In Focus: Under proposed housing plan, Northwestern’s residential life faces uncertain future

February 19, 2018

When picking a college, Scarlett Machson wasn’t sure Northwestern was the right fit for her.

Though her mother was pushing her to apply to NU, Machson said she wasn’t excited about the prospect of becoming a Wildcat. But then she discovered the Communications Residential College.

After scrolling through CRC’s website, Machson realized she shared interests with the residents and could find a community there. She then pulled up the Common Application and selected NU as her Early Decision school.

“I applied to Northwestern for CRC, there’s no question about it,” the Communication sophomore said.

CRC is one of 10 residential colleges currently operating within the University’s housing system. Other housing options on campus include residential halls, residential communities and Greek houses.

Today’s system, however, is on track for an overhaul: A University report released in January details plans to implement a single residential model and “universalize” the undergraduate housing experience. The Undergraduate Residential Experience Committee’s report recommends eliminating residential colleges, incorporating Greek housing into the larger residential system and changing the way students choose housing.

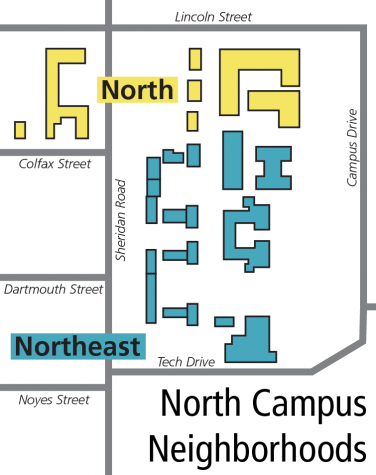

The proposed framework consists of five “neighborhoods,” a model that aims to create stronger communities by fostering engagement and inclusion, vice president for student affairs Patricia Telles-Irvin told The Daily in October. The report touts the proposed residential experience as “the only universal undergraduate experience outside of the brief window of Wildcat Welcome.”

Administrators said students may begin to see major changes in fall 2019 at the earliest. Aside from small adjustments, the current housing selection process will remain the same for incoming students in fall 2018, said executive director of Residential Services Jennifer Luttig-Komrosky.

The recommendations, along with the implementation of a two-year live-in requirement this past fall, could significantly change students’ residential experiences. Although administrators say the plan would promote inclusion within on-campus housing, some students are worried the changes will replace elements of the current system that effectively create communities.

For Bienen and Communication freshman Valérie Filloux, being accepted to live in Chapin Hall, the humanities residential college, was “a dream come true.”

Following the report’s release, Filloux and other students have voiced concerns with the recommendations’ potential to limit their housing options by removing residential colleges and changing the housing selection process.

“When I found out, me and a couple of friends, we were just heartbroken,” Filloux said. “We had just entered into this amazing community and we found our home and we were feeling welcomed and accepted … and just to be told that the entirety of its future is in complete flux is really heartbreaking.”

Time for change

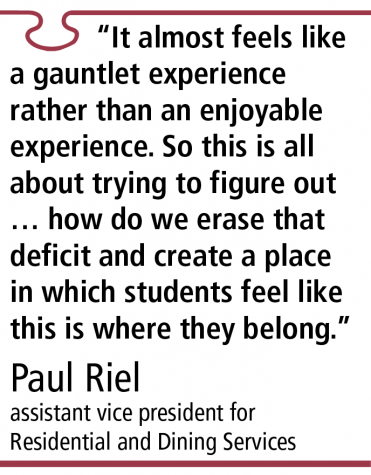

By reassessing the housing model, administrators hope to improve students’ overall experience, said Paul Riel, assistant vice president for Residential and Dining Services and co-chair of the Undergraduate Residential Experience Committee.

“(NU) almost feels like a gauntlet experience rather than an enjoyable experience,” Riel said. “So this is all about trying to figure out … how do we erase that deficit and create a place in which students feel like this is where they belong.”

According to the report, the proposed framework would have houses of about 75 to 150 students within the wider neighborhoods of 700 to 1,100 students. Smaller existing buildings would stand alone, while some larger buildings may be divided into two or more houses.

Within neighborhoods, students would have access to collaborative and educational spaces, gyms and other community amenities, Riel said.

Another main goal of the model is to strengthen non-academic relationships between faculty, staff and students, Riel said. Four faculty currently live on campus and preside over residential communities, but he said the goal is to have two live-in faculty per neighborhood, or 10 total.

“We have to just kind of reset and reimagine what the residential experience should look like and work toward that,” Riel said.

Forming neighborhoods

Administrators decided to implement the two-year live-in requirement in an attempt to increase students’ access to academic support and community resources, Riel said.

