In Focus: As NCAA proposal nears vote, college baseball and softball coaches seek to elevate volunteers to equal standing

April 15, 2019

It was the top of the eighth inning of the 2017 Big Ten Tournament semifinal against Maryland — a win-or-go-home game for the Wildcats — when Sam Lawrence delivered one of the most important pitches in Northwestern history.

NU entered the tournament as the No. 7 seed and was the Cinderella story of the weekend. But their magical run was on the verge of collapse. The Cats had a 6-5 lead, but the Terrapins had the bases loaded with one out and Zach Jancarski, Maryland’s speedy center fielder and lead-off hitter, at the plate.

After falling behind 2-0 to start the at-bat, Jancarski hit a grounder a few feet to shortstop Jack Dunn’s right. Dunn fielded the ball and threw it to second baseman Alex Erro. Erro caught the ball at second base, took his momentum across the base and fired to first. His throw edged out Jancarski — double-play, inning-over, no runs scored.

“Probably the best double play I’ve ever seen turned in person,” said former volunteer assistant coach Tad Skelley.

BASES LOADED, UP ONE, SAM LAWRENCE GETS THE DOUBLE PLAY.

THERE. ARE. NO. WORDS. #B1GCats | #SaddleUp https://t.co/V4ZHqXorWY

— Northwestern Baseball (@NUCatsBaseball) May 28, 2017

NU’s dugout erupted in celebration. For almost everyone watching the play, the turn was smooth, simple and spectacular.

Skelley said it was the proudest he has ever been as a coach. But he also knew there was more to the play than met the eye.

Earlier in the tournament, the Cats had a similar double play opportunity, but Erro stayed back on the throw from Dunn, and it cost the team an out. Skelley, who worked with infielders on defense, talked with Erro and Dunn about the mistake.

Just a few days later, Erro made an adjustment — and it became the most important play in a win that sent NU to the Big Ten championship game for only the second time in school history.

“Alex did exactly what we had talked about,” Skelley said. “That was pretty cool. That’s pretty special.”

That’s part of why Skelley looks back on his time with the Cats as “probably the best experience” of his life. He loves the players and the coaching staff and still keeps in contact with a good number of them.

Rocky and Bernice Miller Park, home of Northwestern baseball.

But by the time the new year began, Skelley was no longer on staff; he had started a job in the Toronto Blue Jays scouting department in January 2018.

Skelley was a volunteer assistant coach at NU for two seasons. That meant he was not paid, did not receive health insurance and could not recruit. With a family, including a 3-year-old daughter, the need for health benefits outweighed his passion for the job.

But things could have gone differently. When asked if he would have left Evanston if he were a full-time coach, Skelley was quick to respond.

“No.”

Soon, however, Skelley’s worries may no longer be a concern for current volunteer assistant coaches.

