In Focus: With demand for greater accessibility, Northwestern staff, students aim to close institutional gaps

March 9, 2018

Accessibility does not rank highly on Northwestern students’ list of priorities.

In one section of Associated Student Government’s most recent annual analytics survey, Northwestern students were asked to allocate points among 16 prompts, said Austin Gardner, ASG’s vice president for accessibility and inclusion. Of the options, increasing funding for AccessibleNU ranked 14th on average, Gardner said.

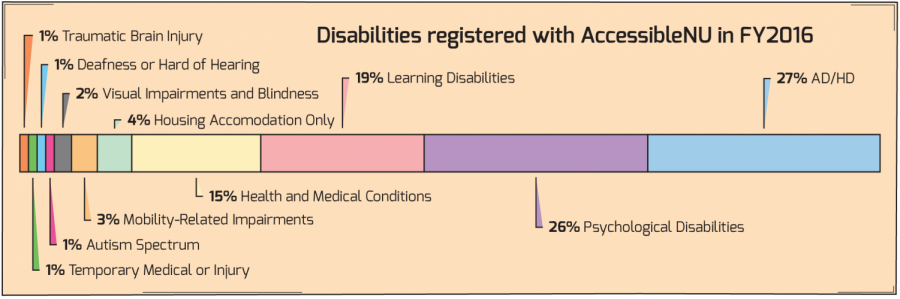

According to a January report by the Northwestern Accessibility Council, 2 percent of students registered with AccessibleNU during Fiscal Year 2016 were blind or visually impaired. The study — which details different ways Northwestern’s campuses can be made more accessible for students with these and other disabilities — is one of a few steps the University has taken to better address accommodations for students and staff.

Students with vision disabilities usually require additional accommodations in the classroom, such as enlarged course materials and extended time on assessments. Outside the classroom, these students may face obstacles like poor signage and obstructed walking routes.

As an increasing number of students seek assistance on a campus not originally set up to accommodate their disabilities, Northwestern staff and students are taking steps to close academic and institutional gaps. In the meantime, students with disabilities grapple with unique needs and challenges.

The AccessibleNU office, which works with more than 1,050 students, currently has five full-time staff members and one employee who splits her time between AccessibleNU and Counseling and Psychological Services.

Despite University efforts to make campuses more accessible, however, students with vision disabilities face barriers that able-bodied students and administrators may not even consider.

Fouad Hassan, a Communication senior at Northwestern University in Qatar who is legally blind, said accessibility needs differ widely even among students with similar disabilities. Because of this, Hassan said he is unsure if college campuses will ever accomplish “100 percent accessibility.”

“Being deaf or being blind have different levels,” Hassan said. “It makes it difficult for even people whose job it is to promote accessibility to fully accommodate everyone.”

Making Northwestern accessible

The number of students registered with AccessibleNU has increased significantly over the past 10 years, said AccessibleNU director Alison May.

May (Communication ’02) said there were only about 300 students registered with the office when she began working there in 2007. Now, about 9 percent of undergraduate students — roughly 750 out of the more than 1,050 served by the office — are registered with AccessibleNU, May said.

She said the uptick in the number of students served is partly due to the lengthy adoption process of the Americans with Disabilities Act, which became effective in 1990.

AccessibleNU works with any students taking for-credit classes, including online students and those in the School of Professional Studies, May said. Students with disabilities face many difficulties navigating life on campus, and within the constraints of the quarter system, even figuring out when to schedule doctor’s appointments can pose a challenge, she said.

“Our goal and mission is to provide them equal access via reasonable accommodations or adjustments,” May said. “The students that we work with in the office are just some of the brightest — because they have to be.”

The AccessibleNU office currently works with 16 students who have some form of visual impairment, and 17 deaf or hard of hearing students, May said. The vast majority of students AccessibleNU serves have primary conditions including long-term psychological conditions, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorders and learning disabilities.

“We’re trying to do more, especially as the numbers grow, to build accessibility more broadly into campus classes,” May said. “We’re promoting the idea that accessibility is a campus-wide responsibility.”

Accessibility Council report. Graphic by Colin Lynch.

In its report, the Northwestern Accessibility Council recommended the University’s provost advise faculty on the benefits of sharing class notes or PowerPoint presentations with students. And for faculty who do not usually share their notes, the council recommended that they share them with students whose accommodations include note-taking or recording assistance.

Last summer, AccessibleNU launched a universal design pilot program intended to make courses more accessible. The pilot provided professors with stipends to redesign their courses to be more inclusive, May said.

Universal design includes having professors provide captions for videos, putting slides online or sharing notes with the class, May said. Examples like this promote accessibility, she said, helping not only students with disabilities but also those whose first language isn’t English.

