In Focus: As University aims to increase awareness of Title IX process, reporting remains a taxing experience

February 6, 2017

Walking to class on day one of Winter Quarter 2016, Lucy Godinez saw the student who allegedly sexually assaulted her for the first time since leaving his apartment that night.

At first, Godinez said she felt the standard awkwardness of running into a former sexual partner. But as they began making small talk about Winter Break, Godinez said her unease turned into intense discomfort.

It had been nearly seven months since the June night when Godinez said she went home from a party with the male student and had what Godinez later told University investigators was aggressive and non-consensual sex, according to confidential documents obtained by The Daily. She also told investigators that she had been drunk at the time of the encounter and later discovered bruises on the sides of her neck and inside her throat.

The male student declined an interview request after The Daily reached him via social media.

Godinez’s efforts to cope with her alleged assault during those seven months were made easier by the fact that she did not see him, she said. Summer vacation started days after the incident and the student was abroad during Fall Quarter.

Godinez, a Communication junior, said her discomfort seeing the student on the first day of winter classes only intensified as the weeks went on. She started going late to class to avoid the other student, she said, often hiding in the bathroom until she felt certain he had left the building.

Initially, Godinez was hesitant to report the incident. She knew almost nothing about the reporting process, she said. And, since she said she went home with him and did not initially say “no,” she did not think she would have a case.

It was only after another student walked her through Northwestern’s consent policy — one that requires consent to be knowing, active, voluntary, present and ongoing for each part of a sexual encounter — that Godinez said she came to believe the male student had violated it.

Godinez said she did not believe she actively consented to what happened during sex, or the manner in which it proceeded. She told University investigators that she was intoxicated to the point that she could not remember parts of the encounter.

About 11 months after the alleged assault, in early May 2016, Godinez filed a formal report with the Sexual Harassment Prevention Office, also known as the Title IX office. When she did so, she entered a four-month process she described as emotionally trying and invasive.

Godinez’s case was one of 179 sexual misconduct reports the University received during the 2015-16 academic year. The data comes from the Sexual Misconduct Data Report released by the office at the end of 2016.

This past summer, as Godinez awaited the resolution of her case, the University prepared to launch a series of changes aiming to make students more aware of the process and more open to reporting their experiences with sexual assault if they wish to do so.

Reporting the data

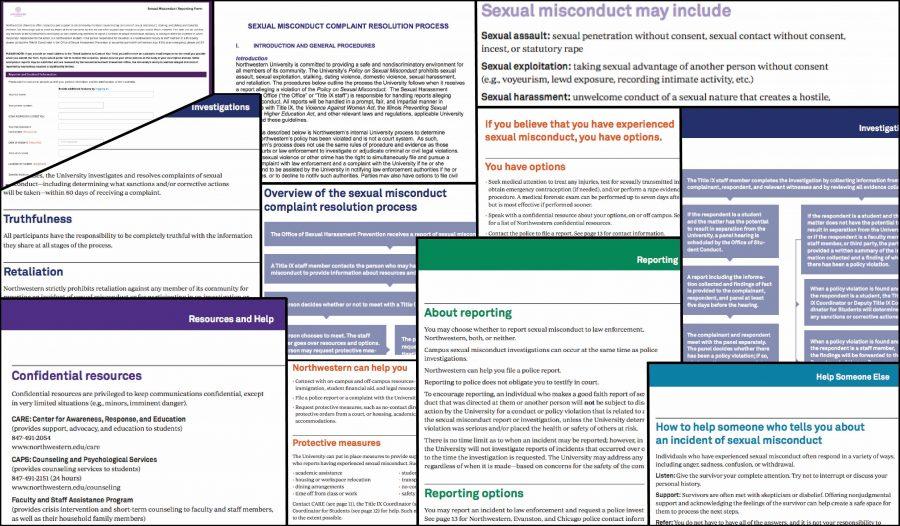

In late December, the Title IX office quietly published its first ever Sexual Misconduct Data Report online. The 11-page document outlines the number of sexual misconduct reports filed during the last academic year, the types of reports filed and their outcomes.

