Football: Northwestern and Ryan Field’s near-ascendency into college football glory

November 22, 2016

Just over 90 years ago, Northwestern dedicated Dyche Stadium, now known as Ryan Field.

A record 47,000 fans attended the Wildcats’ 38-7 victory over University of Chicago on Nov. 13, 1926, taking in the then-brand new arches, grandstands and towers of Dyche Stadium.

But the finished product they saw was far from what had been imagined just a year or two prior — and from what was supposed to be added in the future.

When the Board of Trustees announced intentions to build the stadium in December 1924, then-University President Walter Dill Scott sought to lay the groundwork for what could have been one of college football’s budding dynasties.

Demand for football was rising in Evanston, a town on its way to becoming the jewel of Chicago suburbs. The team itself was rapidly accumulating talent and not yet hampered by NU’s rigorous academic standards of the 21st century. The collegiate football landscape was evolving on a national scale, shifting away from the Ivy League and westward to the Big Ten and beyond.

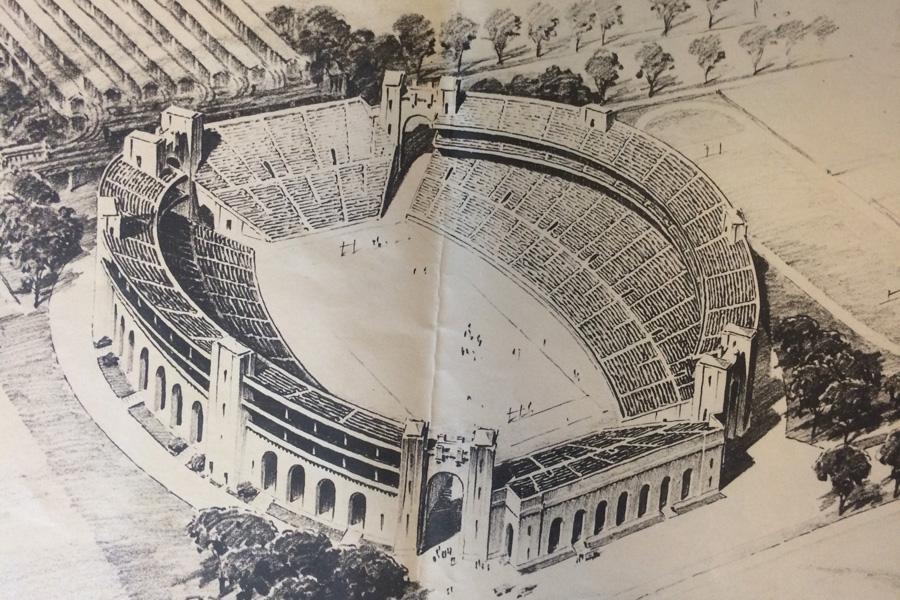

Given those factors, the Board’s announcement sparked a brief period in which the University planned to construct Dyche Stadium into one of the first triple-deck stadiums in the world and one of the largest stadiums of any kind in the United States at the time, with a capacity of 80,000.

Had it happened, the Wildcats — a serious national title contender in 1926, 1930 and 1931 — might have been launched into the premier realm of private university football programs, on par with what Notre Dame and Southern California have become in modern times.

Instead, a combination of rising costs, time constraints and other decisions lost to history significantly downsized Dyche and changed the course of NU football for the nine decades that followed.

Surging support

The Roaring Twenties made a boomtown out of Evanston.

The city population increased by 70 percent from 1920 to 1930, and many of those new residents’ children still enjoyed very realistic chances of attending NU. The University only shifted from first-come, first-serve open admission policies to selective admittance in the mid-1920s and, by the end of the decade, still roughly 40 percent of incoming freshmen did not rank in the top quarter of their high school class.

“It was a very important period in Northwestern’s history,” University archivist Kevin Leonard said. “It was kind of the foundation of the modern university because you have a period of economic prosperity and a visionary, assertive, aggressive (University) president at the same time.”

Scott himself had played football during his time as a student and “knew what an important athletic program could do to elevate recognition of a college or university,” Leonard said.

Around the country, other colleges were rapidly constructing new facilities to house their own growing fan bases. By 1928, for example, fellow private school Stanford was playing in an 89,000-seat stadium and Big Ten rival Michigan had just expanded its structure to more than 85,000 seats.

A proposed mockup of a three-deck Northwestern football stadium. The Wildcats were national title contenders in 1926, 1930 and 1931.

In February 1922, the Alumni News ran a lengthy editorial calling for a similar project at NU, which was playing at that time in a wooden stadium which sat only 10,000.

“If Northwestern put a championship contender or a near contender into the field, the present equipment could not take (care) of half of the people who would flock to see the teams play,” the article said. “Northwestern does not dare to have a winning team until we get a new stadium,” it quoted an unnamed “prominent authority” as saying.

