In Focus: Trial of the heart: Woman says Northwestern cardiac surgeon used ‘human experimentation’

Senator investigates a woman’s claim her doctor implanted an experimental device into her heart valve — without her consent

May 16, 2014

Antonitsa Vlahoulis struggled to get the words out as she remembered the medical ordeal that kept her away from her children and in and out of hospitals for months.

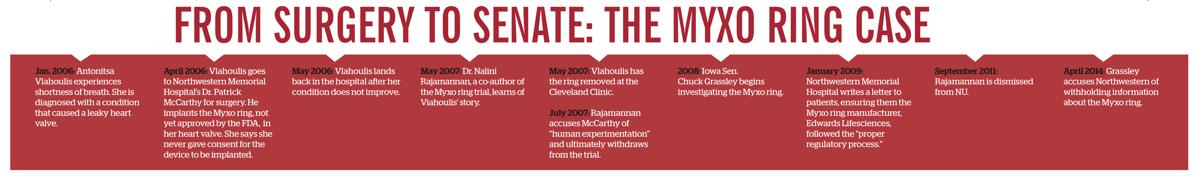

Vlahoulis first came to Northwestern Memorial Hospital in 2006, when shortness of breath made it difficult for her to exert herself at her job as an X-ray technician. She was diagnosed with a condition called mitral valve prolapse, which caused her heart valve to leak severely.

Months after having open heart surgery, Vlahoulis realized her surgeon, Patrick McCarthy, had implanted a ring that was part of a clinical trial she says to which she never consented.

“How could you do that to someone?” the Niles woman told The Daily as tears formed in her eyes. “I felt like I was being treated like an animal.”

Vlahoulis, 46, is one of more than 600 patients from 2006-08 who were implanted with the Myxo dETlogix 500 Annuloplasty Ring 5100, a triangular piece of silicone and metal that pinches together leaky heart valves. McCarthy, the chief of cardiac surgery at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, invented the ring.

Another top doctor on the trial, Nalini Rajamannan, accused McCarthy of “human experimentation” after hearing Vlahoulis’ story in 2007. Her accusations sparked a U.S. Senate investigation, and the controversy over the ring appeared in the Chicago Tribune and The Wall Street Journal.

Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) reignited the case this year when he accused NU of withholding information about the Myxo ring he first requested in an investigation five years ago. The Senate Judiciary Committee’s top Republican said the University failed to adequately respond to his request again in 2014.

NU spokesman Al Cubbage said the University is preparing a response to Grassley’s April letter.

Although University President Morton Schapiro was not at NU when the controversy started, he said administrators have been looking into the issue “for years and years and years.”

“There are a lot of things that we review,” he said in an interview last month. “And typically move on unless we find something inappropriate.”

“It’s been a continuing issue but I think by and large… the University has responded to all the requests we’ve received,” Cubbage added.

McCarthy remains the chief of cardiac surgery and director of the Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute at Northwestern Memorial Hospital.

“Claims of human experimentation are absolutely false,” McCarthy wrote in an email to The Daily, declining a request for an interview.

But eight years, a Senate investigation and at least two lawsuits later, Grassley says the University still hasn’t answered a simple question.

“Did Northwestern implant an unapproved device — which it knew, or should have known, required approval — in patients without obtaining their informed consent?” Grassley wrote in an April 28 letter to the University.

Grassley says that answer will have major implications for a broader discussion about what patients deserve to know before receiving a medical device.

‘I just wanted to feel better’

In spring 2006, Vlahoulis was referred to McCarthy for surgery to fix her mitral heart valve. Before the surgery, she said, she sat in his office as he showed her brochures of the different valves and rings he might implant in her heart.

McCarthy said he wouldn’t know exactly which one he would use until he opened her up, or whether he would replace her valve with a mechanical one or repair the valve with a ring. In any case, he said, it would be one of the types in the brochure.

The Myxo annuloplasty ring wasn’t listed, she said.

Before her operation, she said she signed a standard surgical consent form.

Vlahoulis also agreed to be a part of a medical database for atrial fibrillation, a type of heart arrhythmia where the heart contracts too fast and irregularly. She said McCarthy said he would do a “two for one” procedure that would change the electrical path conduction of her heart. McCarthy told her she would be part of the database because she was a relatively young patient, and he wanted to follow up with her after the surgery, she said.

“He said once I had the surgery, I would feel like a million bucks,” she said. “I couldn’t wait to have the surgery done. … A lot of people, it’s open heart surgery, they have these fears. For me, I just wanted to feel better.”