Of the 179 sexual misconduct reports NU received between Sept. 1, 2015, and Aug. 31, 2016, 93 reported sexual harassment and 46 involved sexual assault, according to the data.

Just over half of the reports list an NU faculty member, staff member or student as the respondent — the person who the report is filed against — while the rest were filed against people outside the NU community. The document does not provide details on cases involving people outside Northwestern.

Sixty-five reports were filed against students, according to the data. Sexual harassment and sexual assault constituted the majority of allegations, with 26 and 23 reports filed respectively, according to the data report.

But of the 65 incidents reported, only 26 complainants elected to go through either a formal or informal resolution process. Seventeen incidents, including some reported during the 2015-16 academic year and some cases reported the previous year, were resolved formally in 2015-16.

The respondent was found responsible in 14 formal resolution cases that were resolved during the 2015-16 academic year. Consequences included disciplinary probation, suspension, expulsion and exclusion, which means the student is barred from campus for at least two years.

Graphic by Max Schuman/Daily Senior Staffer

The data calls into question the perception that sexual misconduct and assault “doesn’t happen here,” an attitude that Paul Ang, coordinator of men’s engagement at the Center for Awareness, Response and Education, said he has encountered in his work at NU.

Weinberg senior Molly Benedict, executive director of Sexual Health and Assault Peer Educators, said that without data, rumors about the outcomes of various sexual misconduct cases can influence survivors’ trust in the process.

Peer institutions such as Duke University and Yale University released similar statistics. The Duke Office of Student Conduct received 124 reports of alleged sexual misconduct from May 2015 to May 2016, according to reports released by the university. The Yale Title IX coordinator received 132 reports of sexual misconduct from July 1, 2015 to June 30, 2016, according to documents released by Yale’s provost.

Amanda Odasz, outreach chair of SHAPE and a member of the Campus Coalition on Sexual Violence Student Advisory Board, said she had been asking Joan Slavin, Northwestern’s Title IX coordinator, to release reporting data since last spring.

“That was really important because any university can say, ‘We support survivors,’” Odasz, a Communication senior, said. “But unless you have some numbers to back that up, unless you can actually show that you’ve expelled some people, I don’t know if there’s reason to believe those universities.”

The data report was supposed to come out in Summer 2016 but was delayed due to restructuring in the Title IX office, Slavin said.

Kim Richmond, director of the National Center for Campus Public Safety, said it is misguided to assume that a campus with fewer sexual misconduct reports has less sexual violence.

“In reality, there’s probably just as much sexual violence incidents happening on that campus,” she said. “They just don’t have a process in place that victims feel supported in coming forward.”

Increasing awareness

Godinez struggled for months with the decision over whether to report. Grappling with feelings of doubt and worry, she said she did not think she had a case.

In addition to being unfamiliar with the specifics of NU’s consent policy, Godinez said the only detail she knew was that during the reporting process she would not have to face the other student during a hearing, a change the University implemented in 2014.

NU’s 2015 Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Misconduct demonstrated a lack of awareness of the reporting process, showing that only 36 percent of students surveyed knew where to go to make a report. Just 18 percent agreed or strongly agreed that they understood what happens when a student reports sexual assault or misconduct. The survey, sent to students, had an overall response rate of 15 percent.

The results of the survey were released in September 2015. Three campus groups reviewed the survey results and submitted recommendations to the administration in Winter 2016, according to the Sexual Misconduct Response and Prevention website. The groups found that the data indicated low student awareness about how to make a sexual misconduct complaint as well as low awareness about the complaint resolution process.

On Oct. 6, 2016, Slavin emailed the NU community detailing new resources and changes in the Title IX office, many of which were the direct result of the recommendations.