Starting with the Class of 2021, incoming freshmen have to live on campus for two years. Under the proposed framework, those two years would be spent not only on campus, but within the same neighborhood, Riel said.

While being part of the same community for two years may help with consistency, Weinberg senior Joey Salvo — president of the Residential College Board — said he is concerned students would have limited flexibility to move between neighborhoods.

“It could make people feel a little trapped where they are,” said Salvo, who lives in the Slivka Residential College of Science and Engineering. “There’s no guarantee you’re going to take to whatever community you’re put in.”

To build communities where students feel comfortable, the report recommends changing the housing selection process, like placing students based off an algorithm or their Peer Adviser groups.

This year, incoming students ranked their top five building choices, and those without roommate preferences filled out a lifestyle survey to be matched with someone, Luttig-Komrosky said. Many residential colleges also required supplemental essays, she said.

According to the report, placing students in neighborhoods based on their PA groups could help with Wildcat Welcome activities and keep groups connected throughout students’ first year.

The process would also aim to create a roughly equal distribution of students from different schools across neighborhoods. This would help ensure resources are allocated and used fairly across neighborhoods, said committee member Brad Zakarin, director of Residential Academic Initiatives.

Before administrators consider PA groups, however, Salvo said they should understand why some are more effective than others in fostering strong communities.

“A lot of people that I’ve talked to personally have said they didn’t click with their PA groups in the way that they’d hoped, or at least in the way that they did with people they were living with,” Salvo said.

The algorithm suggested by the report would account for a variety of preferences.

Zakarin said the recommended selection process would allow students to prioritize which characteristics are most important to them in a house — like proximity to a dining hall or available interest groups.

However, some students expressed concerns with the algorithm. CRC president Beth Koehler said she is worried the algorithm may limit student choice.

“It sounds like a vaguely defined algorithm will be taking over a lot of the searching and process that’s trying to find a place where it’s right for you to live,” the Communication sophomore said. “I just don’t know if it would be able to make the right choice for you. I don’t think it can.”

A threat to themes

For residential college students, much of that choice revolves around shared interests, Machson, the CRC resident, said. In her case, she wanted to be surrounded by “creative kids” like herself. Within her first few days on campus, she said she bonded with other CRC students over the famously terrible movie “The Room.”

However, permanent themes for residential colleges — like communications, humanities and public affairs — would be dropped under the proposed model.

Residential colleges were created out of a 1969 report “A Community of Scholars,” which Riel noted allowed the option of ending themed housing if it proved ineffective. Riel said the committee found that the thematic elements of residential colleges are “not as robust” as they once were due to low return rates and intake rates.

Removing themes would be a major blow to residential colleges, Machson said, and would take away much of what draws students to these communities. Though she agreed some themes are less integral, she said for certain residential colleges — particularly CRC, Chapin and Slivka — themes are “vital to (their) existence.”

In place of permanent themes, the committee recommends incorporating temporary groups around common interests.

Rather than being assigned to houses indefinitely, these “interest groups” would be formed based on student demand, Zakarin said at a forum in January. The groups would be voted on every few years so effective themes could persist while others “peter out,” he said.

This model, though, puts the impetus on students — many of whom are already “over-engaged” — to create the groups, said Chapin associate chair Jason Kelly Roberts. Without the stability of themes, students could feel burdened with leading the groups or simply not participate, said Roberts, who also works at the Office of Fellowships.

Filloux, who lives in Chapin, said the process of voting to decide on interest groups could also create tension.

“In a school in which everything feels very competitive, they are making the housing system into something that gives us a lot of choice, but in that choice there is a lack of freedom,” Filloux said. “We come to housing and communities to get away from that (competition).”

Other students are less attached to themes, but are concerned about the ability of houses to form lasting identities.

Willard Residential College co-president Newlin Weatherford, a fifth-year senior in Weinberg and McCormick, cautioned that some of the residential colleges’ individuality could be lost in the process of “universalizing” the residential college experience. Though the flexibility to create new traditions could be beneficial, he said administrators should make sure the new framework doesn’t erase traditions that already exist.

CRC vice president Katie Kearney said her housing experience was impacted most by CRC’s annual Radiothon — a 50-hour radio show fundraiser. The Communication sophomore said she credits the well-established tradition with helping her befriend other CRC residents and fit into the community.

She noted that as long as student governance remains in place for the houses, residents could still be able to pass down themes and traditions each year.

While Salvo, the RCB president, said he is not opposed to changing themes, he noted the details of the proposed alternative remain “hazy.”

“The interest groups are a great idea, but they may seem a little too informal just in their current presentation,” Salvo said. “Especially because a lot of people believe that having a central idea or theme that people can unite around is really critical to building a community.”

