In Focus: Student-athletes face unique mental health challenges, work to overcome stigma of getting help

March 7, 2018

At the Northwestern women’s basketball game against Indiana on Jan. 14, 2017, Amber Jamison didn’t wear her regular jersey. Instead, she wore No. 5 in honor of Jordan Hankins, her best friend on the team. Just five days earlier, Hankins had died by suicide.

Jamison scored 13 points that afternoon, helping lead the Wildcats to a win. Three days later, she put up a career-high 22 points to take down Michigan State.

Off the court, however, it was a different story. Jamison was struggling to cope with Hankins’ death, which hit her even harder at the end of the season.

“I couldn’t push everything that had happened to the side and act like it didn’t happen,” Jamison said. “I had to confront it at some time.”

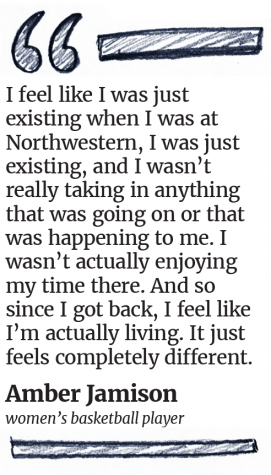

That time came in November, when Jamison decided to take a leave of absence for Winter Quarter and redshirt for the 2017-18 basketball season.

Amber Jamison

Many student-athletes at Northwestern deal with a myriad of challenges, including injuries, academic struggles and the pressure to live up to expectations of a healthy body image. But an often-unspoken challenge, both at Northwestern and nationally, is coping with mental health issues.

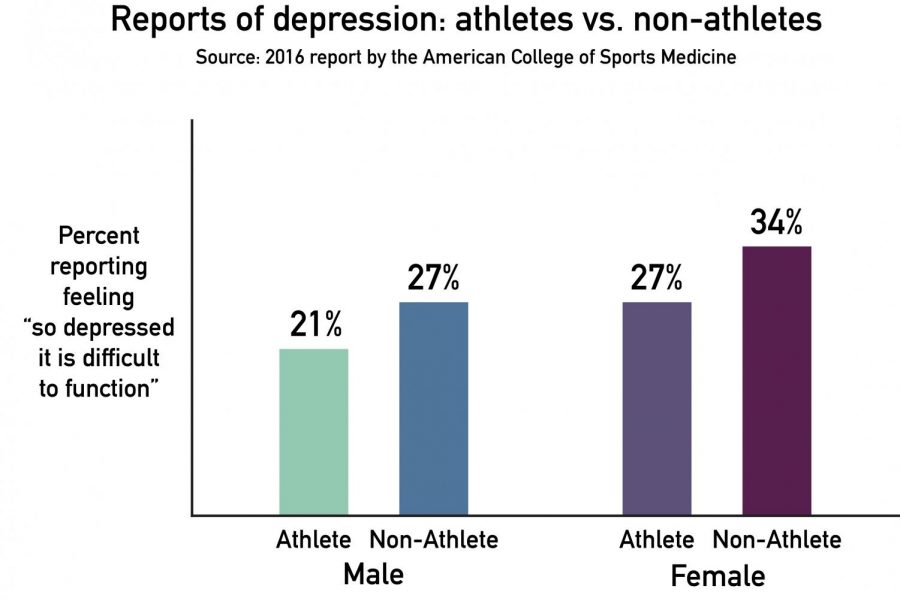

According to a 2015 NCAA survey, about 30 percent of student-athletes self-reported that they have been “intractably overwhelmed during the past month.” The survey also found that nearly 25 percent of student-athletes reported being exhausted “from the mental demands of their sport.” Meanwhile, a 2014 NCAA report found that student-athletes are less likely to report issues with depression and anxiety than their non-athlete peers.

Jamison said she feels athletes at Northwestern are, “for the most part,” on their own, although the athletic department does make resources available to them.

“They make sure that student-athletes know that we have resources on campus,” she said. “But I just think there’s a bad stigma around mental health. And people think that if they go to (Counseling and Psychological Services) they’ll be labeled a certain type of way.”

Facing the stigma

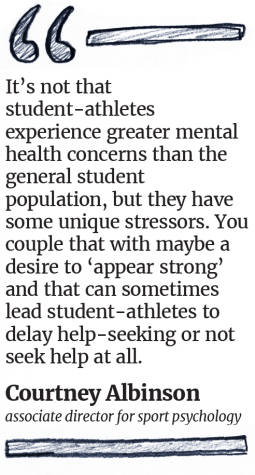

CAPS staffers are working to change that label, said Courtney Albinson, associate director of sport psychology.