The following years seemed to prove the Alumni News’ assertion correct. NU was forced to host its 1923 game against Illinois at Wrigley Field and their 1924 game against Notre Dame in the newly built Grant Park Stadium — later rededicated as Soldier Field.

Finally, at the trustee dinner of December 1924, the University answered the calls, revealing plans for a new stadium to be built on the same Central Street site as the wooden stadium and designed by architect James Rogers.

Planning stages

Many of the stages of Rogers’ planning have been recorded, usually with sketches or blueprints and more rarely with saved, written letters, in University Archives.

The archives indicate that by Feb. 16, 1925, Rogers had a first blueprint, showing two arc-shaped grandstands on either side of the playing field and “space for standees” behind the endzones.

Rogers quickly expanded upon his rather simple first design. Within the next few weeks, he wrote a letter on behalf of the design team announcing it had added multiple decks to both sides of the stadium — a grander plan that he described as “much more attractive.”

His ideas continued to expand. In a second letter, dated March 5, Rogers wrote of two separate plans — one for “now” and another “for the future.”

The March 5 letter contains the first mention of arched entryways and towers in the corners of the stadium, features that now give Ryan Field perhaps its most distinctive attributes. Due to drainage issues in the ends of Yale’s 60,000-seat stadium, where the entryways were located at midfield, Rogers wanted to avoid a similar problem by placing “very large intakes at the four corners” of NU’s future structure.

The rest of Rogers’ “now” stadium design added onto the Feb. 16 plan by including three decks of seats in separate grandstands along the sidelines.

The “future” stadium plan, moreover, filled in the end zones with even more seats. Rogers wrote that the “size of the ends can be determined from the attendance after we have tried out the original stadium.”

Although no specific estimated seating capacity accompanied the blueprint, it would have been one of the first stadiums in the country to feature three decks — following the world’s first, Yankee Stadium, by only three years.

Yet it wasn’t to be. Ninety years of history have obscured the details of when and why this happened, but later in 1925, the three tiers of seats in the “now” plan were scrapped in favor of a mere two. Nonetheless, the three decks and the filled-in end zones remained a part of the long-term plan.

Instead, the Board approved a plan to build two separate and symmetrical grandstands along either sideline, with two tiers of seats each, arched entryways in all four corners and a press box atop the west side’s second tier. The initial construction would cost an estimated $800,000, but future expansions were anticipated.

Rushed construction

William Dyche, an 1882 NU graduate and the mayor of Evanston from 1895 to 1899, headed the fundraising efforts for the stadium.

“They wanted to get it going in a hurry, so rather than fundraising … they created a bond issue to raise the funds for that,” Leonard said. “Once the university trustees gave the approval to do this, it progressed very rapidly.”

Construction began on May 5, 1926, with the goal of having some sort of playable facility in time for the Oct. 2, 1926, season opener.

That goal failed, and by the start of October, only one deck on the east side was completed, with work continuing on both levels on the west side. Fans attending the season opener against South Dakota were only able to sit on the east side or the middle section of the west side while the unfinished framework lay exposed around them.

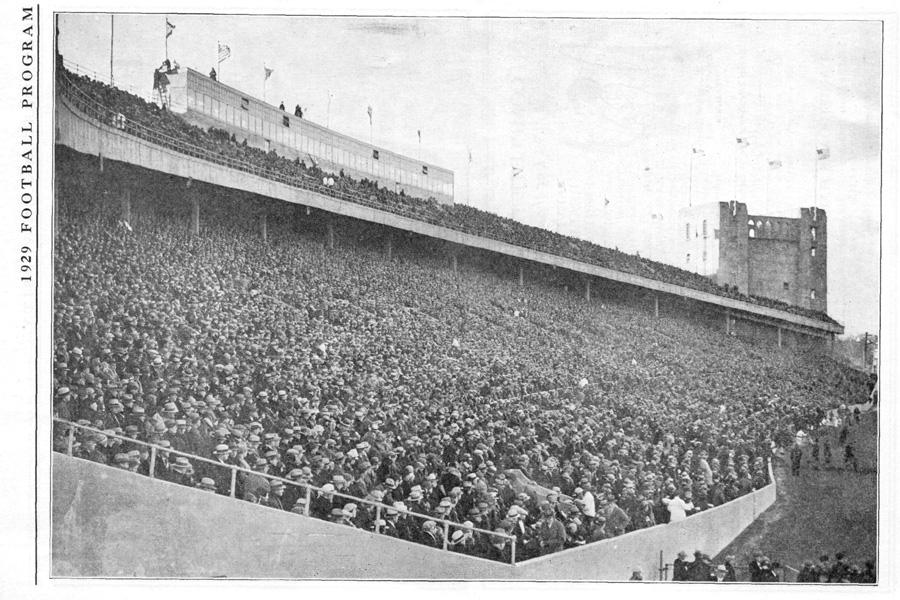

Fans watch a Northwestern football game in the 1920s. The proposed stadium would have seated around 80,000 people.

