Faculty to call for Asian American Studies major 20 years after hunger strike

May 6, 2015

Twenty years after a hunger strike to establish the Asian American Studies Program shook Northwestern’s campus, the program’s faculty plans to submit a proposal to establish an Asian-American studies major.

History Prof. Ji-Yeon Yuh, the first hire for the Asian American Studies Program in 1999, said faculty will submit a proposal before the end of 2015 to create a major.

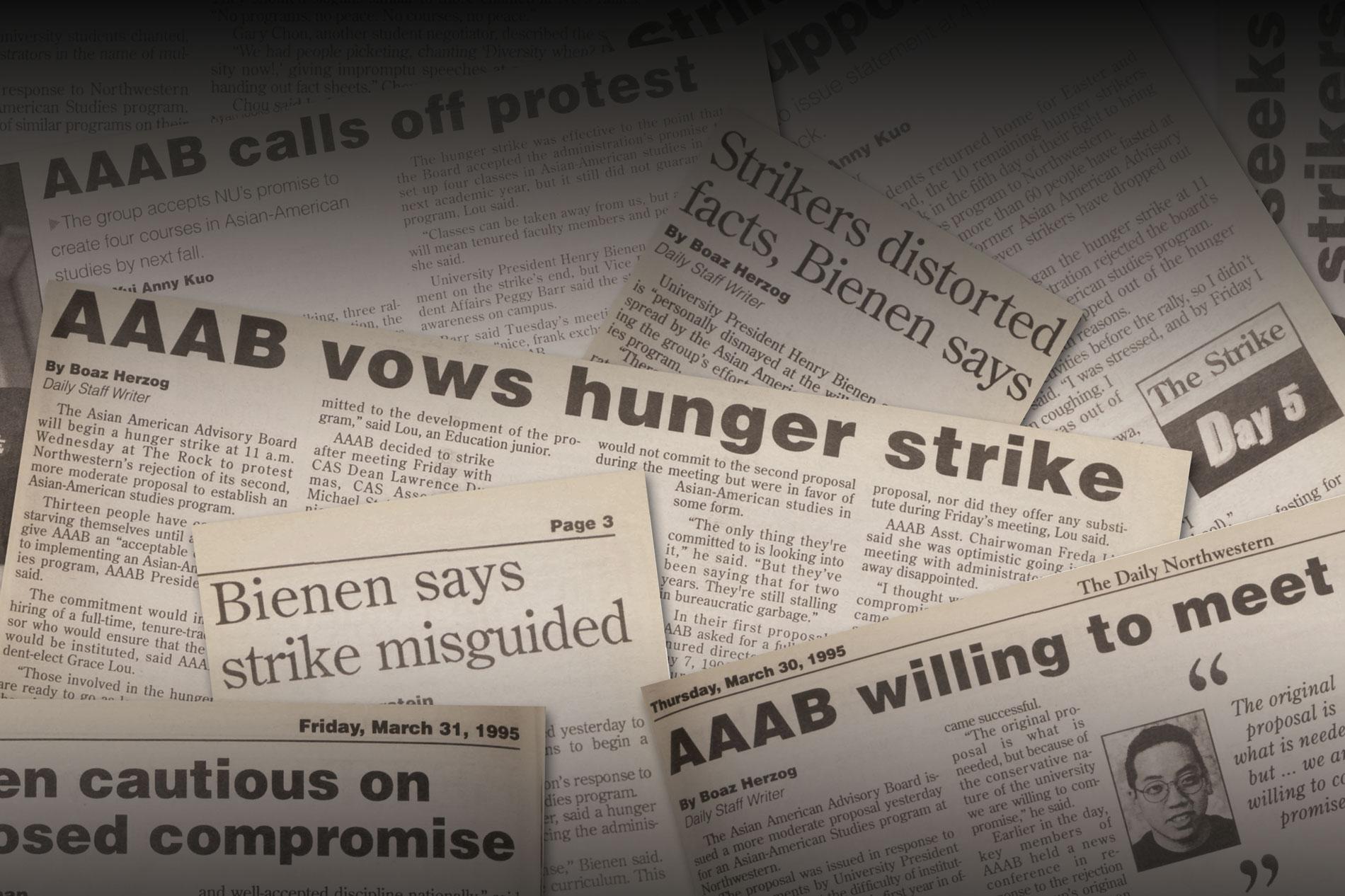

In 1995, students became frustrated with the administration’s lukewarm response to a proposal to establish the program and began a hunger strike in protest. The 200-page proposal included letters of faculty support and more than 1,200 student signatures.