A focus on well-being

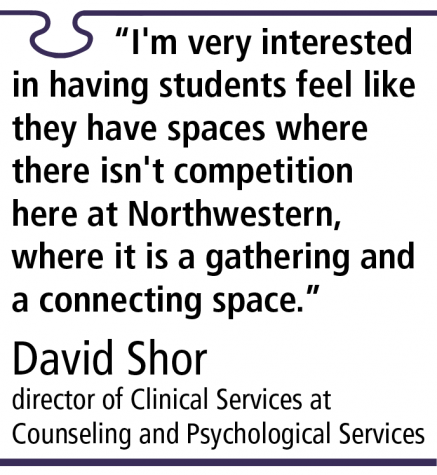

Administrators have also focused the new model on helping improve students’ mental health and reducing the sense of isolation some feel.

Recent housing renovations and upcoming construction plans have emphasized building communities, Riel said.

In January, Willard Hall reopened after more than a year of construction. The renovations include the addition of a fitness center and a classroom that can also function as a theater or catering space.

Foster-Walker Complex, a residential hall with nearly 600 single rooms, looks drastically different than nearby Willard Hall. Foster-Walker has not had major renovations since the 1970s, Riel said, but it is next on administrators’ list.

As it stands, the building’s lounges are “boxy” and not comfortable, Riel said. Weinberg sophomore Grace Wyatt, who lives in Foster-Walker, said the building lacks resources like kitchens and study spaces, and feels “isolating” because there are few opportunities for social engagement.

Foster-Walker has long been criticized. A 1978 PBS documentary titled “College Can Be Killing” asserted the building’s environment heightened feelings of loneliness and depression.

In the documentary, producer Michael Hirsh asks an administrator what parents of students should consider about Foster-Walker.

“We tell them that due to the fact that it has all single rooms … that socialization is difficult,” the administrator responded.

Forty years after the film’s release, Riel said Foster-Walker is still plagued by the same lack of socialization.

“It’s not baked into the environment,” he said. “It was a building that … feels more like you’re warehousing people versus providing community.”

Riel said he would like to allocate money and resources toward creating large community spaces — like putting a roof over Foster-Walker’s open-air courtyards and making room for potential retail, dining or office spaces.

Creating places where students have opportunities to form relationships with their peers in a non-academic setting is essential for mental wellness, said David Shor, director of Clinical Services at Counseling and Psychological Services. Shor, who served on the committee, said the neighborhoods would allow for increased contact between students and faculty or staff who can provide support when needed.

“I’m very interested in having students feel like they have spaces where there isn’t competition here at Northwestern,” Shor said. “Where it is a gathering and a connecting space as opposed to, ‘I’m gonna compete to get into this club, I’m gonna compete to be on this exec board, I’m gonna compete for this grade.’”

According to the report, some of that support would come from “neighborhood liaisons,” which could include graduate and undergraduate students.

Riel said liaisons would be responsible for creating programming relevant to their areas of expertise; for example, a CAPS liaison could lead stress-reduction exercises for students.

The recent report also recommends creating a new staff position to connect students with support systems across campus. Shor said the proposed University Resource Adviser would serve as someone for students to turn to rather than get lost in a “big bureaucracy.”

Riel said the neighborhood structure would encourage residents to pay more attention to each other.

“You come around someone who may be having difficulties, struggling with either a class or something else that’s creating some change, and friends and relationships support that person until they get through that,” he said.

Blurred boundaries

These additional resources would be provided not only to students in traditional campus housing, but also to those living in Greek houses. The report recommends Greek houses be included in the neighborhood framework, giving fraternity and sorority members access to all community amenities.

Currently, the spaces assigned to Panhellenic Association and Interfraternity Council chapters are considered on-campus housing — the University owns the property and loans it to chapters, Riel said. However, he said Greek houses are “virtually independent” and would remain inaccessible to nonresidents under the proposed model.

Because hundreds of students live in Greek houses, Riel said the committee “just couldn’t ignore” that population.

“Our thought process is, if your head hits a pillow on campus, we consider you residential,” Riel said.

Students are able to count living in Greek housing toward the two-year live-in requirement, according to the report.

This could benefit fraternity and sorority membership, said Travis Martin, director of the Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life. Students won’t need to consider having to live on campus an extra year before moving into Greek housing, he said.

By inviting Greek-affiliated students to use neighborhood spaces, Riel said the hope is to encourage more “co-mingling” of students from Greek and non-Greek houses.