Albinson said CAPS works with athletic teams upon request and that student-athletes can make individual appointments with sport psychologists to discuss anything from mental health issues to performance improvement. She said that includes consulting with coaches on how to provide support and recommendations for athletes.

These services, however, are fairly new. Although the University shifted to an athlete-specific model of care in 2013, she said, CAPS formally developed a sport psychology unit in fall 2016.

While the staff does its best to mitigate the stigma, Albinson said she recognizes the reasons student-athletes may decide not to visit CAPS. She said there are certain cultural factors in sports that make it harder for student-athletes to seek help. Albinson also noted student-athletes face “unique stressors” when it comes to their mental health.

“You couple that with maybe a desire to ‘appear strong’ and that can sometimes lead student-athletes to delay help-seeking or not seek help at all,” she said.

Jamison said she dealt with a variety of external factors when deciding to seek counseling at CAPS. The negative perception of using counseling services, she said, still surrounds those grappling with mental health issues in some communities.

“For me, it had a lot to do with my culture. In the black community, it’s just a bad stigma around mental health,” Jamison said.

Jamison said she knows people whose parents perceive mental health from a negative spiritual perspective, or don’t believe in mental health problems altogether. Though it was difficult to tell her parents about her struggles, she said they were supportive, and she began seeing a psychologist at CAPS who informed her about the possibility of taking a medical leave.

She said she was concerned about blindsiding her teammates with the decision. One week before the deadline, she got the request approved by her coaches and filled out the paperwork the same day.

After sitting out the team’s first game, a win over Chicago State, Jamison told the team she would be missing the rest of the season.

“It was tough because I tend to — I think everybody does this, try to hide their feelings,” Jamison said. “I know they felt kind of hurt that they didn’t know what I was going through, and then it was kind of like I told them and then I left.”

Following the NCAA’s Best Practices

Thirty-five percent of the student-athlete population at Northwestern visited CAPS between July 2016 and June 2017, according to the CAPS annual report.

Albinson said many of the efforts to help student-athletes during those visits were guided by the NCAA’s Mental Health Best Practices, a list of recommendations designed for universities to follow when dealing with athletes’ mental health. She said having two sport psychologists on staff helps meet these guidelines.

In March 2016, the NCAA approved a $200 million fund to be distributed to Division I universities that “must be used explicitly for programs that benefit student-athletes.” It added that the funds are specifically earmarked to support academic resources and students’ mental health.

Dr. Jeffrey Mjaanes, the University’s head team physician, told The Daily in an email regarding the fund that the University “will be receiving some of that money” and using it according to NCAA guidelines. However, he said administrators don’t yet have specifics on how it will be used.

Mjaanes said student-athletes sometimes don’t realize their problems may be mental health-related.

“They might come in and say, ‘I’m not sleeping well,’” Mjaanes said. “I find out that I think they’re not sleeping well because of anxiety or depression. Sometimes a visit that doesn’t seem like a mental health visit will be turned into a mental health visit.”

Support systems for student-athletes take many forms across the country. While a 2016 survey found that 72 percent of Division I universities offer counseling services to student-athletes in centers similar to CAPS, only 20.5 percent had “a mental health provider who worked in the athletic training room.”

Northwestern does not have a licensed mental health provider in the training room, but Mjaanes said there are various ways a student-athlete can enter the support system at Northwestern, whether that means meeting with him, a team trainer or a CAPS psychologist.

“A lot of them probably end up having stress. We see a slight increase in the utilization of these services by student-athletes precisely for that reason,” Mjaanes said.

Confronting body image expectations

SESP senior Leigh Healey, a bodybuilder and Northwestern cheerleader, has never been a student-athlete in the traditional sense. Healey, who writes a blog on fitness and mental health, said she has faced pressure to maintain a certain body image.

“People in all my circles knew me as the girl who did these ‘fit things.’ I just saw this as a new identity I had to form,” Healey said. “I felt so much like other people saw me as this person that I thought I no longer was. … I was like, ‘Well, I really want to eat five cookies in a sitting,’ and I felt like other people were like, ‘Wait, Leigh doesn’t do that because she’s a bodybuilder.’”

Leigh Healey

Student-athletes are affected by eating disorders at a higher rate than the general student population, according to a 2016 report by the American College of Sports Medicine.