But after Vlahoulis woke up, she knew something wasn’t right. Her shortness of breath was worse. She waited it out, thinking when the swelling from the surgery subsided she would feel better. But her condition only worsened, and she landed back at the hospital, this time in the emergency room three weeks after her first surgery.

The then-38-year-old mother of two found herself being pushed through a revolving door of hospital visits. In November 2006, she couldn’t breathe after even small exertions, like holding her 3-month-old godchild during a christening.

Vlahoulis continued to see her doctor, Rajamannan, who could not figure out what was wrong. She tried to contact McCarthy when she was in the hospital again, but McCarthy referred her to a psychiatrist, she said.

As her condition worsened, Vlahoulis searched for the warranty card for the device McCarthy implanted that the manufacturer, Edwards Lifesciences Corp., had sent her. She said she tried to research the McCarthy Annuloplasty Ring, as it was called at the time, but found nothing. She said it was not in the brochures McCarthy showed her.

When Vlahoulis asked Rajamannan, who initially co-authored the Myxo ring trial with McCarthy, why she couldn’t find anything about the ring, Rajamannan was confused. She told Vlahoulis she signed a consent to be part of a clinical trial.

Vlahoulis said she never did.

Blowing the whistle

Rajamannan says she was in shock when Vlahoulis told her that she did not know she had consented to an experimental procedure. She said she reported misconduct to Northwestern in July 2007. She says McCarthy believed everything was by the books and continued with the trial, without her name on it.

In the aftermath of Vlahoulis’ disclosure, Rajamannan agreed the patient should get a second opinion. Vlahoulis flew to the Cleveland Clinic in March 2007. Her doctor at the Cleveland Clinic was a former colleague of McCarthy’s and knew his strong reputation in the cardiovascular field, Vlahoulis said. She said he assumed McCarthy did nothing wrong.

But the ring was too tight, and after procedures continued to fail at NMH, Vlahoulis found herself back in McCarthy’s office, seeing the doctor for the first time since her unsuccessful surgery, a year later.

She and her husband asked McCarthy why she was not told she was part of an experimental trial.

“He looked down, with his legs crossed, twiddling his thumbs,” Vlahoulis said. “Then he changed the conversation.”

Vlahoulis said McCarthy told her the mitral valve in her heart would need to be replaced. But Vlahoulis said she knew she could no longer trust McCarthy to do it, and even though it meant being far from her children, she went to Cleveland to have the ring removed on May 21, 2007. She had her valve replaced with a mechanical one and had a pacemaker implanted.

After some complications with the pacemaker, Vlahoulis found herself back in the hospital and needed to return again to Cleveland in August 2007. Rajamannan flew there with Vlahoulis, who had another surgery to fix the pacemaker. After, she said she “felt like a new person.”

The aftermath

The entire ordeal left Vlahoulis and her children traumatized, she said.

“I don’t want to be part of a trial,” Vlahoulis said. “I’m too young to be part of a cardiac trial.”

Rajamannan, who said she was seen as a rising star at NMH, found herself on the receiving end of hostility from NU. She was terminated in fall 2011, when she was denied tenure.

(Northwestern cardiologist blames denied tenure on whistleblowing activities)

Vlahoulis and Rajamannan sued NU in the wake of the unsuccessful surgery, but their complaint was dismissed. Vlahoulis filed another complaint alone, but she eventually dropped the suit due to mounting legal fees.

Another patient also sued the University: Maureen Obermeier, a then-50-year-old patient who also received a Myxo ring implant, continues a legal battle with NMH, Northwestern Medical Faculty Foundation, McCarthy and the Myxo ring manufacturer. Obermeier suffered a heart attack in November 2006 on the operating table during the implantation, but she says no one told her at the time.

McCarthy’s attorneys denied all these claims.

A hole in the system

According to a 2009 letter from the Food and Drug Administration to Vlahoulis, the Myxo annuloplasty ring was not submitted for FDA approval until October 2008. Since July 2009, it has been deemed “investigational.”

But according to a clinical trial that McCarthy published, the ring was first implanted in patients in March 2006. Vlahoulis received hers in April 2006.

In a letter to patients who received the Myxo ring in January 2009, NMH wrote that the ring was not investigational and was commercially available at the time of their surgeries. The letter followed media reports alleging the FDA had not approved the ring.

“We have relied upon the manufacturer, Edwards Lifesciences, to follow proper regulatory process to clear the device for market and we have been assured by Edwards that it did so,” the letter read.

The Myxo annuloplasty ring falls in a gray area in the FDA approval process for medical devices. According to a letter addressed to Vlahoulis, the Myxo annuloplasty ring “was not originally covered” under the 510(k) approval process, which evaluates new devices before they are sold. As such, the ring would have to be studied under an “investigational device exemption.”