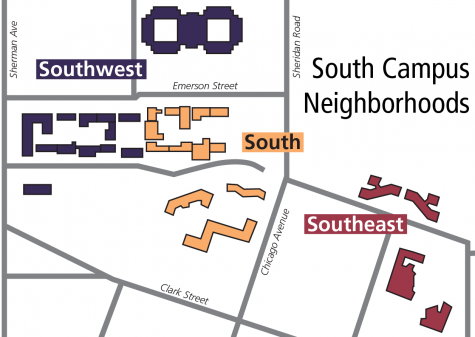

According to the report, Greek houses would be part of all proposed neighborhoods except the southeast area, which consists of CRC, International Studies Residential College, 1835 Hinman, and Jones Fine and Performing Arts Residential College.

Riel said even though Greek housing would be considered part of the residential model, there was no intention, “subtle or otherwise,” to change the organization of the Greek system.

While Greek students would benefit from access to additional amenities, Chi Omega’s PHA delegate Eva Warrender said she noticed some “apparent drawbacks” with the report’s recommendations.

The proposed boundaries would divide sorority houses into two separate neighborhoods, which is counterproductive to PHA’s goal of increasing interactions between different chapters, the Communication sophomore said.

IFC president Jack Harrington said integrating fraternity and sorority houses into neighborhoods “has a lot of moving parts,” adding that the report says many of the proposed changes to Greek communities require further consideration.

This recommended integration has also sparked some concern among non-Greek students.

Weatherford, co-president of Willard Residential College, said part of the motivation for creating the residential college system was to provide social opportunities for students not affiliated with Greek life. But bringing Greek representatives into neighborhood governance could lead to student leadership becoming “Greek-focused,” he said. Under the plan, Willard would be part of the southwest neighborhood, which would also include five PHA houses.

The line between Greek and non-Greek students, though, is already blurry, said Zakarin, who is also a faculty fellow at Willard. He added that there is crossover between residential college students and Greek students, and Greek houses are in such close proximity to other buildings that they are essentially already part of the residential experience.

While Greek students would not have access to CRC, Koehler said she expects there to be a general sense of discomfort among non-Greek students who live in neighborhoods with Greek housing.

“There’s a bad reputation out there for Greek life, and a lot of people hold tightly to that and truly believe it and truly feel uncomfortable around fraternity and sorority culture,” she said.

Harrington said the Greek community and non-Greek community can sometimes be isolated from one another, but hopes the proposed changes work to improve connections between the two groups.

Creating more opportunities for Greek and non-Greek students to mix in informal settings may help alleviate negative perceptions, Warrender said.

“There’s obviously a disconnect between the two, and there’s people that have grievances about it,” she said. “Both people within Greek life and people outside of Greek life have to listen to each other and be interacting with each other.”

Next steps

While students have expressed confusion over the implementation of the report’s recommendations, Telles-Irvin said the University will use working groups to solidify specifics.

As the details are being decided, students said they hope conversations with administrators continue.

Part of the process of drafting the report’s recommendations included efforts to solicit student feedback, Riel said. Committee members held town halls and firesides, and even stopped students in dining halls to discuss their experiences, he said.

Koehler said she felt student opinions were reflected in the report’s recommendations.

“The overwhelming reaction was negative then,” she said, referencing a dinner administrators held last spring for residential college members to discuss the report. “Now it’s certainly not overwhelmingly positive, but there’s a lot of this report that I’m satisfied with and I know that other members of my exec board and my residents are as well.”

Since the report’s release, administrators have hosted two town halls and have collected feedback through online surveys, Zakarin said. Two more forums are planned for this quarter.

However, Filloux, who attended the January meeting, said administrators seemed frustrated that most attendees were from residential colleges and not members of other residential spaces.

“I’m sitting here having the sinking feeling that all we have here are members of residential colleges,” Mary Finn, associate dean for undergraduate academic affairs, said at the January forum. “That everybody here is here really to be an activist for maintaining the residential college system.”

Filloux said the high turnout from residential college members is a result of them feeling uncertain about their living experience, as the information provided to them is “vast and a little confusing.”

“We just want to know what’s going on,” she said. “But I feel like they’re translating that as just plain pushback … while it’s really just we would love to be aware and we’d love to have a dialogue.”

Although administrators’ and students’ visions for improving housing may not align, Salvo, the RCB president, said it is clear that both groups wish to create the best possible residential experience for future students.

In the meantime, Filloux said she already decided she will “most definitely” return to Chapin for her sophomore year.

“Everyone is here to make friends and to form a community,” Filloux said. “It feels like we’ve all kind of joined in to say ‘Yes, we are here, we want to be friends with each other, we want to make this a home.’ Chapin is my home.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @madsburk

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @_allysonchiu