Nevertheless, the 19,000 who watched NU’s 34-0 victory set a new record for football attendance in Evanston.

Work continued as the season progressed, but at some point, adding the second deck and towers to the east side was postponed for reasons that have since been lost to history. Meanwhile, temporary bleachers were added in the two end zones to meet the ticket demand for in-conference games.

The NU attendance record was continuously broken week by week as more of the stadium was completed: 22,000 watched on Oct. 9; nearly 30,000 watched on Oct. 16; more than 40,000 watched on Oct. 23.

The stadium was dedicated as Dyche Stadium, honoring William Dyche, and finally declared finished — despite numerous future additions planned — for the Nov. 13 game against UChicago.

The home team’s win gave it a 7-1 record in 1926, tying Michigan for the Big Ten title — Northwestern’s first since 1903.

In the UChicago game program, Indiana University president Z.G. Clevenger described Dyche Stadium as “undoubtedly one of the very finest in the country,” and Intercollegiate Conference commissioner of athletics John Griffith wrote the “achievement means more than the completion of a modern athletic plant, rather it typifies the progressive spirit and vision of the leaders of a great university.”

In retrospect — and even at the time — one could hardly blame NU for feeling fully satisfied with its 45,000-seat Dyche Stadium.

“It certainly helped put Northwestern on the map and made them a more legitimate program than what they were (before),” Leonard said.

Team, stadium plan fades away

The rushed schedule for construction inflated costs well above projections, forcing some financial scrambling despite the program reaping record ticket sale revenue.

Even sans a second deck and towers on the east side, the final construction costs were nearly $1.5 million — almost double the original projection. The sale of fundraising bonds proved insufficient to cover the total cost, and more than $200,000 had to be “advanced from University Educational Funds,” according to typewritten financial records from the time.

Thus, the plans to add the upper east-side deck, two east side towers and permanent double-decker north and south endzone stands became more of a possibility than a guarantee.

In a report on the construction process, Norman Schmidt (Engineering ’25) wrote that “if attendance merits it, the east side will be completed so that both sides are symmetrical.” Schmidt also described, in the same report, “provisions for future expansion to an ultimate capacity of some 80,000 people by completing end sections and providing third decks on both the East and West sides.”

In other words, the idea of an 80,000-seat Dyche Stadium had become the potential expansion on a potential expansion.

A January 1928 edition of The American Architect periodical included a cross-section sketch of the stadium with three decks, but the game program for the 1927 season opener against Utah was the last time it was ever mentioned in official university publications from the era.

On the field, the Wildcats continued to be one of the nation’s more formidable programs. NU entered the final games of both its 1930 and 1931 seasons undefeated before losing both times. Even through those glory days, however, Dyche Stadium was not regularly reaching capacity: Only 42,000, for example, came out to see NU beat Minnesota at homecoming in 1931.

By the time NU football hit rock bottom in 1981, with three total wins over a six-season span, the average attendance was in the range of just 20,000 per game.

Nearly a powerhouse

The window for NU to explode into a national powerhouse of a football program, both on the gridiron and in the stands, was slim — but there unquestionably was a window.

The Chicago Bears were mired in a shaky first decade and had yet to earn a significant following around the metropolitan area, and NU’s 1926 win over UChicago helped to shift the city’s balance of football power permanently toward Evanston.

Meanwhile, the window was open for new universities to move into the realm of college football’s elite, which was left largely vacant by the decline of the once-dominant Ivy League: Cornell and Princeton’s joint national championship in 1922 was to be the league’s last.

Stanford, another academically high-achieving private school, had only birthed its football program in 1918 and, by 1927, boasted the nation’s largest stadium and three Rose Bowl appearances in four years. Neither Michigan nor Ohio State — now considered the crown jewel programs of the Big Ten — was a noteworthy dynasty at the time, either. Ohio State, for example, went 3-4-1 and averaged fewer than 30,000 fans per game in its brand-new, 66,000-seat Ohio Stadium in 1923.

NU experienced arguably as much success as any other team in the nation, save for Notre Dame, between 1926 and 1931. The Wildcats legitimately appeared to be on the verge of establishing themselves as one of the Big Ten’s powers for decades to come.

With players coming and going every four years, however, the key to maintaining that elite program status might have been a world-class stadium — a world-class stadium that NU only almost had.

After a largely dismal remainder of the 20th century, the Wildcats have re-emerged as a decent program in recent decades, and Ryan Field has developed with age an undeniable “charm” and “uniqueness to it,” in the words of coach Pat Fitzgerald.

But the stadium remains the smallest in the Big Ten, far from the 80,000-seat behemoth once outlined by its architect, Rogers, and NU finds itself the second-losingest program in FBS history.

One can only imagine how a different structure on Central Street might have altered the course of Wildcats football over the past 90 years.

Email: benjaminpope2019@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @benpope111