The email outlined a restructuring of the complaint resolution process: Beginning in Fall 2016, all sexual misconduct complaints would be handled by the Title IX office. Previously, sexual misconduct reports filed by students were handled by the Office of Student Conduct, which disciplines a wide array of student misconduct issues. Slavin said in an email to The Daily that the centralized model is aimed at increasing coordination of prevention and complaint resolution efforts and expediting the University’s response.

The restructuring is a “major” change in the complaint resolution process, Slavin said.

Slavin’s October email also included an updated resource guide and a new educational slide show about NU’s sexual misconduct policies. The definition of consent and the university’s policy on retaliation were also updated, and the university’s Sexual Misconduct website was redesigned. In addition, the Title IX office hired a deputy Title IX coordinator for students, who started in November, Slavin said.

SESP senior Anna DiStefano, co-vice president for student life for Associated Student Government, said she has heard students express confusion about the details of the process and uncertainty about the impact it could have on their lives.

A lack of knowledge concerning misconduct policy and the reporting process can be a significant deterrent to reporting misconduct or assault, said Benedict, the SHAPE executive director. She added that it is important to remember that reporting sexual violence or misconduct is always the choice of the survivor, and that it is crucial to respect the wishes of survivors who don’t wish to report for any reason.

Odasz, the SHAPE outreach chair, said she has generally been pleased with the resources the Title IX office has released, especially the updated resource guide which includes a flow chart of the complaint resolution process.

But even if universities provide ample information about what to do in the event of a sexual assault, students may not have reason to fully absorb the process unless it is necessary, Richmond said.

“A part of the challenge is human nature,” she said. “You can tell me what to do in the event of a sexual assault but until I’m sexually assaulted or someone I know is sexually assaulted, it’s one of the other 100 things I learned during the first week on campus.”

Currently, new students watch a production during Wildcat Welcome that focuses on consent and relationships, said Josh McKenzie, associate director for New Student and Family Programs and director of first-year experience. In 2016, Wildcat Welcome added a second seminar on consent and sexual violence that students participated in about six weeks into Fall Quarter, he said.

McKenzie said Wildcat Welcome does not specifically walk students through the reporting process, but informs students about the NUhelp app, which includes information on sexual misconduct and assists in filing a report.

Step by step

Despite changes to the Title IX structure, the hearing and appeals process remains unchanged. Going forward, it will be the same as the one Godinez went through during Spring and Summer 2016.

Godinez said her second meeting with the Title IX investigator was the most trying. The investigator read over portions of the respondent’s account and gave Godinez a chance to respond to his story, she said. Though she said she understood why this step was important, Godinez found the conversation to be “traumatic.”

“I fell apart,” Godinez said. She said she had to leave, returning about 10 minutes later to complete the interview.

At any point during the Title IX reporting process, the University can implement protective measures, such as a no-contact directive or changes in academic or living arrangements.

In some cases, a third party such as a witness or mandated reporter may report misconduct to the Title IX office. In those cases, the Title IX office emails the individual who experienced alleged misconduct with information about resources and how to get in contact with a Title IX coordinator. The individual can choose whether they want to respond.

Complainants can typically choose whether they wish to pursue an informal or a formal resolution. They can also choose to not follow through with the process. Informal resolutions do not result in sanctions or the determination of responsibility, but could result in further protective measures or an educational meeting for the accused, according to the Sexual Misconduct Report Resolution Process.

The formal resolution process, though, follows a rigid structure: Once the complainant meets with the Title IX coordinator, the respondent is alerted of accusations against them, according to documents describing the process. Both the complainant and the respondent then meet with a Title IX investigator. They have the opportunity to tell what happened, present evidence and give the investigator names of potential witnesses. The investigator then meets with the witnesses.

If appropriate, the investigator may meet with the respondent, complainant or witnesses again. In any case, both the respondent and the complainant are given equal opportunity to respond.

Based on the information presented by the complainant, the respondent and the witnesses, the investigator compiles a report. From there, the case heads to either an administrative resolution or, in cases in which the respondent may be separated from campus, such as Godinez’s, a panel hearing process within the University Hearing and Appeals System.