ASG president Nehaarika Mulukutla said the student government donated about $7,500 to AccessibleNU earlier this quarter to continue funding the pilot program.

Though the Weinberg senior noted it isn’t ASG’s responsibility to fund these sorts of initiatives, she said she was “really grateful” that they were able to use money left over from a budget surplus to assist the office.

“At the end of the day, no matter whose responsibility or job (it is), the most important thing is that (AccessibleNU) is getting funded and that these students who need these resources … can still get the best education possible,” Mulukutla said.

Advocates on campus

Although some students with disabilities come onto campus already knowing how to handle them, they can run into additional barriers, like engaging with other students or Northwestern’s competitive environment.

Tommy Carroll (Medill ’15), who is blind, said his experience navigating Northwestern was largely positive. Carroll, who is from the nearby suburb of Glenview, was the only fully blind student during his four years at NU.

He said he and his mobility instructor — who he had known since preschool — did an orientation of campus before his freshman year.

Still, he said the best way to acclimate to campus was by simply being here, by building muscle memory and by taking classes in different areas. He said adapting wasn’t too shocking because he has been blind since he was 2 years old.

“My experience is pretty good just because my needs are something I had spent my entire life dealing with,” Carroll said.

While he was at NU, Carroll said there was not a particularly strong community for students with disabilities. Part of this is because the University’s competitive environment makes it hard for people to be proud of marginalized identities, Carroll said.

Carrie Ingerman, a project lead on ASG’s accessibility and inclusion committee, said she is currently working to create an affinity space for students with disabilities. The SESP junior said she plans to launch the space, which will provide a support network and avenue for discussion, next week.

“Recognize that people with disabilities are incredibly successful and that there are many students on our campus with disabilities, both visible and invisible,” Ingerman said. “We as a university have a really hard time across identities accepting people who are different, and I think that’s something we as a community need to continue to work towards.”

Carroll said while accessibility is always going to be a concern for “any blind student” applying to college, he chose NU because of its strong journalism and music programs. He said while he had some annoyances with professors during his freshman year, his process of receiving accommodations — including having his textbooks translated into electronic form and having extended time on tests — was smooth.

He said AccessibleNU was “an advocate” for him, and that he felt supported during his four years here. He worked in the office his senior year while it was looking to hire a full-time assistant technology coordinator.

“Any Northwestern accessibility issue (students have) isn’t because of negligence because of AccessibleNU,” Carroll said. “It’s because people haven’t listened to AccessibleNU.”

He said disabilities services like AccessibleNU are “chronically underfunded” and that the office could better serve students if it had a larger budget and staff.

Dean of students Todd Adams told The Daily in an email that the University is currently considering adding staff to AccessibleNU to help better support students and faculty.

Among the recommendations from the January report was the creation of a web information and digital technology accessibility coordinator position. The person filling the new role, if implemented, would provide training on creating accessible websites. The new hire would also be responsible for working with a service to caption audiovisual materials used in classrooms.

Carroll added that it is the University’s job to give students not only a good education, but a sense of inclusion.

Northwestern’s culture of competition has negatively impacted the way students and administrators think about students with disabilities, Carroll said.

“For better or for worse, the people who come out of these situations are the ones who are shaping the world, and if they’re not accustomed to a culture of inclusiveness, the same bulls–t continues that’s been continuing forever,” he said.

Unaccommodated

Still, not all students with disabilities have a transition as smooth as Carroll’s.

In August 2017, a former Northwestern student filed a lawsuit against the University alleging administrators did not adequately respond to her accommodation requests.

According to the lawsuit, the student — who was pursuing a graduate degree in speech, language and learning — fell on campus in January 2015 and suffered a brain injury that exacerbated a preexisting vision disability. She was concussed and diagnosed with significant regular astigmatism and light sensitivity, the suit alleged. She also suffered from nausea and visual fatigue, and had trouble with visual tracking and reading text and charts.

The student could not be reached for comment, and her lawyers said they could not comment on the case. In a joint motion to the court in November 2017, the parties said they “seek to settle the case” and believed it would be resolved. The suit was dismissed the following month.

The student communicated with the AccessibleNU office and requested accommodations including enlarged course and testing materials, PDFs of these materials in advance and additional time to complete visual tasks, according to the lawsuit.

She took a medical leave for the remainder of Winter Quarter 2015, according to the suit. The student submitted an accommodation request to her program director before resuming coursework in the spring. Later in the quarter, she also received a letter from a doctor explaining her needs and recommending accommodations, the suit alleged.

According to the suit, the student requested course materials but “often settled” for receiving PDF copies in advance to enlarge at her own expense. The suit also claimed Northwestern frequently failed to provide necessary documents in a “timely and workable format.”