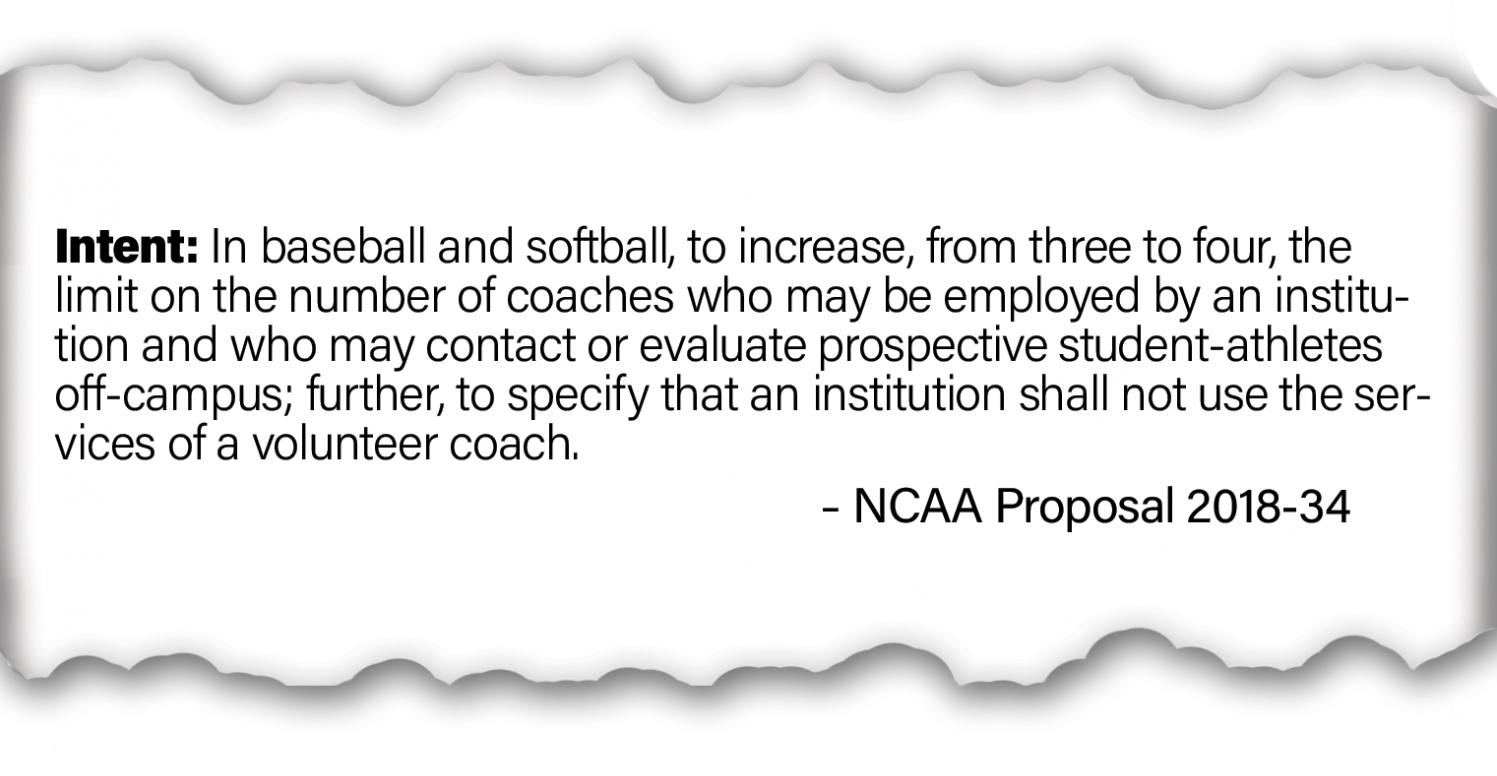

NCAA Proposal 2018-34, an amendment to be voted on this week at the NCAA Division I Council, would change the third assistant coach position in baseball and softball from a volunteer to full-time role at the Division I level. The measure has near-universal support from college baseball and softball coaches across the country, but its backing among administrators is more divided.

And when the votes are cast, the conference that may play the most important role in getting the proposal passed is the Big Ten.

NCAA Proposal 2018-34

Baseball and softball currently have the same coaching limitations. Both sports are allowed three countable coaches — paid staff members who provide instruction, assist in tactical decision-making and recruit off-campus. For most programs, like Northwestern’s two teams, that equates to one head coach and two assistant coaches.

NCAA Proposal 2018-34 — submitted by the SEC — would amend Bylaw 11.7 in the NCAA Division I Manual, changing the maximum number of full-time coaches allowed on baseball and softball staffs from three to four.

Craig Keilitz, the executive director of the American Baseball Coaches Association, and Joanna Lane, the director of education and program development for the National Fastpitch Coaches Association, said well over 90 percent of coaches support the change.

The idea has been floated around “off-and-on” throughout the three years Matt Boyer, the SEC’s assistant commissioner for compliance, has worked in the SEC office. But only recently did it reach formal discussions, he said, during the conference’s annual spring meeting in May 2018.