Before the hearing, the complainant, the respondent and three faculty members who sit on the panel receive a copy of the investigator’s report and conclusion.

Godinez said she was extremely uncomfortable, even “embarrassed,” that the other student was given all the information she disclosed to the investigator.

“Everything that I provided to the investigator went into the report,” Godinez said. “Really personal things … I remember reading the report for the first time and realizing, ‘Oh my God, he’s reading this right now, too.’”

Slavin declined to comment on individual cases due to confidentiality, but said the inclusion of personal information is unavoidable because each party needs to be allowed an “equal opportunity” to respond to the report. Slavin added that personal medical or therapy records can be redacted at the investigator’s discretion.

Per the UHAS guidelines, hearings concerning sexual misconduct are staffed by three trained faculty members. Slavin said the panel members are trained for 12 hours, eight of which are with the Office of Student Conduct. One is with the deputy Title IX coordinator and the remaining three hours are conducted by CARE, she said.

Both the reporter and the respondent appear before the panel, though at separate times, according to documents detailing the process. They give an opening statement, field questions from the panel members and then give a closing statement.

Panel members then review the investigator’s report as well as the information provided during the hearings before voting on the respondent’s culpability and consequences. A letter detailing the resolution is sent simultaneously to each party, and both parties can appeal.

Godinez said that for her, the difficulty of going through the reporting process was exacerbated by the fact that it took longer than she anticipated.

Her reporting process lasted from May 9, 2016 — when she filed the report — to Sept. 20 of that year, when the respondent’s appeal was denied, according to confidential documents obtained by The Daily. This was outside of the 60 days most cases are resolved in, according to the Sexual Misconduct Complaint Resolution Process.

Slavin said though it is the goal of the Title IX office to complete the complaint resolution process in 60 days, a number of factors may cause the process to take longer, such as the number of witnesses who need to be interviewed, the availability of those involved and the complexity of the allegations.

Godinez’s panel hearing was on July 11, 2016, according to the documents.

She did not hear anything about her case until she emailed Tara Sullivan, the assistant dean of students and Title IX deputy director at the time, 10 days later to inquire about the outcome, according to emails obtained by The Daily.

Sullivan declined to comment for this story, citing privacy concerns, and deferred comment to Slavin.

Emails obtained by The Daily show that Sullivan apologized for the delay and told Godinez she could expect her outcome during the first week of August, explaining that the Title IX coordinator was out of the office until then.

Godinez emailed Sullivan again on Aug. 3, writing that the delay had taken a “serious toll” on her mental health. The next day, she received her outcome letter, according to the emails.

Godinez was informed that the panel, supporting the investigator’s findings, concluded that the respondent was responsible for violating three NU policies: sexual penetration without consent, physical abuse, and the use of alcohol, according to confidential documents obtained by The Daily. He was not found responsible for having sex with an incapacitated student, the documents said.

He was excluded.

An excluded student is barred from campus for at least two years and must reapply to the University to return. Seven students were either expelled or excluded during the 2015-16 school year, according to the Sexual Misconduct Data Report.

The case, however, was not finished. Documents show that Godinez and the respondent were given a short window of time to submit a written appeal. Godinez was informed the respondent had submitted an appeal, which argued that the panel made procedural errors, levied an unjust punishment and that the respondent believed Godinez had consented to each sexual activity that occurred, according to documents. Godinez said she submitted a response to his appeal.

The waiting and anticipation was the worst part of the process, she said.

“It was torturous to be told, ‘Oh it’ll come out on this day,’ and then it didn’t,” Godinez said. “I definitely hope that in the future — and maybe it was just my case — but that there is a strict timeline.”

A partner in the process

Overall, Godinez said the process was “long-winded and grueling” but that she would still recommend survivors follow through with a report.

Benedict said the emotional nature of the process can repel people from reporting sexual misconduct. She said it can be especially difficult for victims to keep up with day-to-day life while going through the process.

And LGBTQ students may face even more barriers to disclosing because they may not feel the process speaks to their experience, said Carrie Wachter, coordinator of sexual violence response services and advocacy for CARE, in an email to The Daily.