The hunger strike ended after 23 days when the students realized the administration did not have immediate plans to establish an Asian-American studies program.

The University established the program four years later. To this day, the program has only a minor, although students repeatedly asked for a major. Even though the drive to create the program helped pave the way for other ethnic studies programs at NU, other attempts have faced similar administrative roadblocks.

‘Do you think I’m going to stay quiet?’

In a paper for an NU class, David Hish (Communication ‘95) recalled he jokingly suggested in 1994, “We should all go on a hunger strike and chain ourselves to the clock tower,” if the administration rejected a proposal from the Asian American Advisory Board for an Asian-American studies program. The student group submitted the proposal in February 1995.

About two weeks later, then-University President Henry Bienen issued a statement thanking AAAB for bringing the issue to his attention, saying he would direct the suggestion to a curriculum committee, but would not pledge to the establishment of an Asian-American studies program.

Before the 1995 proposal, members of AAAB said they had also submitted multiple proposals beginning in 1991 for an Asian-American studies adviser.

Hish had no idea a comment he made in passing would become a reality, he told The Daily last month.

On April 12, 1995, 17 students began a hunger strike after the administration did not satisfy AAAB’s demands.

At an opening rally, then-AAAB chair Grace Lou (SESP ‘96) challenged Bienen to address the strikers’ requests.

“Come on out,” Lou shouted outside Hardin Hall, The Daily reported in 1995. “Do you think I’m going to stay quiet? I want you to look me straight in the eyes and tell me Asian-American studies doesn’t matter.”

Students rally on April 12, 1995, criticizing administrative resistance to the creation of an Asian-American studies program. That day marked the start of a 23-day hunger strike.

Strikers wore yellow armbands and camped out at The Rock. Students took vitamins and drank liquids for sustenance during the strike, said Michael Yap, one of the original hunger strikers. Yap, who graduated from the University of Chicago in 1994, is the brother of a former AAAB chair Rob Yap (Weinberg ‘95), who was also involved in the protest.

The Daily reported that on the second day of the strike members of the Conservative Council, a right-wing student group, mocked the hunger strikers by passing out pizzas near the strikers’ tents.

After 12 days, Charles Chun (Weinberg ‘97) dropped out of the hunger strike. He was the last striker who had been participating since the beginning and had lost 20 pounds.

“Fasting becomes so personal,” Chun told The Daily at the time. “The only person who was going to quit was me.”

On April 20, 1995, students at Stanford, Princeton and Columbia universities supported the NU hunger strikers through solidarity events, including a fast and a sit-in, The Daily reported.

“It was a political strategy designed to draw media attention to the problem: the problem of invisibility, the problem of being perceived as a model minority, people who weren’t going to rock the boat,” said Sumun Pendakur (Weinberg ‘98), who participated in the strike. She is now the associate dean for institutional diversity at Harvey Mudd College in California.

The strike ended and the students were still empty-handed. For the next few years, AAAB led rallies, teach-ins and marches down Sheridan Road.

The Asian American Studies Program was finally established in 1999, with Yuh as the program’s first hire. Yuh served as program director from 2005 to 2010.

“I wasn’t even sure that we were going to get it while I was … a student,” said Vishal Vaid (Weinberg ‘01), who participated in the push for the program and was one of the first two people to graduate with the Asian American Studies minor. “To see it actually happen and to also be able to attain it, it was justice.”

Beyond the strike

NU’s history of student-driven initiatives to establish academic programs and departments started even before the hunger strike.

The African American Studies Department was created in 1972 in response to the May 1968 sit-in at the Bursar’s Office. The 38-hour occupation by students from For Members Only led to negotiations and administrative commitment to increase awareness related to black studies.

Programs differ from departments in that programs cannot tenure their faculty. Rather, program faculty members have tenure homes in departments.

“We don’t have any real intellectual autonomy,” said Asian American Studies Prof. Jinah Kim. “That is a very significant thing.”

NU established a major and minor for Latina and Latino studies in 2009 after a student and faculty initiative. Yuh, who supported the creation of the program, said the history of the hunger strike helped facilitate the process for the establishment of the Latina and Latino Studies Program.

“The students didn’t have to do a noisy demonstration,” she said. “That’s largely because Asian American Studies was here.”

The most recent push for a new ethnic studies program — a Native American studies program — faces similar roadblocks.

Students have expressed interest in creating a Native American studies program for more than 20 years, said Yuh, who spoke to several students about the matter when she came to NU in 1999.