Those conversations led to the formal proposal the conference submitted to the NCAA in August. The Division I Council will vote on the amendment at their April meetings, which will take place Thursday and Friday.

Under the proposal, schools can decide how to handle the fourth countable coach. A school can pay an assistant coach as much or as little as it wants — and can even elect to not pay at all if it chooses. While the failure to mandate that institutions pay this position may make the amendment seem irrelevant, the proposal’s significance goes beyond the money.

Even if they were not paid, they would receive all the benefits paid assistant coaches do. It also places equal value on coaches’ well-being — along with that of student-athletes — and provide opportunities to up-and-coming coaches.

“It’s really not about how much they are going to get paid,” said Karen Weekly, NFCA president and co-head softball coach at Tennessee. “It’s just removing those restrictions so they’re treated under the rules the same way as the other coaches.”

Life of a volunteer

The basis of a volunteer’s pay comes from youth and prospect camps run by their school’s baseball or softball programs. Depending on the camps’ reputation and success, a volunteer might make a liveable wage.

But that’s only a select group. Not every school’s camp series makes enough for a volunteer assistant coach to earn a significant amount of money.

Bo Martino, who is the volunteer assistant coach at Stephen F. Austin, is part of the latter group. He said he works about 12-hour days — which include his job as a volunteer assistant coach, holding private lessons after practices and running tournaments during the offseason.

Martino said the proposal would be a “game changer” for his family. He has a son who recently turned 1, and because of the hours he spends working, Martino usually only spends time with him in the mornings. In addition to the benefits of having health insurance for his family, the chance to cut back on his other work would provide him the opportunity to spend valuable time with his wife and son.

“He’s walking, he’s going to start talking soon and if you are not home, you are going to miss a lot of those things that are milestones in your family’s life,” Martino said. “It’s just frustrating at times when you’re not missing (them) because of the actual job, you are missing (them) because you have to do things extra to make money to supplement an income.”

Martino said on a normal non-gameday in the spring, he works until 9 or 9:30 at night. Keilitz said many volunteer coaches are often treated the same as countable coaches by players, and pull 50-70 hour work weeks.

For John McCormack — the chair of the Div. I committee of the ABCA and the head baseball coach at Florida Atlantic — the lack of medical insurance provided to volunteer assistant coaches has led to perpetual nervousness about what could happen if he gets hurt on the job. The opportunity to get those health benefits, Skelley noted, would have a positive impact on the quality of life for young coaches.

Brett Schneider, currently in his second season as Florida Atlantic’s volunteer assistant coach, lives at his parents’ home and does not pay rent. However, McCormack said housing has been an issue in the past.

“Boca Raton, the rents are pretty pricey,” McCormack said. “So it’s always been a little bit of a tough thing for us to keep a volunteer because of that. Camp money only goes so far.”

Those challenges might not be universal, but for some, they are a barrier to entry for the position. For most people, being a volunteer assistant coach is a stepping stone to other jobs. But it can be a difficult path to follow without a safety net.

The hope is that by making this role full-time, people who would have faced barriers in making ends meet in the position will now be able to take on the job.

When Ray Tanner — the former head baseball coach and current athletic director at South Carolina — took over in Columbia, his first two volunteer assistants worked other morning jobs before heading to the baseball offices: one at a bagel shop working from 5 a.m. to noon, and the other as a high school teacher.

But once his volunteers earned enough from camps to pay their bills, Tanner said they focused all of their effort into coaching.

Current NU volunteer assistant coach Dillon Napoleon does not hold another job, and neither did Skelley. While Cats head coach Spencer Allen would have been supportive of Skelley’s choice to pick up extra work, he wanted to focus on his passion.

“If I got a random job in Evanston, it would have been time that I’m not in the office, and I’m not learning and getting better, being around the coaching staff and being around the players,” Skelley said. “I felt like, ‘How am I going to progress if I’m not here all the time?’”

