Deciding divestment: Northwestern student activists face obstacles beyond their control

May 22, 2015

On the night of Feb. 18, more than 400 people crowded into Norris University Center for an impassioned debate about a resolution asking Northwestern to divest from six corporations the resolution’s sponsors say violate Palestinians’ human rights.

More than five hours after the debate began, the resolution narrowly passed in Associated Student Government Senate, with 24 votes in favor, 22 votes against and three abstentions.

More than three months after the vote, the resolution hasn’t resulted in any policy change — or divestment.

Contemporary student divestment movements face obstacles imposed by forces beyond campus. Today, NU’s investments are much less transparent than in years past after a switch to indirect investment in the 1990s made it much more difficult to know what the University does or doesn’t hold. Reluctance to stray from what some call a politically neutral stance, coupled with a financial responsibility to make a large return on investments also influence investment decisions.

The history of student calls for divestment at NU indicates student activism often has little to do with divestment decisions.

Former University President Henry Bienen, who joined NU in 1995, was president during the campaigns to divest from Burma and Sudan. Frankly, he said, it would take a lot more than student support for the University to choose divestment.

“I wasn’t personally swayed by issues of student activism,” Bienen said in an interview with The Daily last month. “We have our own policies and way we go about the process of making decisions.”

A ‘token’ response

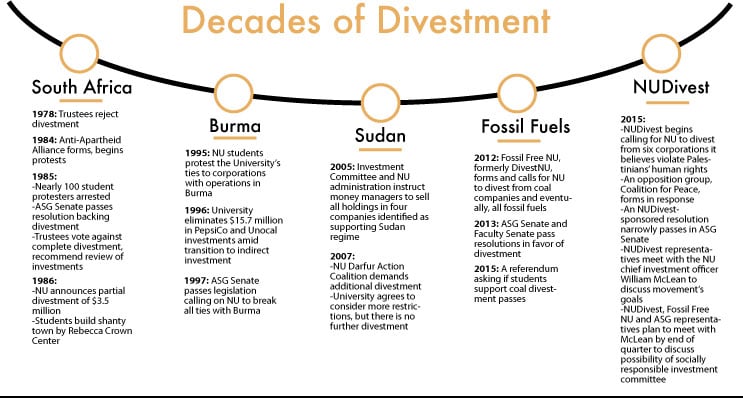

Amid an international movement against apartheid in South Africa, the first notable push for divestment at NU fell flat when a September 1978 report submitted by a Board of Trustees committee rejected divestment.

“We are impressed with the sincerity of the views expressed on both sides of the question,” the committee wrote. “But we are not persuaded that Northwestern’s selling of its investments would have any discernible ameliorative circumstances.”

The Anti-Apartheid Alliance formed in 1984 and over the next few years intensely advocated for complete divestment from companies doing business in South Africa. Joshua Lazerson, who received a doctorate in history from NU in 1990 and spearheaded the alliance, said although the group and the administration had a cordial relationship, the University was more interested in the financial returns from investment than activism.

“We felt that what we were attempting to achieve was more important than the University’s own agenda,” he said. “There was tension there, no questions about it.”

Lazerson was among more than 100 students arrested during protests at the Rebecca Crown Center in Spring Quarter 1985. One of the protests lasted several days, and at one point about 150 students stormed the president’s office, demanding divestment.

Soon after the protest, an ASG resolution calling for divestment passed in Senate 30-1. In November, a second trustee committee formed to study issues of divestment released a report rejecting complete divestment, instead recommending review of investments on a case-by-case basis.

A few days after the report, NU formed a subcommittee within the Board of Trustees to review the University’s portfolio. In March 1986, the University announced the subcommittee’s decision to divest $3.5 million from two companies out of the more than $166 million it had invested in companies with ties to South Africa.

“They did a few token things, but they didn’t take any real meaningful or majority action when it came to changing the University’s investments,” Lazerson said.

Bienen said a university will choose divestment only in extraordinary circumstances, such as when a government’s actions are universally condemned. He pointed to Nazi Germany as an example of an exceptional situation that would require divestment. South Africa, he said, was similarly “extreme.” In the case of South Africa, the Board of Trustees followed U.S. government guidance by considering the Sullivan Principles — a corporate code developed to protest apartheid by promoting social responsibility guidelines for corporations — in its investment decisions.

However, even as a dedicated student activist, Lazerson said, he never expected total divestment.

“It was clear to me from very early on that the board and the president were not going to be easily swayed by this,” he said.

Because of the often politically-charged nature of divestment, Bienen said, universities typically follow U.S. government policies when making investment decisions, as NU did with South Africa. He said such a “safe haven policy” helps keep universities from taking a political stance.

“People who are on your board tend not to like divestment,” he said. “Their preference is to not have politics attached to investment decisions for lots of reasons.”