The report also found that 18 to 20 percent of “elite female athletes” met criteria for eating disorders, while only 5 to 9 percent of a female control group met the same criteria. The report noted this is not a gender-specific issue, as eating disorders among male athletes are also increasing.

Healey achieved early success in bodybuilding, winning her first competition and earning a spot in a national contest in 2017. That success, however, had negative consequences for her physical and mental health, she said. She added that bodybuilding perpetuated her eating disorder and body dysmorphia, allowing her to justify her means to get lean for competitions.

After finishing her first show, Healey said she felt a lot of pressure from people who asked her if she would compete again.

“I remember being on the phone with my dad, being like, ‘Oh my god, I can’t do this, but I want to do it, but I can’t, but I qualified for Nationals so I have to go, but I don’t want to go at all,’” she said.

The transformative experience for Healey came when her friends mentioned how visiting a therapist helped them. For Healey, it normalized the idea of seeing one herself, and she decided to try it.

Albinson said the staff at CAPS coordinates with the athletic department to help athletes deal with outside pressures to maintain a certain body image. Throughout the year, CAPS hosts outreach programs for student-athletes to discuss stress management and maintaining a healthy body image, Albinson said.

“We work so closely with sports medicine staff and even coaches and other athletic staff who are in a position to recognize when a student-athlete could benefit from our services and additional support,” Albinson said. “It’s normalizing help-seeking for athletes.”

For Healey, the key was finding the right person to talk to. She said she initially struggled due to the personal nature of the conversations, saying she wasn’t “in love” with the therapists she saw in Evanston.

After learning about CAPS, but not clicking with the therapist during her first session, Healey said it “was really easy to keep giving up.” Now, however, Healey said she meets with a sport psychologist at CAPS once a week.

Healey said the sessions have helped her gain perspective.

“Looking back on it now, people obviously didn’t realize how much work went into it, and how tired and how drained and how exhausted I was from it … and how you feel at the end of it, like you feeling like a walking zombie,” Healey said.

Balancing school and sports

Caleigh Ryan

Northwestern student-athletes graduate at the second-highest rate in the country among top-tier athletic schools, according to Northwestern Athletics. The Wildcats boast a graduation rate of 97 percent, the highest in the Big Ten.

But balancing academics and athletics adds “a lot of mental pressure,” Brandon Medina (Weinberg ’17), a former soccer player, said.

“You can’t show up to class … not prepared for the test or not prepared with your homework and say, ‘Oh, I couldn’t do it because I had practice,’” he said. “And you can’t show up to practice, you know, very lazy or say you’re tired because you were up all night studying for tests.”

Academic distress is the second-most self-reported concern among undergraduates visiting CAPS. To help balance classwork with athletics, Northwestern student-athletes are paired with an academic adviser who meets with them weekly during their freshman year. The same adviser continues to work with the students all four years, meeting with them quarterly to help plan schedules and connect them with tutors for classes.

Caleigh Ryan (Medill ’17), a former volleyball player, compared being a student-athlete to working a full-time job on top of being a full-time student. She said being an athlete at Northwestern is a “blessing and a curse.”

“You want to compete in the best conference in the nation,” she said. “You want to have a great academic school. You want that challenge.”

For former swimmer Lauren Abruzzo (Weinberg ’17), being a student-athlete was a similarly double-edged sword.

Abruzzo found that daily practices and training actually helped her relax, but the neverending commitments of school and swimming prevented her from focusing on her own mental health.

“Even though on a day-to-day basis swimming was therapeutic for me and also helped me decrease my daily stress, I think it also exacerbated some of my mental health problems,” Abruzzo said. “Because I was training so much, it gave me less time to think about my mental health and to go to therapy.”

University staff occasionally steps in to help athletes who are struggling academically. For Jamison, the basketball player, this academic counseling helped but also added another thing to the pile of work.

“Our athletic department does a lot to make sure we’re staying on top of our classes,” she said. “If they notice that you’re struggling with maintaining a schedule or just struggling with school in general … then they’ll meet with you on a weekly basis. … But sometimes that can be stressful, just trying to fit the meeting in your schedule.”

Dealing with physical and mental injuries

Though some athletes take time off on their own terms, others are forced to by injuries.

Medina, the former soccer player, tore his ACL twice during his time at Northwestern. The experience was brutal, he said. Being away from the team — and the game — for months can have an effect on an athlete’s mental health, he added.

Taking a leave, he said, means going from “doing the thing you love most to not being able to move.”

Brandon Medina

“You can’t focus in class, you don’t sleep well,” he said. “But you’ve got to keep moving on, you’ve got to accept it for what it is and say, ‘Alright, now I’ve got to go to rehab, got to go to class,’ and just set yourself small goals here and there.”