The suit alleged that rather than providing accommodations, the University “pressured” the student to discontinue her studies. The University said her involvement in procuring accomodations was not “proactive” and denied that AccessibleNU failed to provide reasonable accomodations.

May said she could not comment on the lawsuit due to student confidentiality.

The student took additional medical leave and returned for Winter Quarter 2016, when she submitted further requests with a second doctor’s recommendations, according to the suit. With accommodations, she completed the quarter.

Complications continued into the start of Spring Quarter, when she completed her first clinical evaluation without the enlarged manuals and protocols that her lawyers alleged she had previously requested. The suit alleged that she received a portable magnifier after contacting AccessibleNU — but when she realized it was not compatible with her Mac and requested more time for the evaluation, her request was denied.

After proceeding with the evaluation regardless, the student was told a week later that it “did not go well.” The suit alleged that “NU absolved itself of responsibility” and “unfairly placed blame” on her.

The University said in its response that the magnifier was “inoperative,” but that it would have worked had the student accepted AccessibleNU’s offer of a compatible computer. NU said it did not fail to provide the student with “reasonable accommodations” and denied that it absolved itself and placed blame on her.

Afterward, the student’s program supervisors “usually” provided materials in advance, but she was given limited time to enlarge them and prepare for clinical evaluations, according to the lawsuit. The suit further alleged that the student felt stress, pressure and anxiety and was “not performing well” by the middle of Spring Quarter 2016.

In its response, NU said it did not “willfully” discriminate against the student and that it did not violate any federal or state statute, regulation or common law.

NU’s lawyers also wrote that the student’s alleged injuries and damages were “caused by her own actions,” and that the University’s actions toward the student were made “for legitimate, non-pretextual or academic reasons.”

According to the lawsuit, the student left Northwestern before the end of Spring Quarter 2016, with $80,000 in student loan debt and no graduate degree.

Providing accessibility

To better address the needs of students, the AccessibleNU office has developed over the years and most recently added a technology coordinator.

In Fall Quarter 2013, AccessibleNU received funds from the University and added an assistive technology assistant director position to its office, who joined staff the following quarter. The added position brought the total number of staffers up to 5.5 — four full-time workers in Evanston and 1.5 in Chicago, May said.

A year after that staffer’s departure, Jim Stachowiak joined the office in the upgraded role of director of assistive technology and assistant director in April 2016.

In 2017, May said, her office received a technology grant from the University that allowed AccessibleNU to buy smart pens — which record speech as one writes — and other innovations.

May said the most common types of accomodations the office gives are time-and-a-half on tests and support for note taking. For technology accomodations, the most common is text-to-speech reading software, Stachowiak said. He added that the second-most common type of accommodation is note-taking tools, including smart pens.

He said AccessibleNU also provides FM devices to students with hearing disabilities, as well as access to captioning. For students who need textbooks with enlarged print, the office usually sends the student a PDF that can be enlarged online, Stachowiak said.

“We’re very student-driven, so should we sit down in an intake and a student indicates to us that they would need something … we’d get it and loan it out to them for the duration of their time,” Stachowiak said.

To ensure that technology is equally accessible, the January report recommended a campus-wide website accessibility assessment that would evaluate the University’s websites and web-based services, as well as its hardware. The report also recommended that schools keep accessibility in mind when purchasing software.

The report suggested the University fund a mobility transport service used by students, faculty and staff with both temporary and permanent disabilities. Peer institutions, such as the University of Chicago and the University of Michigan, already offer comparable systems.

Stachowiak added that taking advantage of technology — like cutting down a student’s reading time from five hours to an hour — helps “level the playing field” for students with disabilities.

“For people without disabilities, technology makes things easy,” Stachowiak said. “For people with disabilities, technology makes things possible.”

Contrasting campuses

Hassan, the NU-Q Communication senior who studied on the Evanston campus for three quarters last year, received a smart pen, along with other accommodations.

Still, Hassan, who is legally blind and has trouble seeing details in the distance and reading texts up-close, said his biggest challenge was adjusting to the Evanston campus’ layout.

“The issue was mainly adapting to the actual campus in terms of physicality, at least for the first two weeks (before) you get used to it,” Hassan said. “It was majorly difficult to navigate, especially with all the construction around.”

He said another problem for him was a lack of signage, or signs that were hard to read because the text on them was too small.

Hassan said he emailed AccessibleNU after having trouble navigating campus. A representative from the office responded to him the same day, saying he would look into available services, Hassan said.

Several days later, AccessibleNU said though they could not provide him a tour, Hassan could hire someone from a Chicago company, which charged by the hour, Hassan said. He added that it was “way out of” his student budget, so he did not opt for an orientation.