Donors’ primary interest when giving to universities is maximizing their investment, Bienen said.

“They’re not saying, ‘Be political on social issues, be political on issues of foreign policy or domestic policy,’” he said. “They’re saying, ‘We’re going to give you money and we want you to maximize the return.’”

Shifting strategies

The Investment Office transitioned from direct to indirect investment about 20 years ago.

The university’s in-house investment office stopped choosing the companies in which to invest, deferring such decisions to outside management firms, The Daily reported in July 1996.

Today, external money managers handle roughly 95 percent of the about $10 billion endowment, chief investment officer William McLean said. The Investment Office directly manages about 5 percent.

The University transitioned to external money managers as students called to divest from corporations operating in Burma, a country accused of violating human rights. The University phased out its $15.7 million in PepsiCo and Unocal investments, both companies that had operations in Burma, today known as Myanmar. At the time, then-President Bienen said it was merely a coincidence and a decision to align with the new investment strategy rather than a political choice.

Carwil Bjork-James (Weinberg ‘96), an activist who pushed for divestment, said although the University said it was a coincidence, he considers it politically motivated divestment.

“They never said we made a deal or conceded that it happened,” he told The Daily last month. “It’s hard not to read that as an expression of at least concern of criticism they were getting from students or being connected to some fairly ugly events happening overseas.”

NU again divested in 2005 when the Investment Committee and the University administration instructed the endowment’s external money managers to sell all holdings in four companies identified as supporting the government regime in Sudan. Students formed the NU Darfur Action Coalition and demanded additional divestment in 2007. The coalition asked NU to divest from almost 30 companies activists believed supported Sudan. NU agreed in 2007 to consider more restrictions amid student pressure. However, there was no further divestment.

Understanding the endowment

McLean said if the University wanted to divest, it would instruct the managers to do so.

NU’s endowment makes the university one of the richest in America. The endowment largely comprises donations to NU. Student tuition does not go into the endowment.

The Investment Committee guides the endowment’s management. There are more than 30 trustees on the Investment Committee. Both the full board and the Investment Committee convene quarterly, but the meetings are separate. He said divestment issues have been discussed at the last three Investment Committee meetings.

University President Morton Schapiro said work of the trustees and the Investment Office allows the University to invest in programs like Counseling and Psychological Services and facilities like the new Henry Crown Sports Pavilion.

“Those guys are magicians,” he said. “Everybody has to realize that.”

Schapiro said he respects student activism but didn’t agree with Senate’s vote on the NUDivest resolution.

“The students of Northwestern, the elected representatives did a vote that I might not agree with — don’t agree with,” he said.

However, administrator — and student — opinions have limited impact because actors outside the University decide where the money should go.

Bienen said only in rare circumstances does the University hold individual stock. In one such instance, he said, the University complied with a donor’s request for NU to hold shares in Pfizer Inc., a pharmaceutical corporation.

“That was an occasion where the donor made a very big gift,” he said. “It was a very rare example of holding stock.”

Bienen said NU doesn’t want the risk that comes with directly holding stocks. When donors give stocks as a gift, he said, the University almost always sells them.

Some funds hold money from only NU. Other funds hold money from multiple universities. Bienen said it is probably more effective for students seeking divestment to target the money managers directly, rather than NU.

‘The most important part is $10 billion’

All five major divestment movements at NU have had resolutions with student government support, but none have resulted in complete divestment. Even campaigns with widespread campus support did not or have not met their divestment goals.

Fossil Free NU, formerly Divest Northwestern, began in 2012 and calls for the University to divest from coal companies and eventually, all fossil fuels. ASG Senate and Faculty Senate passed resolutions in 2013 supporting divestment. In 2015, a referendum asking students if they support coal divestment was included on the ASG presidential election ballot, and passed with 74 percent of voters in favor of coal divestment.

The newest initiative, NUDivest, formed in Winter Quarter and is asking the University to divest from Boeing, Caterpillar, Elbit Systems, Hewlett-Packard, G4S and Lockheed Martin, companies it believes are complicit in the violation of Palestinians’ human rights. McLean said he would be “shocked” if the University didn’t hold indirect investments in Boeing or Caterpillar.

“It’s safe to say we own those companies,” he said. “They’re large companies. Whether we’ve got $2 million or $4 million or $6 million, Caterpillar or Boeing is not really the issue. … The issue is if you’re going to sell it.”

No campus divestment movement at NU has incited the kind of controversy between students that NUDivest has. Critics of NUDivest have associated the campaign with the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, which calls not only for divestment, but for boycotts against involved companies and sanctions against Israel. NUDivest maintains that the resolution calls for only divestment, not boycotts or sanctions. The same week NUDivest started its campaign, an opposition group, NU Coalition for Peace, formed in response to the divestment movement.