The recovery process wasn’t easy, Medina said, but it led him to be more aware of his own mental health. Northwestern matched him with a sport psychologist at CAPS. Medina said he initially thought it was “a bit unecessary” but found the meeting to be helpful.

Albinson said CAPS can support injured student-athletes in various ways, including a resilience and recovery program in partnership with sports medicine staff to help student-athletes deal with returning after an injury.

“(We) know that it can be really helpful to talk about recovery from injury … and even some of the mental skills that can be helpful not only during recovery, but also during times where you can’t be actively out there on the field or the court,” she said.

After dealing with his own injuries, Medina said he tried to help a younger teammate who was going through the same thing.

During Medina’s junior year, a freshman on the team also tore his ACL. Medina said he spoke with the teammate about the recovery process and provided support as a way to “pay it forward.” Few people had seen the freshman play before he got injured, he noted.

“No one really knew him,” Medina said. “You kind of have to put yourself in someone else’s shoes and help them as much as you can.”

Building communities

Student-athletes at Northwestern have their own communities to help each other deal with the unique issues they face.

Student-athletes at Northwestern have their own communities to help each other deal with the unique issues they face.

Abruzzo, the former swimmer, said there are three main groups: Engage, the Student-Athlete Advisory Committee and Peers Urging Responsible Practices through Leadership and Education, an athlete support group.

The advisory committee organizes events and communicates with administrators about issues related to student-athletes. Engage plays a similar role, but with a focus on sustained dialogues on subjects such as race, sexuality, gender and economic background.

Meanwhile, the P.U.R.P.L.E. peer mentorship program focuses on the mental health of student-athletes, encouraging those dealing with mental health issues to talk with someone and sometimes stepping into that role themselves.

Ryan, who was one of the mentors working with the volleyball team, said P.U.R.P.L.E. is one of the best resources offered by Northwestern Athletics.

“I want there to be two or three people on every sports team who care about this as passionately as I do and are able to look out for people who misperceive that mental illness is a weakness or that it’s something to be ashamed of, because it’s absolutely not,” Ryan said.

P.U.R.P.L.E. has an executive board that oversees the various mentors on the individual teams, said board member and senior fencer Emine Yücel.

Part of the board’s job is to give mentors the tools to help teammates not directly involved in P.U.R.P.L.E. and to set the agenda for the group’s meetings. This year, Yücel said the focus is on mental health.

“It’s a great group of people and very, very important,” Yücel said. “The athletic community and everyone who works at athletics really helps us with it because they understand the importance of it.”

Medina said that in the end, the best support system athletes have is their teams.

“Your teammates are much more than friends,” Medina said. “For one, they try to be as supportive as possible. On the soccer team we all lived together, so that is very helpful, just telling each other, ‘Come on, it’s alright, you’ll get through it.’”

Taking a step away

This season, as the women’s basketball team struggled throughout conference play, Jamison said she was tempted to offer advice and encouragement to her teammates.

The team tallied only four Big Ten wins and lost in the second round of the Big Ten Tournament, but Jamison said she held herself back from reaching out.

“I know how I get when we’re going through tough times, and if we lose a game, or even if we win a game, sometimes I don’t want to talk to people,” Jamison said. “After games I always want to call them. But then I stop myself because I’m like, ‘Well, maybe I should just let them breathe and wind down from a game.’”

Jamison said she was “not in a good place mentally” the past two quarters. While she does not have to return for Spring Quarter, she said she intends to be back.

Her leave of absence allowed her to relax by taking a break from the stress of waking up at 5:30 a.m. and going to bed at 3 a.m., she said.

“I feel like I was just existing when I was at Northwestern. I was just existing, and I wasn’t really taking in anything that was going on or that was happening to me,” Jamison said. “I wasn’t actually enjoying my time there. And so since I got back (home), I feel like I’m actually living. It just feels completely different.”

Despite the availability of student support groups and psychological services, Jamison said the best way for her to improve her mental health was to step away and focus on herself.

“At first, I thought that I would have to do that on my own and just figure it out and that I would have to keep hiding how I was feeling instead of talking to someone about it,” Jamison said. “Taking this time off was really good for me because I could figure out how to cope without all the stresses of being a student-athlete.”

This article is been updated to clarify Lauren Abruzzo’s experiences and her thoughts on student-athlete mental health.

Email: josephwilkinson2019@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @joe_f_wilkinson