Hassan said spending time on the Evanston campus helped him “get the hang of” its layout and he managed to get used to it without the orientation guide.

May said she could not comment on Hassan’s case because of student confidentiality, but said that American students can usually receive an orientation through state programs that may not be available to non-citizens.This option did not apply to Hassan, who is a Lebanese citizen.

Overall, though, Hassan said AccessibleNU helped him adjust to Evanston.

Hassan said he received extra time on exams, and was allowed to be late or miss class because of medical reasons.

He said his professors in Evanston were helpful in sharing handouts with him as PDFs, and that some who don’t normally share presentation slides would email them to him.

Generally speaking, he said NU-Q’s campus, which opened in 2008, is easier to navigate because it was conceived with accessibility in mind. The NU-Q campus only has one building, while the Evanston campus has many buildings spread throughout a much larger area.

Students with vision disabilities like Hassan face challenges that many other students don’t even think about. At both NU-Q and the Evanston campus, for example, there are monocolored staircases that lack any sort of visual markers. This makes it difficult for visually impaired students to tell where stairs begin and end, as well as where possible landings might be, Hassan said.

The January report provided recommendations for bettering the campus experiences of students with disabilities. It recommended the University complete a campus-wide accessibility assessment, which began last spring.

Still, Hassan said as a whole, AccessibleNU did a good job making him feel welcome.

“Honestly, overall, I never thought of things other than the orientation that I wish I could’ve had,” Hassan said.

He added that because the office has worked with people with similar disabilities before, it makes it easier for students to receive help. The office also makes sure that everyone has an equal opportunity to succeed regardless of one’s disability, he said.

“It’s just making sure that everyone is at the same playing field with everyone else just to be able to make the process as fair as possible,” Hassan said. “If it weren’t for AccessibleNU or AccessibleNU-Q, I don’t know what I would’ve done for the past four years.”

Seeking community

Though AccessibleNU works to ensure students with disabilities receive necessary accommodations, there are no student organizations dedicated solely to “advocating for” students with disabilities, said Ingerman, the ASG project lead.

Ingerman tried to change this her freshman year. After talking with Scott Gerson (SESP ’17), the two decided to start Beyond Compliance, an unofficial group for students with disabilities to create a support network and sense of community.

The organization held meetings, hosted student panels, put on benefit concerts for AccessibleNU and advised Dance Marathon on how to use more inclusive language. The group, however, had attendance issues, and Ingerman said it was difficult to maintain, given that Gerson graduated in fall 2017.

She said many of the initiatives Beyond Compliance started have since been tackled and researched by members of ASG’s accessibility and inclusion committee, and that the committee has much more time and resources to dedicate to these initiatives.

Ingerman said she is working on creating a disability workshop to train student groups. The workshop would teach students who work with people with disabilities how to practice sensitivity and use appropriate language, she said.

She added that the group has also started to address medical leave of absence policies and temporary disabilities.

The committee is also planning on creating a CTEC-like review of NU professors with regard to accessibility. She said while some professors, for example, are willing to share their presentation slides with students, others aren’t. This proposed system, she said, would allow for students to have more control from the start in crafting a schedule that meets their particular needs.

“It’s the on-the-ground accommodations that make Northwestern accessible or non-accessible,” Ingerman said. “This would be a really great way for students with disabilities … (to) have more knowledge about the professors that they’re planning to take classes with on the front end.”

Ingerman said many NU students often don’t focus on accessibility concerns.

“It’s not a priority for people, but I think it really should be because people who get into Northwestern are clearly able and capable of being a full member of this community,” Ingerman said. “To diminish their value by not supporting them is really dangerous and harmful to them and to our community in general.”

She added that though AccessibleNU can often receive the blame for not doing enough, Ingerman said this isn’t necessarily true, noting the University will never be 100 percent accessible.

Ingerman said, for example, paths aren’t always cleared of snow first thing in the morning. In conditions like this, she said that AccessibleNU can only do so much to support students, but that the staff does a “really fantastic job.”

Still, she added the office — with its limited staff and large number of students it supports — could do better with more University funding, and if professors were required to have training on supporting students with disabilities.

Mulukutla, the ASG president, said NU should provide all students with an education, not just those who are able-bodied or neurotypical and may not have to think about accessibility concerns on a daily basis.

“This campus exists to serve students and empower them to be the best versions of themselves,” Mulukutla said. “How can it do that if students aren’t able to access the resources, the learning, the education, the experiences?”

Carroll said though there remains work to be done, the University has become more accessible over time.

“We’re finally confronting some of the stuff that’s bubbled up over hundreds of years,” Carroll said. “The cat’s out of the bag now.”

Email: jacobholland2020@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @jakeholland97