’ experiences with less accountability.

“I fully understand that … all of these things do take time,” Gissendanner said. “I do get worried about the amount of time that Northwestern spends doing dialogues and doing listening sessions and that it’s really just a way to appease whoever started the momentum until they’re gone.”

Leaving a legacy

Despite the challenges she’s faced over the past four years, Brown said she has a clear message for peers who look like her: “it’s a great time to be black on this campus.”

Though it’s easy to believe issues will remain, she said understanding what student activists fought for 50 years ago shows current undergraduates they don’t have to settle.

“The fact that we know all this history and we can see all the imperfections this University has, pushes us to do more,” she said. “We can leave an impact and make this place better for the next black students that are going to come after us.”

When he was an undergraduate, Clarke said the Bursar’s Office Takeover was universally known throughout communities on campus. Many current students — both black and nonblack — interviewed by The Daily said they had never heard of it prior to University-wide announcements over the past few months.

Clarke finds that “really disappointing.”

Still, with the increased awareness sparked by the 50th anniversary, Clarke too said students should be energized to be on campus. They can have a say in what their experiences on campus look like, he said. Short-term progress may feel elusive, Clarke said, but students can look to the 1968 protest as assurance their voices matter.

“The takeover should never be forgotten — to hold the University accountable moving forward, but also to keep a sense of pride in that this is what was fought for, and this is what you get to have,” Clarke said. “This is why you still get to demand certain things of the University. Because those people came before you, and they did it first.”

Email: closson@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @troy_closson