“People get focused on things like a march or a demonstration,” said Margaret Barr, former vice president for student affairs, in an interview with The Daily last month. “Students who do what I call work in the trenches … are just as effective as those who march. It’s not just going to the rally and shouting.”

Schapiro said “respectful engagement” is the most effective form of activism.

“I don’t think this is a place where disruption or any of that kind of stuff really convinces anybody to do anything,” he said. “Do a respectful presentation … That’s the best way to get what you really want.”

Following the Senate vote, NUDivest continues to host regular events and helped stage a mock checkpoint and border patrol demonstration last week during Students for Justice in Palestine’s Israeli Apartheid Week. Fossil Free NU is still pushing for divestment from fossil fuels, despite an Investment Committee vote against coal divestment in November.

NUDivest representatives met with McLean on May 8 to discuss the movement’s goals. Weinberg sophomore Marcel Hanna, who was at the meeting, said NUDivest sent an email to Schapiro but did not receive a response. Hanna said not being able to contact Schapiro is a big obstacle for the movement.

“As the president of the University, if students wish to meet with him, especially students in an official capacity that have a passed resolution,” he said, “I believe it’s his duty to meet with us or at least hear us out.”

University spokesman Al Cubbage said Schapiro did not receive an email from NUDivest.

Hanna said NUDivest plans to reach out to the Board of Trustees next.

McLean has met with Fossil Free NU multiple times. Weinberg sophomore Christina Cilento of Fossil Free NU said that although the group has broad support on campus, the main challenge is getting in contact with the Board of Trustees. Fossil Free NU had a meeting with a trustee in November, after the Investment Committee vote, and plans to submit a formal divestment proposal to the board when it convenes in June.

Cilento said the group’s biggest problem is with a lack of transparency from the Board of Trustees. She said because many trustees’ contact information is not readily available, reaching individual members is difficult.

“Navigating the bureaucracy of the University is so time-consuming,” she said. “It just blows my mind that the people who are supposed to represent the students and be the guiding figures of the University aren’t accessible.”

Cilento said McLean has said there is a possibility the board will vote again on coal divestment. Despite regular communication with the group, however, McLean said divestment from fossil fuels is a “slippery slope.”

“There are a lot of different issues out there,” he said. “How do you decide which ones have merit and which ones don’t? … It’s not what a university’s here to do.”

McLean said he often hears information about what issues students are interested in “third-hand.” However, McLean praised Fossil Free NU for clearly expressing its goals.

“(The) group is great because they’re very direct and say, ‘Here’s what the students have passed, here’s what we’re interested in,’” he said.

NUDivest and Fossil Free NU have both expressed support for the creation of a socially responsible investment committee. The NUDivest resolution also called for a committee dedicated to greater transparency in investments.

At an NU Political Union event in April, McLean said he was open to such a committee.

“There’s an argument for having one central place where some of these (investment issues) get vetted,” McLean said during the event. “We’re interested in hearing student voices, and maybe a committee is a better way to do it.”

Schapiro also said he supports the idea of such a committee. He said there was a similar committee when he was president at Williams College.

“It was very productive,” he said. “If (the board asks) me my experience with committees, I would say 100 percent positive.”

Faculty Senate supported a proposal to create such a committee in April and ASG created a task force to lobby for a committee in February. ASG President Noah Star, a Weinberg junior, and Executive Vice President Christina Kim, a McCormick junior, plan to meet with McLean, NUDivest and Fossil Free NU before the end of the quarter to discuss the possible creation of a committee.

Faculty Senate supported a proposal to create such a committee in April and ASG created a task force to lobby for a committee in February. ASG President Noah Star, a Weinberg junior, and Executive Vice President Christina Kim, a McCormick junior, plan to meet with McLean, NUDivest and Fossil Free NU before the end of the quarter to discuss the possible creation of a committee.

“The plan was always to get as much of the infrastructure in place as we could,” Star said. “What’s most important to me is that I want to do this the right way, the way that the people working for divestment want it to be done.”

Hanna said NUDivest and Fossil Free NU have drafted a mission statement about the committee, which they will discuss with McLean before the end of the quarter. NUDivest presented the statement to McLean during their May 8 meeting.

McLean said he is happy to meet with students, but there needs to be clear communication.

“This is an important part of our job, dealing with students, but it’s not the most important part of our job,” he said. “The most important part is $10 billion. … We’re trying to bend over backwards to meet with people and help them out and discuss these issues because they’re important, but it’s got to be a two-way street.”

Hanna said NU’s history with divestment needs to be addressed and points to a larger problem about the University’s values.

“We have absolutely no history of socially responsible investment policies,” he said. “If we want to claim to be a progressive institution, we have to have socially responsible investments and we have to care about how we affect the world.”

Graphic and timeline by Mande Younge/Daily Senior Staffer

Daily file photos by Rick Phillips, Jeanne Kuang and Sean Su

Email: exstrum@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @oliviaexstrum