Home and away

When head coaches look to hire a new assistant, McCormack said one question is always asked: “Can the applicant recruit?”

Recruiting is one of the most important parts of any coach’s job, so applicants need experience to make themselves competitive. There are two sides to recruiting, McCormack said: evaluating talent and selling players on the school. Learning how to do the latter well takes time. Yet, volunteer assistant coaches are prohibited from off-campus recruiting, and therefore, unable to develop this crucial skill.

“It’s hard because you have to develop your voice, if you will — the way you approach young people, the way you approach parents, how you lay out what the university has to offer them,” McCormack said. “It takes a little practice.”

The ability for a fourth coach to recruit would also benefit the rest of the coaching staff.

Off-campus recruiting means time away from players and families. An extra coach could more evenly distribute the recruiting burden to allow coaches more time on campus. From a player’s perspective, this means more time to build relationships with coaches and receive more focused instruction in offseason practices.

For softball, the meat of the recruiting is done in the fall, and sometimes multiple coaches might be off campus for those trips. NFCA executive director Carol Bruggeman said that stretch can be tough on players, and having an extra recruiter should increase access to coaches — both for on-field and off-field discussions.

“Let’s say you’re a college freshman,” Bruggeman said. “It’s late September your freshman year and the classes start to pile on…You may or may not be a little homesick. If you’re not a confident, well-versed young lady on campus resources and that sort of thing, you might be a little lost there for a while.”

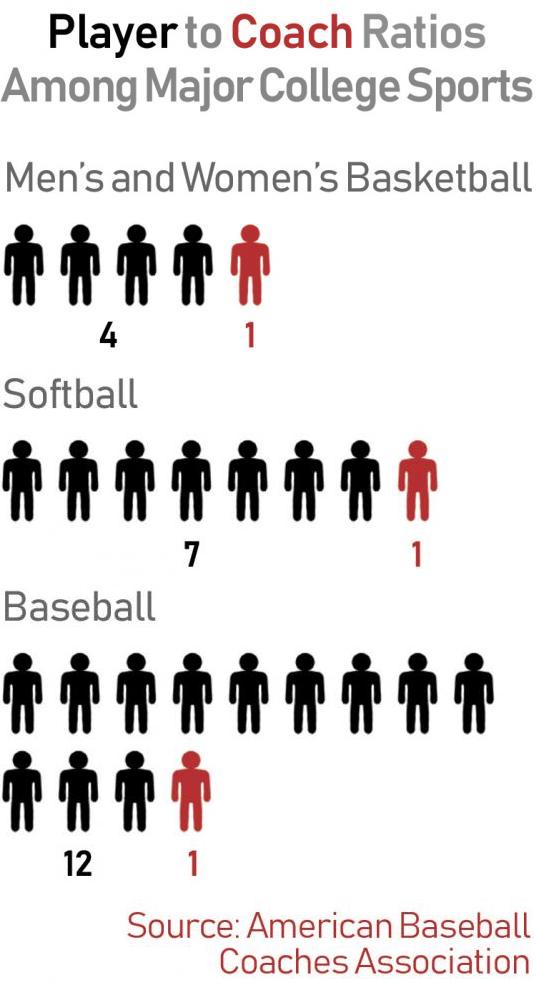

The player-to-coach ratio is a central part of the proposal. Baseball’s player-to-countable coach ratio is about 12-to-1 — the worst among nationally played college team sports, and one Boyer called “exceedingly high” and in need of change. No other sport is above 8-to-1.

Baseball players have many different skills to develop, and ideally would receive specialized training for their positions. But with such a high ratio, McCormack said coaches are forced to wear multiple hats and split their time among subsets of players.

“Don’t our athletes — baseball players — deserve the same thing everybody else is getting?” McCormack said. “We talk about student-athlete welfare a lot. We have 35 athletes, and it’s time that we get another paid coach to be on staff.”

