‘A sense of continuity’: Foster and King Lab alums reflect on the schools’ legacies

Alumni of Foster School and Martin Luther King Jr. Laboratory School reflect on the schools’ legacies.

May 3, 2022

When Kimberly Holmes-Ross attended the Martin Luther King Jr. Laboratory School in the 5th Ward from 1969 to 1974, she said her education was carried out with intention and “magic.”

“We danced, we built things that we were proud of, we painted murals, all in the name of learning,” Holmes-Ross said. “We learned we were special, that everyone was special in their own way.”

King Lab had replaced the Foster School, the 5th Ward’s neighborhood school, earlier in the ’60s. King Lab was created as a magnet school in an attempt to integrate elementary schools in Evanston/Skokie School District 65. Prior to the shift, Foster School had been almost entirely Black, but once it became a magnet, the district began busing white children into the ward and busing many Black students to schools outside the ward.

The King Lab program shifted to the 2nd Ward in 1979, which is where the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Literary & Fine Arts School is now. The old Foster building ceased to operate as a school. But following a March decision by the District 65 Board of Education, the 5th Ward will soon have a neighborhood school for the first time in over 50 years.

“I’m hoping there’s some magic leftover from the previous school,” Holmes-Ross said about the new 5th Ward School. “I’d love to see them just really be innovative.”

At King Lab assemblies, she said, students would often sing “Lift Every Voice and Sing” instead of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Students at the school received instruction from multiple teachers and worked in multi-age groups based on their needs.

Lisa Disch attended Foster for kindergarten in the class of 1966 and graduated from King Lab five years later. She said the curriculum focused on raising children’s awareness of racism.

But Disch, who is white, recognized the lasting inequities caused by the shift to a magnet school model and the eventual closure of the Foster building as a school.

“To me, it was an amazing and life-changing experience,” Disch said. “But I am very aware that as an experiment in a highly hyper-segregated city of Evanston, it did not go smoothly.”

While many families were excited about the new King Lab curriculum, some Black families felt communication from the district let them down. Many were blindsided when their children ended up being bused to schools outside the district, according to the 1967 short documentary “The Integration of Foster School.”

While King Lab was integrated, Holmes-Ross said integration only lasted during the school day. The bus she took back home, she said, was entirely Black, and other buses were mostly white.

“It was integrated and kumbaya,” she said. “And then three o’clock came, and then we went back to our separate way.”

Carlton Moody, who grew up in Evanston and taught at King Lab, said he thought King Lab provided students an excellent education.

At the same time, he said some of his friends who had attended Foster felt they’d lost something.

“They didn’t necessarily feel at that time, ‘Oh, no, I’ve lost my neighborhood school,’” Moody said. “That’s something that comes up after the fact, that you realize that your neighborhood school has gone, and kids are being bused in from all over the city to come there.”

He said the students he knew from Foster had strong feelings about what their school represented: a neighborhood community.

A 5th Ward native, Holmes-Ross said her mother, former Ald. Delores Holmes (5th), attended Foster in the 1940s.

The goal of Foster School was to “have a place for Black kids to learn and excel,” Holmes-Ross said. “And be safe and be loved and just have a great learning experience in their neighborhood.”

Some Foster and King Lab alums are still involved in the community. Holmes-Ross said her mother belongs to a group of Foster alumni who have stayed in Evanston. According to Holmes-Ross, members of the group pushed for the new 5th Ward school to become a reality.

People Moody met at King Lab continue to be part of his life, he said. In October, he visited the Fleetwood-Jourdain Community Center, near the old Foster School. His grandson played basketball there, and unbeknownst to him, one of his old students was there too.

“A former student came up from behind and gave me a big hug and said, ‘There’s Mr. Moody,’” Moody said. “I had been his teacher 40 years ago. And here his son was coaching my grandson. So it’s a sense of continuity and one generation feeding into the next.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @avivabechky

Related Stories:

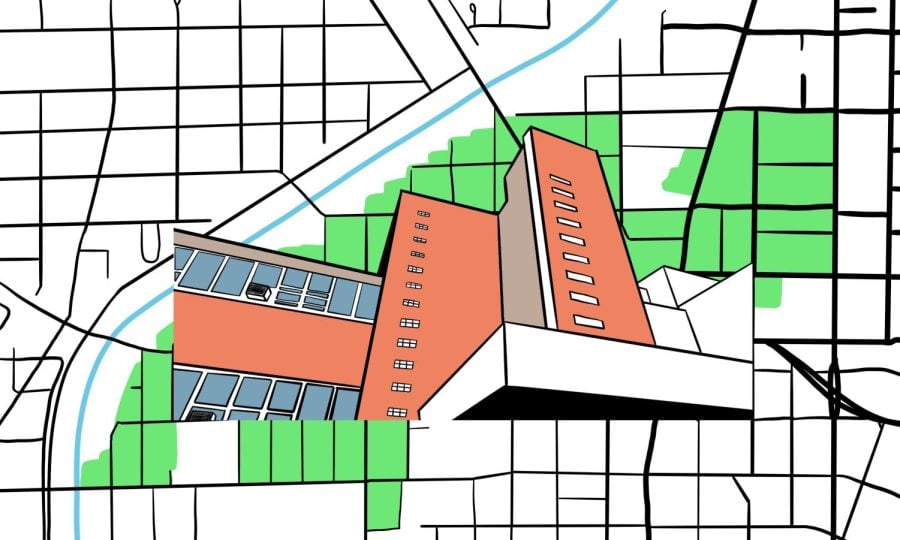

— From Foster to Family Focus: More than a century of District 65 decisions in the 5th Ward

— In Focus: Fifth Ward residents advocate for neighborhood school in historical building