Richmond said while the nature of a sexual assault investigation is trying for everyone, other resources can help ease the emotional burden.

Godinez started seeing an adviser at CARE shortly before she reported the alleged assault, she said. During the reporting process, Godinez said her adviser’s guidance proved crucial.

“I definitely wouldn’t have been able to do it without the support system I had,” Godinez said. “I don’t think anyone can report and keep themselves safe without having a support system.”

Per the Sexual Misconduct Complaint Resolution Process, both the reporter and respondent may be accompanied by an adviser throughout the investigation. Though the adviser is not allowed to speak or participate in the process, they can offer support.

Before the changes this fall, the Dean of Students office could arrange accommodations for students going through the Title IX resolution process. Mona Dugo, senior associate dean of students, said before the consolidation of the complaint resolution process, her office could coordinate deadline extensions with professors, help with medical leave, rearrange class schedules and give students information about mental health resources. Now, the Title IX office works in conjunction with the Dean of Students office to provide these accommodations, Slavin said.

Regardless of whether a survivor wishes to report or not, Benedict said CARE and the Women’s Center are indispensable resources. But the University discontinued counseling at the Women’s Center this winter, aiming to streamline psychological services at NU.

“The Women’s Center is a great resource, but with counseling being rolled back, I think it’s really problematic,” Benedict said. “Especially because of the way the Women’s Center and CARE work together, because advocacy and counseling are not the same thing.”

The 2015 Campus Climate Survey found that 72 percent of undergraduate females said they would use the Women’s Center as a resource if they were to experience sexual misconduct, while 65 percent said they would go to CARE. Twenty-two percent indicated they would use the Title IX office.

A national conversation

Godinez’s case was decided using the preponderance of the evidence standard, according to documents.

All sexual misconduct cases at NU are decided through this standard, according to the Sexual Conduct Complaint Resolution Process. It is the correct standard of evidence for Title IX cases, as specified in an influential 2011 letter from the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights.

Based on Northwestern’s definition, a preponderance of the evidence means that more than 50 percent of information provided aligns with a finding that misconduct occurred. In court, the standard is used in civil cases, but is considered lower than a criminal trial’s standard of “beyond reasonable doubt.”

Before the OCR letter, some institutions used a “clear and convincing” standard or something similar, which the Department of Education asserts as too high. NU used the preponderance of the evidence standard “well before” the 2011 letter, Slavin said.

The preponderance of the evidence standard has sparked backlash from some universities, professors and students who say the standard of evidence is too low.

Conversations around the preponderance standard even made it into the Trump administration’s cabinet nominee hearings last month. In her hearing, Secretary of Education nominee Betsy DeVos refused to say she would uphold the preponderance of the evidence standard.

Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, an organization that advocates for various rights on colleges campuses, holds that the standard is too low.

Susan Kruth, senior program officer for legal and public advocacy at FIRE, said the organization believes using the preponderance of the evidence standard poses a serious threat to due process rights of the accused.

The Department of Education maintains that the preponderance of the evidence standard ensures equitable treatment of all parties.

From complaint to resolution

Godinez was sitting in class on the first day of last Fall Quarter when she got the email containing the outcome of the appeal, she said.

The respondent’s appeal was denied, and his exclusion was upheld, according to documents.

But for months after, Godinez said she still scanned campus looking for his face.

“My first several weeks here I didn’t want to go outside,” Godinez said. “I remember the first day of classes, and I was walking past The Rock and all these classes were getting out and there was all these people and I couldn’t gauge faces. I knew he wasn’t here but I was still trying to see.”

Godinez said she still talks with her adviser at CARE and has become a vocal advocate for sexual assault survivors, posting about the issue on Facebook and speaking one-on-one with those who have had similar experiences. She said she sees rape culture as a pervasive, campus-wide problem.

“It’s rampant and it’s alive here at Northwestern,” she said.

Email: clairehansen2018@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @clairechansen