Reasons for pause

While the proposal’s creators do not see downsides to the measure, administrators across the country — and even a few coaches — are more cautious.

Texas’ athletic director Chris Del Conte said he would “fully support” adding a third assistant coach for baseball, but felt there had not been enough discussion around the impacts to softball. So he voted no.

“The reason for my pause supporting this current legislation is because we haven’t vetted the need for softball and felt we should do so,” Del Conte tweeted last week.

But Lane said the way the proposal is written, Del Conte would not have to fund both sports — he could pay one and not the other.

“He doesn’t have to give softball (another paid) position,” Lane said. “Title IX does not require it. Title VII does not require it. If he and his athletic department look and think baseball needs to fill that void first, that’s OK.”

Some coaches reportedly worry about being put at a disadvantage if their fourth countable coach is not paid. These coaches — likely to be working at smaller programs — believe they could have their personnel poached more easily by bigger institutions. On the flipside, Martino said he believes this proposal will actually help small institutions by leveling the playing field.

Big Ten administrators are also reportedly concerned about the measure causing other sports’ coaches to want to add to their staffs. Skelley said he thinks administrators are looking to the future, adding that people outside of athletic departments might not be thinking about those ramifications.

“They probably don’t realize the trickle-down effect that (the proposal) could have on other sports,” Skelley said.

But finding money to fund the position in the first place remains a worry for some. Though a salary is not required, schools will still have to pay for the health benefits the coaches will receive, among other things.

Tanner emphasized that budget concerns should not factor into the vote. Those concerns affect him like any other athletic director, but Tanner said he feels the proposal’s benefits — including the ability to pay what one can — are more important.

“This is a student-athlete well-being issue,” Tanner said. “This is an opportunity to develop coaches. Don’t let the financial aspect of your budget weigh in whatsoever. If you take (the budget) off the table, why would you vote against it?”

The fact that the position doesn’t have to be paid is likely to play a key role in the votes of many smaller schools and conferences who would not have the funds to afford the position if they were forced to pay it.

Natalie Shock is the associate athletic director for compliance at Central Arkansas in the lower-tier Southland Conference. The school is in favor of the proposal, she said, but likely would not be if the fourth countable coach had to be paid.

“At our level, with our budget, is it going to be a paid position?” Shock said. “Probably not.”

The Big Ten influence

Many conferences nationally have not openly expressed opinions on NCAA Proposal 2018-34. The only official endorsement from a conference has been a March 1 public letter from SEC commissioner Greg Sankey.

However, the Big Ten has been in the spotlight following news of the conference’s likely vote against the proposal. On February 8, Aaron Fitt, a managing editor of D1Baseball.com, first tweeted the results of a straw poll conducted at a meeting of Big Ten athletic directors.

The vote was 13-1 against the proposal, and the lone “yes” vote reportedly came from Rutgers’ athletic director Patrick Hobbs.

The Daily emailed members of all 14 Big Ten athletic departments to ask if their respective athletic directors would be interviewed for this story. Only Iowa’s Gary Barta agreed. He told The Daily in an email there were mixed opinions in conference discussions.

“(We) have had more than one conversation on this topic in multiple meetings,” Barta wrote. “I don’t recall a ‘straw poll’ per se… and I don’t recall the sentiment being 13-1. I do recall there are differing opinions on the topic and people voiced where they stood at that time.”

Big Ten coaches were disappointed. In a column Fitt authored in support of the proposal, he cited four unnamed coaches in the conference who were angered by the results of the straw poll.

The news did not sit well with those outside the Big Ten. McCormack called the lack of support “disturbing” and Tanner felt it was “disappointing.”

Kyle Peterson — ESPN’s lead college baseball analyst and former two-time All-American pitcher at Stanford — said the results angered him, especially because of how much the quality of baseball in the Big Ten has risen recently.

“You look at the league from afar and go, ‘Man, they’re close,’” Peterson said. “Then you see that that is the feedback that their coaching staffs are getting from their administration — it was maddening. If I was a head coach at one of those programs, I would have been a little ticked too.”