But McCarthy, NU or Edwards Lifesciences did not submit the Myxo ring for FDA for approval until October 2008.

The Myxo ring did not receive full FDA approval until 2009. Rajamannan says that approval was based on the clinical trial McCarthy published, which did not include Obermeier’s heart attack because she was exempt from the study due to another heart condition.

The FDA was unable to comment as of press time.

Because medical devices evolve so rapidly, the standards on when companies need to notify the FDA about changes made to medical devices remain a gray area.

Grassley says his inquiries about the Myxo ring are particularly important because of this ambiguity.

“Are doctors and hospitals performing their own due diligence to know whether a device needs FDA approval rather than accept assurances from a manufacturer that approval isn’t necessary?” he wrote in an email to The Daily. “Are patients learning of the risks associated with the medical device they will receive and giving informed consent for the device? These are some of the questions that the Northwestern case brings forward.”

New documents

Grassley has again probed into the Myxo case, after Rajamannan uncovered new documents she said show that the Northwestern Institutional Review Board said the trial results McCarthy published in The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery in 2008 did not require patient consent.

The IRB is an ethical committee responsible for reviewing biomedical research involving humans. According to the University’s IRB handbook, cardiovascular annuloplasty rings, like the Myxo ring, fall under what is known as “significant risk devices.” FDA rules require that informed consent be obtained for studies using both significant and non-significant risk devices.

According to a document obtained by The Daily, McCarthy signed an IRB form that waived patients’ right to informed consent to be used in his clinical trial in June 2006. This was two months after he had already implanted the ring in Vlahoulis.

The University denied accusations that patients did not receive informed consent, writing to Rajamannan in 2008 that “use of patient data from the registry was IRB approved and proper informed consent was obtained.”

Vlahoulis also received a letter from the University in 2008 saying she had consented to the release of her medical records for research purposes. Don Workman, then-executive director of the office for the protection of research subjects, and Ann Adams, then-associate vice president for research integrity, attached the consent form Vlahoulis signed to be part of the atrial fibrillation database McCarthy proposed to the IRB in 2005. However, the consent form makes no mention of the Myxo ring.

Rajamannan says the IRB should have looked into McCarthy’s June 2006 proposal more carefully when he requested to use the Myxo ring in his clinical trial.

Grassley said the documents related to McCarthy’s June 2006 request, including the patient consent waiver, should have been included when he first requested documents from the University in 2008 and 2009.

In a March letter responding to Grassley’s inquiry about the missing documents, the University wrote it believed it had fully cooperated with the senator’s staff in 2008 and 2009, and provided the additional documents Grassley requested. Grassley’s office could not publish NU’s attachments because they contained privileged information.

Grassley replied that the documents reveal continuing inconsistencies in the case of the Myxo ring. He said McCarthy made conflicting statements about the Myxo ring and how it compared to existing annuloplasty rings on the market.

In one report, McCarthy writes the ring is “significantly larger than existing commercial remodeling rings.” In another, McCarthy said he was assured by Edwards no FDA approval was needed for the new ring because it was a “minor modification” to an existing product.

‘Never the same’

Rajamannan, now a cardiologist at the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus Cardiology and Valvular Institute as well as a visiting scientist at the Mayo Clinic, says she wants patients to know the truth about the devices that were implanted in their hearts.

In February, Rajamannan found the June 2006 IRB consent waiver signed by McCarthy in Cook County Court. She submitted it to the Judiciary Committee, prompting Grassley to reopen his investigation.

“The study should have stopped and informed consent given to patients,” Rajamannan wrote in an email to The Daily. “(I’m) trying to protect the patients and to protect the integrity of Northwestern University from unauthorized human experimentation during open heart surgery.”

Grassley has called on the University to respond to his most recent letter by Friday, Rajamannan said.

“The issues here are important to resolve,” he wrote in an email to The Daily.

Vlahoulis said she is “very grateful” to Grassley for following through on his investigation.

“He has continued to seek the truth regarding the testing of the Myxo device during my open heart surgery,” she wrote in an email to The Daily.

Since Vlahoulis first had surgery more than eight years ago, she said, she feels the effects of her heart condition and ensuing complications every day, like on Easter, when she became short of breath while talking to her family members.

The once-active mother said she can no longer bike 13 to 20 miles a day like she once did or get through a day at work without getting tired.

“I’m never the same,” she said. “Dr. McCarthy walked away without even a slap on the wrist.”

Clarification: A previous version of this story suggested only one suit had been filed. It has been updated to include that Vlahoulis filed an additional lawsuit after the first was dismissed.

Email: catherinezakrzewski2015@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @Cat_Zakrzewski