However, even though people were passionate, the interest was not widespread, said Mary Finn, the associate dean for undergraduate academic affairs.

In 2012, the Native American and Indigenous Student Alliance petitioned the University to look into the role Evans, the University’s founder, played in the Sand Creek Massacre. The petition also called for the creation of a Native American studies program.

After the petition, the University formed a study committee that concluded Evans had no direct involvement in the massacre but that NU ignored “significant moral failures.” Another committee submitted a series of recommendations to improve relationships with Native American communities, including establishing an Indigenous Research Center. Within that research center, the report recommends the creation of a certificate or minor in “Indigenous studies.”

“(The petition) put the administration on a hot seat and made John Evans a salient issue on campus,” said Forrest Bruce, co-president of NAISA and a member of the committee that submitted the recommendations. “Things just started moving along after that.”

Although the University has moved forward with the recommendations, Bruce said NU seems to lag in creating the program.

“It seems like they’re more concerned with the PR that goes with the Sand Creek Massacre as opposed to actually trying to right what has happened,” the SESP junior said. “It makes for a lot slower process, like getting things like a (Native American) studies program.”

Provost Daniel Linzer said creating a program takes time, something students fail to realize.

“There is more energy behind certain ethnic studies programs, where people want to see much more rapid change,” he said. “That leads to some frustration.”

So far, the University has taken steps toward creating the Native American studies program, Linzer said. Several courses have been launched to see whether there is student interest and a new professor focusing on Native American literature was hired, he said.

“Dealing with the University, you come into the role where we need to keep applying constant pressure and constant scrutiny to really get the University to go through with anything,” Bruce said.

Psychology Prof. Douglas Medin, NAISA’s faculty adviser, noted a difference between the pushes for Asian-American studies and Native American studies programs.

“In the case of Native Americans, we don’t have the presence of a large number of Native American (students) who would be in a position to exert that kind of pressure,” he said. “We’ve done such a poor job of recruiting Native scholars that we’ve created a situation where the impetus of change is not going to come from our current Native students.”

Ultimately, Bruce hopes NAISA’s efforts will result in tangible change.

“They’re committed to do what they can to have us shut up … They definitely want to stop the scrutiny,” he said. “Having a (Native American) studies program will satiate a lot of what we want.”

New dean, new possibilities?

In July, Adrian Randolph, an associate dean at Dartmouth College, will start his term as Weinberg dean, replacing chemistry Prof. Mark Ratner, the school’s interim dean.

Although he is not opposed to establishing more ethnic studies programs, Randolph said creating a Native American studies program is not necessarily going to be one of his immediate priorities.

“It can be very problematic to keep on proliferating structures,” he said. “For example, every structure has to have a chair, staff, people who are devoting a part of their life to administering the program.”

Dartmouth went through a period of producing a lot of programs, which became an issue for the institution, Randolph said.

“At some point, you start thinking what is the limit? How many programs can we produce?” he said. “Is there a structural problem when we produce that many?”

Come July, Randolph said he hopes to focus on Weinberg as a whole and review all the possible areas of growth within the college.

“Change won’t come just overnight,” he said. “I know it’s a cliche, but I think I will be listening. … I will be trying to learn what are the strengths and weaknesses of the present system and what are the exciting ideas people are bringing to my office and to my attention.”

Striking back

While the Native American studies program continues to develop, the Asian American Studies Program is preparing for a move of its own.

Although the program hasn’t visited the matter of establishing an Asian-American studies major with the administration for a few years, Yuh said that would hopefully change soon.

Yuh said they hope to have the proposal to University administrators before the end of the calendar year.

Finn said there wasn’t enough student interest to create an Asian-American studies major.

“The number of minors never justified the expansion to a major,” she said. “(They) have stayed fairly steady and pretty low relative to other majors and minors.”

Yuh hopes this time around, however, the proposal will be different. There has been steady student interest in declaring an ad hoc major, which requires students to create their own academic plans for an Asian-American studies major, she said. In addition, the number of students pursuing minors has more than doubled to 25 since the last time the program proposed a major to the administration.

“The program is more settled in some ways, and we do now have this track record of ad hoc majors,” she said.

Anthropology Prof. Shalini Shankar, the current director of the program, said student support is crucial to the program.

“Honestly, the administration listens to students so much more than they listen to faculty,” she said. “We can propose something, but we need (students) to back us up.”

Graphic by Jacob Swan/The Daily Northwestern

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @benjamindin