Passing the proposal

The vote of a single conference might not seem particularly important. But the Big Ten is one of the most powerful conferences in the country, and that power is apparent in how the voting process works.

The Division I Council has 40 members, the majority of whom are conference representatives. Each of the 32 Division I conferences has one representative in the Council. Those 32 conferences are split into four different subdivisions: the Autonomy Conferences, Non-Autonomy Conferences, FCS Conferences and DI Conferences.

The Autonomy Conferences are the traditional “Power Five” conferences: the ACC, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12 and SEC. The Non-Autonomy Conferences is the collective known as the “Group of Five” for FBS college football purposes: the AAC, Conference USA, MAC, Mountain West and Sun Belt. FCS Conferences are ones that sponsor DI football, but do so at the lower FCS level — for example, The Ivy League. DI Conferences are those that do not sponsor football — most notably, the Big East.

The other eight slots go to a variety of different groups. The commissioners of the Autonomy Conferences, Non-Autonomy Conferences, FCS Conferences and DI Conferences each have their own representative, who account for four of the eight other slots. The Student-Athlete Advisory Committee has two representatives, while the Faculty Athletics Representatives Association and Division IA Faculty Athletics Representatives each have one representative.

While each representative gets one vote, the weight of each vote is not the same.

Representatives of the Autonomy Conferences — and their commissioner representative — have a weight power of four for their vote. Representatives from the Non-Autonomy Conferences and their commissioner representative have a weight of two attached to their vote.

With the extra power of the Autonomy Conferences, having those five conferences in alliance is critical. There are 64 total votes, and a simple majority is needed for a measure to pass. The potential loss of the Big Ten vote makes passing the measure more difficult than expected.

Graphic by Troy Closson/Daily Senior Staffer

This became even more apparent after Kendall Rogers, another managing editor of D1Baseball.com, broke the news April 10 that the Big 12 held a non-binding vote and ruled against supporting the proposal.

Baylor, Kansas, Kansas State and TCU were the only four schools to vote “yes.” On the “no” side were Texas and Texas Tech, which saw their baseball teams make the College World Series last year, and Oklahoma, which saw its softball team advance to the Women’s College World Series.

Keilitz said he was “really surprised” by the results and added that coaches in the conference were “extremely disappointed.”

The Big Ten’s potential influence on other Midwestern conferences makes McCormack nervous about what a “no” might mean. He said he could envision a scenario in which other conferences in the region vote against the proposal due to the Big Ten’s likely decision.

There is still a chance that the Big Ten supports the amendment. Barta, who is the Big Ten representative at the Council meeting, said April 4 he has not formed a “final opinion” on the proposal and that no official conference vote had been held.

Yet after the news of the Big 12 vote broke, Keilitz said he did not know whether the proposal was going to pass.

“I hate to put anything on it because there are so many other factors,” Keilitz said. “But every time one of the Power Fives doesn’t back it, it gets a little bit more difficult.”

Not going away

If the Division I Council announces later this week that the measure passed, it would be a win for both coaches’ associations. Coaching in college baseball and softball would be forever changed — in supporters’ minds, for the better. The proposal would take effect August 1.

But if the proposal fails, there is no clear plan for what happens next.

Boyer said the SEC has not spent much time discussing what would happen if the vote does not pass. It would be sent back to the drawing board, McCormack said, to create a version that can pass the next time it goes in front of the Division I Council.

One Big Ten coach told Fitt that if the proposal does not pass, and the Big Ten votes against it, other conferences will blame the Big Ten — and hold it against them in scheduling. Another told Fitt the same will happen in recruiting.

Though Tanner said he does not see that as a possibility, McCormack thinks all the conferences who vote against the measure will see some blame put on them.

There is only one thing that is certain.

“If it doesn’t go through, it’s not going to go away,” Peterson said. “That’s for sure.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @thepeterwarren